Khaemweset (also given as Khaemwaset, Khaemwise, Khaemuas, Setem Khaemwaset, c. 1281-c.1225 BCE) was the fourth son of Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) and his queen Isetnefret. He is the best known of Ramesses II's many children after the pharaoh Merenptah (1213-1203 BCE).

Khaemweset is regarded as the "Egyptologist Prince" and the "First Egyptologist" for his efforts in preserving ancient monuments, temples, and - most importantly - the names of those who had built them. Egypt's history was already ancient by the time of the New Kingdom (c.1570-1069 BCE) and many of the structures from the Old Kingdom (c.2613-2181 BCE) had fallen into disrepair. Khaemweset took it upon himself to restore these buildings and monuments and make sure that proper credit was given to those responsible for them. In doing so, he preserved Egypt's past while, at the same time, creating new monuments honoring events of his own time.

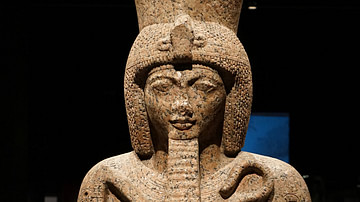

He was High Priest of Ptah at Memphis during his father's reign, presided over the burial of the Apis Bull, oversaw the construction of the Serapeum at Saqqara, and was named Crown Prince by Ramesses II. He died before he could succeed his father and the throne then went to his brother Merenptah. Although Merenptah's name is better known in the present day, not only because he succeeded Ramesses the Great but owing to his victory over the Sea Peoples, Khaemweset was better known in antiquity. Centuries after his death, Khaemweset was still remembered through the popular stories of Prince Setna Khamwas, the name a corruption of his title as priest, which were written from the Late Period (525-332 BCE) through the Roman Period (30 BCE-646 CE). Egyptologist William Kelly Simpson comments:

During Egypt's Late Period, the fourth son of the legendary Ramesses II became the central focus of one or more cycles of tales, somewhat reminiscent of the Arthurian cycles of medieval Western literature. In the Egyptian tales, Prince Kaemuas is designated by his priestly title Setna (older Setem), and it is his interest in ancient religious texts and magic that motivate the plot. This characterization has a firm basis in history, since the real Khaemuas served as Hight Priest or Setem of the Memphite god Ptah and justly may be termed the first known Egyptologist. (453)

Later generations honored him for his accomplishments in the same way they did Imhotep but stopped short of deifying him. He may have been denied divine status because of his habit of entering other people's tombs in his preservation efforts. Still, he was remembered as a great sage, magician, and adventurer and these qualities are all emphasized to varying degrees in the later stories written of him.

Youth & Priesthood

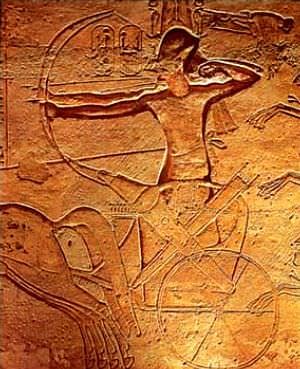

Khaemweset was born toward the end of the reign of his grandfather Seti I (1290-1279 BCE) and took part in military campaigns with his father when still a child. A relief from the temple at Beit-el-Wali depicts Khaemweset with his brother Amunhirwenemef accompanying Ramesses II (then a crown prince) on his campaign in Nubia. Reliefs such as this one demonstrate how Ramesses II regarded all his children equally, no matter who their mother was. Amunhirwenemef was the son of Ramesses II's best-loved wife Nefertari while Khaemweset's mother was Isetnefret, Ramesses II's second wife.

There are a number of reliefs and inscriptions showing Khaemweset's early life on the battlefield. At the famous Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE he is seen leading prisoners of war before the gods and, in others, he serves as his father's attendant. At the same time he was following Ramesses II on campaign he must have been attending school because, by the time he is 18 in c. 1263 BCE, he is a Sem-Priest of Ptah at Memphis. In order to hold this position, Khaemweset would have had to study to become a scribe and then receive education in becoming a priest. He would then have had to serve an apprenticeship under a higher ranking priest. If he actually did take part in military campaigns as shown he had to have been spending at least an equal amount of time in school.

He would also have been expected to devote himself to physical fitness as this was an important value of nobility in the New Kingdom. From the beginning of this era, the children of the pharaoh were encouraged in daily exercise. Males would need to be fit in order to succeed their father, preside over rituals and ceremonies, and lead troops into battle.

