The Kikuyu people (aka Gikuyu or Agikuyu) are a Bantu-speaking people who occupied territory in what is today central Kenya in East Africa from the 17th century onwards. They established themselves primarily as agriculturalists around Mount Kenya and the Highlands. The Kikuyu thrived and were able to use their foodstuff surplus to trade with neighbours such as the Maasai people.

Although for much of their history the Kikuyu did not form any centralised political institutions, they did eventually become the driving force of Kenyan nationalism and the anti-colonial movement in the mid-20th century, particularly the Mau Mau uprising. Today, the Kikuyu make up some 20% of the population of Kenya where they are the largest ethnic group.

Origins & Territory

The forerunners of the Kikuyu and several other groups in East Africa were the Thagicu, a Bantu-speaking group who from the late 11th century migrated to the region from central Africa. The Thagicu began to clear the forests around the southern slopes of Mount. Kenya to create land suitable for agriculture. Consequently, as in other regions, the Bantu-speakers spread their knowledge of iron-smelting, pottery-making, and farming skills with indigenous forager and nomadic tribes. Archaeological evidence of iron-smelting and new types of pottery in the area has been radiocarbon dated to the 12th century or even the 11th century.

There were also migrations of people to the area from the east coast and northeast Africa (a movement which features in the Kikuyus' own oral traditions), creating a melting pot of cultural and technological exchange that led to thriving communities able to produce a surplus of foodstuffs. By the 17th century, this mix of peoples had evolved into two major and distinct ethnic groups: the Meru and the Kikuyu who spoke a Bantu-derived language of that name. The name Kikuyu is from the Swahili language whereas the people themselves use the name Gikuyu (pron.: geekoyo).

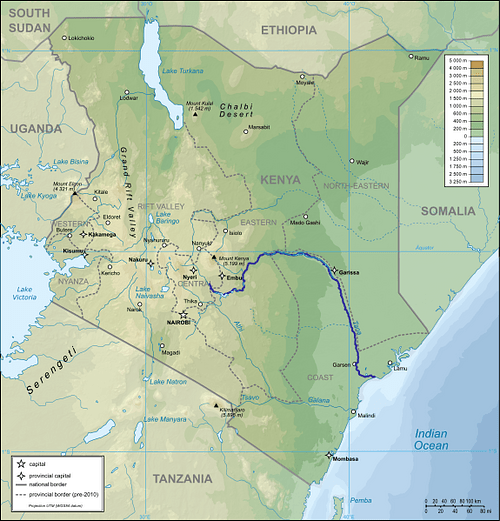

The Kikuyu, moving slowly southwards, came to occupy the territory in what is today central Kenya, south of the River Tana and between the coast and Lake Victoria to the west. This area is sometimes called Kikuyuland. Their southern neighbours were the Maasai and to the north of them were the Somalis. Trade routes largely passed to the south of the Kikuyu area from Pangani on the coast to northern and southern Lake Victoria. Kikuyu traditions do record a long-standing trade with the Akamba people to the south and the closer Maasai. The former exchanged animal skins and uki (a type of beer), while the latter offered cattle, milk, skins, and leather cloaks for staple foodstuffs and manufactured goods. Illustrative of the peaceful relations between these various peoples is the fact that the Akamba often exchanged their labour for goods each harvest time.

Agriculture

The Kikuyu people cultivated millet, above all, but also beans, peas, sorghum, yams, and ndulu (a green vegetable traded in quantity with the Akamba). Some crops like maize and sweet potatoes had been introduced to the region via the Portuguese in the 17th century. Farming methods included the use of irrigation and terracing but were not universally applied by all Kikuyu groups. Tools included hoes, axes, machetes, and digging sticks. Livestock was kept as a source of milk, meat, and leather for clothing. Unlike say the Maasai, animal husbandry was very much secondary to agriculture and so the ownership of cattle, in particular, was a sign of status in Kikuyu society. Not all Kikuyu groups were predominantly agriculturalists, some in the south were pastoralists like the Maasai, or at least semi-pastoralists, while the Athi Kikuyu thrived on hunting and collecting honey and beeswax. Today’s Kikuyu farmers largely concentrate on coffee, maize, and fruit.

Social Structure

In the 17-19th century, the typical Kikuyu home was a homestead organised around a single extended family with males taking several wives. Each wife lived in their own hut. The buildings of the homestead were protected by an encircling stockade of wood or bush. Buildings were made from mud, stone, and vegetable matter, and there was a tradition that a Kikuyu hut had to be built within one day, which meant a good deal of planning, preparation, and communal effort was required. The reason for such a short deadline was because the Kikuyu believed that an unfinished house if left overnight would attract unwanted spirits who might take possession of it.