Females were also expected to remain in good physical condition to assume the position of God's Wife of Amun and be able to carry out the responsibilities of the title which included care of the god's statue, temple, and a leadership role in rituals and ceremonies. Khaemweset's youth, therefore, must have been quite active both intellectually and physically.

High Priest of Ptah & the Serapeum

In c. 1249 BCE, at around the age of 32, Khaemweset was already High Priest of Ptah at Memphis. In this position he was expected to care for the god's statue and temple, see to the upkeep of other temples and monuments, oversee daily rituals in Memphis, supervise the king's additions to the temple at Karnak, preside over the king's Heb-Sed Festival, and officiate at state funerals and those of the Apis bull.

The Apis bull was a sacred animal who was recognized, based upon certain markings, as the incarnation of the god Ptah himself. The bull was kept in the temple precinct at Memphis and, when he died in a ritual slaying, was given the highest honors and treated with the utmost respect and care in embalming. While the bull was being prepared for burial, a search was initiated for its replacement and, once found, Khaemweset would have had the final say in whether the bull was truly Ptah incarnate.

Once the new bull was installed at the temple, or as the search was still in progress, the mummified corpse of the old bull would be transported from Memphis along the Sacred Way to the necropolis at Saqqara. There he would be buried in a crypt with full honors. Previously, bulls were buried in their own crypts but Khaemweset seems to have felt this was inadequate for honoring the former home of the soul of the god.

He, therefore, had a large underground crypt created which would house all of the Apis bulls, each in their own granite sarcophagus, so that people could more easily visit to bring food and drink offerings. Khaemweset's Serapeum at Saqqara provided an elaborate tomb for the bulls which was orchestrated so well that it remains intact in the present day.

This very popular tourist attraction continues to mystify scholars and fringe theorists regarding how the immense granite sarcophagi, each of which weighs between 70-100 tons, were placed in their positions and what their purpose was. Although much of this matter is made by fringe theorists in various documentaries and articles, the answer is simply that the Egyptians made expert use of the technology they had - which was far more impressive than most of these writers and producers give credit for - and that the sarcophagi were constructed to house the remains of the Apis bulls.

Claims that no culture would have expended so much time and energy to bury an animal are clearly ignorant of Egyptian culture and religious beliefs. Khaemweset did not commission the Serapeum to "bury an animal" but as the eternal home for the body which once held a divine and immortal soul. In the same way that a human was embalmed, mummified, and buried in the expectation of eternal life, so were animals - everyday pets like dogs, cats, baboons, gazelles, even fish - but the Apis bull, as a god incarnate, would have been given even higher honors.

The First Egyptologist

Khaemweset would have traveled with his father around the country and would have seen, first hand, the monuments of the nation's past as he grew up. Although many of these were regularly cared for by the priests, many others had been neglected. As High Priest, Khaemweset was responsible for maintaining these structures and would have had access to the extensive historical records housed in the temple at Memphis.

The major temples of Egypt all had a section known as the Per-Ankh (House of Life) which was part scriptorium, writing center, classroom, and library. Khaemweset used these records to identify ancient monuments which had fallen into disrepair and then went out into the field to restore them. Scholar Sherine el-Menshawy, writing on this topic, quotes the Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen's obeservations on Khaemweset:

He was no doubt impressed by the superb workmanship of the splendid monuments of a thousand years before - and perhaps also depressed by their state of neglect, mounded up in drifts of sand, temples fallen into ruin. Deeply affected by all that he had seen, Khaemweset resolved to clear these glories of antiquity of the encumbering sand, tidy the temples, and renew the memory (and perhaps the cults) of the ancient kings. (17)

Khaemweset decided to uniformly restore and record these monuments, placing new inscriptions on them which would tell future generations who had built them, for what purpose, who had restored them, and under whose reign. These inscriptions vary from monument to monument but all include the information Khaemweset thought essential. In restoring the mastaba tomb of Shepsekaf (2503-2498 BCE), the last king of the 4th Dynasty, at Saqqara, Khaemweset had the following inscribed:

His Majesty instructed the High Priest of Ptah and Setem, Khaemwise, to inscribe the cartouche of king Shepsekaf, since his name could not be found on the face of his pyramid, inasmuch as the Setem Khaemwise loved to restore the monuments of the kings, making firm again what had fallen into ruin. (Ray, 87)

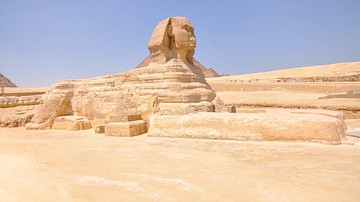

Khaemweset restored monuments from Saqqara to Giza including statuary which was found out of place. Among the best known of his efforts is his restoration of the statue of Prince Kaweb, son of the king who built the Great Pyramid, Khufu (2589-2566 BCE). Kaweb's statue had fallen into a shaft near a well and Khaemweset had it retrieved and set in a place of honor. He then had the following inscribed upon it:

It was the High Priest and Prince Khaemwise who delighted in this statue of the king's son Kawab, which he discovered in the fill of a shaft in the area of the well of his father Khufu. He acted so as to place it in the favour of the gods, among the glorious spirits of the chapel of the necropolis because he loved the noble ones who dwelt in antiquity before him, and the excellence of everything they made, in very truth, a million times. (Ray, 87-88)

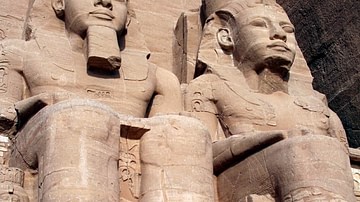

He not only restored this statue but the whole of the site at Giza. It is Khaemweset, in fact, who brought Giza back to life after centuries of neglect. Giza had been the royal necropolis of the Old Kingdom but since the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) the necropolis at Thebes had been used predominantly. By the time of Khaemweset, the pyramids and temples at Giza were already over one thousand years old and, since the site was full, no one was buried there anymore. In restoring the site and renewing the funerary cults of the kings, Khaemweset preserved what is easily the most famous and most often visited site in Egypt in the present day.

Criticism & Accomplishments

He is also responsible for ensuring that the name of his father would be remembered. Ramesses II is the best documented ruler of the New Kingdom and probably the best known in Egypt's history for his mistaken identification with the nameless pharaoh in the biblical Book of Exodus. Ramesses II is not the fictional pharaoh in that account, nor was any other pharaoh of Egypt, but his name was already famous enough to have suggested itself to early interpretations of the story.

This fame was due not only to his legendary reign but to the many inscriptions he left behind on monuments. While a number of these were original constructions, many were older structures which Khaemweset had his father's name inscribed on. It is for this reason that there is virtually no ancient site in Egypt which does not mention Ramesses II.

Critics of Khaemweset's work have suggested that he did not so much preserve ancient monuments as use them for his father's - and his own - enduring fame. Egyptologist Marc van de Mieroop comments on this:

Khaemwaset is sometimes described as an early archaeologist or the "first Egyptologist" but some scholars think that he used the massive structures as stone quarries for his father's building projects and left the inscriptions to ensure that the original owners remained known. (232)

There is no doubt that Khaemweset left a record of his efforts and the name of his father at the various sites but the claim that he purposefully used ancient monuments as quarries seems unlikely. It is certainly possible, however, that some of these monuments and temples may have been in such a state of ruin that they could not be restored and so were dismantled and re-used for new projects.

Khaemweset's great accomplishment was in restoration and preservation, not recycling, of the great monuments of the past. His efforts were rewarded during his lifetime as he was able to occupy himself in pursuing what he loved and was acknowledged for it. He died around the age of 56, years before his father, and was buried either at Saqqara or Giza. A ruined tomb discovered in pieces at Saqqara in 1993 CE has Khaemweset's name engraved on the blocks but the architectural style dates it to the Old Kingdom. It is entirely possible, however, that Khaemweset would have had his tomb purposefully constructed in the archaic style of the buildings he had spent most of his life restoring.

Over a thousand years after his death he would be honored and remembered in the Prince Setna stories which, though fictional, draw closely on Khaemweset's personality. He was known to be inquisitive and resourceful and had no fear of entering other people's tombs or any spirits which he might meet there or who might follow him home. Van de Mieroop writes, "It seems that later Egyptians admired Khaemwaset because he was able to read old inscriptions but, at the same time, thought him reckless as he entered tombs" (232).

In the best known tale, The Romance of Prince Setna and the Mummies (also known as Setna I), he encounters a family of ghosts in a tomb, steals a magic book, meets a beautiful woman who is possibly Bastet, and finds himself in the end naked in the street as a punishment for his rash actions. While none of these things might have happened to Khaemweset, the character of Setna exhibits the same deep regard for the past, knowledge of magic, and the same recklessness, as the famous prince was known for.

His abilities to understand old texts and restore ancient monuments made him a legend as a sage and magician and this reputation was only enlarged upon by later generations. The archaeologists who first began professionally excavating Egyptian sites in the 19th century CE owe the existence of their records, and in many cases the structures themselves, to the efforts of the prince and high priest Khaemweset.