The Kikuyu had no tribal chiefs, but the population as a whole was divided into several clans and subclans (today there are nine such clan groups). Extended family groups, or mbari, within these clans were headed by a number of senior, related males who were ranked according to their age group. Inheritance went through the male line. Each mbari could be composed of anywhere from 30 to over 300 people. Even though the Kikuyu have abandoned the individual homestead for village life, the mbari remains an important social unit. The importance of family ties is also reflected in the belief that the spirits of ancestors are present and available to help the living. Grouping people into age ranges was very important for social status, as were rites of passage for adolescents, which included male and female circumcision.

The predominance of family units and the physical barriers between groups - many occupied individual mountain ridges - meant that the Kikuyu people had no centralised government, bureaucracy, or even perhaps a sense of belonging to a particular wider ethnic group. This situation of politically and culturally isolated communities was heightened by the strong localised traditions such as oral histories of specific family groups. However, as the UNESCO General History of Africa notes:

Decentralisation…did not mean disorganization or lack of political and social cohesion. These decentralized societies had family, village and district councils made up of elders. Members of each family, clan and district were united by relationships which defined and governed the actions of individuals and established mutual obligations and rights. (Vol V, 414)

Religious Practices

As noted, ancestor worship was a key part of the Kikuyu pre-colonial religious practices. Believed to be capable of helping the living, ancestors were offered certain sacrifices and rituals, called koruta magongona. It was believed that ancestors lived below the ground but they could appear amongst the living when seeking to communicate with them; illness was considered a typical form of such communication. The Kikuyu gods also benefitted from such rituals, the supreme god being Ngai, while others may have been envisaged as supernatural beings without names or form. Ngai was thought to dwell on Mount Kenya and so all rituals were directed at that mountain. A third group of spirits is those who meant to do harm to the living. Religious ceremonies, which aimed to please all of these supernatural beings and call upon their assistance in daily life, included the offering of food and drink, animal sacrifices (sheep and goats), dancing, the temporary observation of taboos, and ritual sexual intercourse. Rituals were not carried out by priests as such but were the reserved domain of community elders, often performed under a particular tree, which was considered sacred.

Foreign Invasions & Conflicts

Despite the long-standing and peaceful cross-regional trade relations, the 19th century witnessed a generally more violent East Africa. There were invasions from the Arab and coastal traders, as well as forces from European states. The Kikuyu were as militaristic as any other tribal peoples in the region in a period where the introduction of firearms meant that only a small band of warriors was required to wreak havoc on its neighbours. Trade caravans travelling to and from the coast were a particular target, as were the resources of poorly defended villages which could also be a source of slaves, valuable for trading. The Kikuyu raiding parties were known as thabari, which derived from the Swahili word safari, meaning a journey or caravan. The Kikuyu seem not to have been interested in cultivating long-term peaceful commercial relations with Arab and Swahili Coast traders over the duration of the 19th century. This was perhaps a symptom of their lack of a centralised political system, which might have allowed the Kikuyu as a whole to take such opportunities or better face the threat from Britain, eager to establish a colony in the region from the late 19th century. The British East Africa Protectorate was established in 1895 and the colony of Kenya in 1920.

The Kikuyu & Modern Kenya

The Kikuyu Central Association (KCA) was established in 1924, and it championed a nationalist agenda in Kenya, which aimed at redressing colonial grievances, taking a firm stance against European ownership of land and certain aspects of missionary work in the country. There were also severe practical problems caused by an increase in population density in the Kikuyu highlands where the soil was no longer able to bear the intensive agriculture required. The KCA brought the Kikuyu to the forefront of African nationalism in Kenya, but the organisation was banned by the British Governemnt during the Second World War (1939-1945). In 1944, the KCA’s successor was created, the Kenyan African Union (KAU). One of the founders of the KCA was Jomo Kenyatta (1891-1978), and he continued to take a prominent role in post-war Kenyan politics, being elected as president of the KAU in 1947.

The so-called ‘Mau Mau’ uprising (a British term of disputed significance) occurred between 1952 and 1960. This was a violent episode in the country’s history, which saw the Kikuyu again take the leadership, but this time in a much more militant, anti-colonial guerrilla action against both white settlers and Kikuyu who were considered collaborators with the colonial system. A particular policy aim was the removal of white landowners from the former Kikuyu territory known as the ‘White Highlands’, a particularly fertile area which the Kikuyu had been excluded from farming by the colonial government. Kenyatta was tried and imprisoned for his role in the uprising, although the evidence used against him was later found to be perjured. The Mau Mau uprising had resulted in the deaths of 32 white civilians and 13,000 Africans. Some 80,000 Kikuyu had been placed in detention camps. Released in 1961, Kenyatta was elected the first Prime Minister of an independent Kenya in 1963 and then made President in 1964 when the country became a republic. After this tumultuous post-war decade, Kenya was then surprisingly peaceful and gained significant economic success, particularly from exports such as tea and coffee and from tourism to its national parks.