The king’s evil (from the Latin morbus regius meaning royal sickness), more commonly known as scrofula or medically tuberculous lymphadenitis, was a skin disease believed to be cured by the touch of the monarch as part of their inherited divine powers. The idea that the royal touch, a simple laying of hands by the monarch on a sufferer, could cure the infection persisted for 1,200 years down through the 18th century. The cause of the infection was not known until the late 19th century. Historically, the illness was often referred to as consumption, phthisis, scrofula, the "king's touch", the "white plague", and the "captain of all these men of death". In 1839, Johann Lukas Schönlein, a German physician, coined the term "tuberculosis" as a generic term for all the manifestations of tuberculosis since the tubercle was the anatomical basis of the disease.

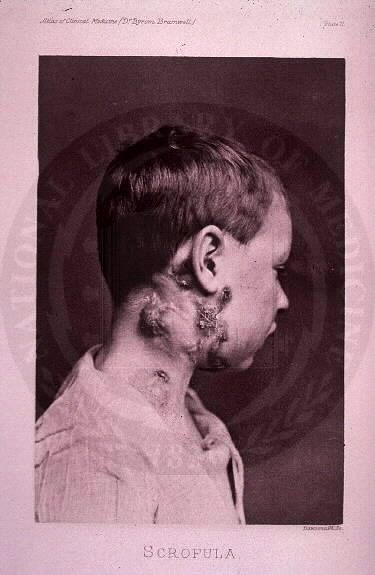

Scrofula (Tuberculosis)

Keith Manchester, in Tuberculosis and Leprosy in Antiquity: An Interpretation, provides a clear history of the role that tuberculosis has played in human history. Manchester begins by identifying tuberculosis (TB) as a chronic bacterial disease from the genus mycobacterium and the species Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Humans are affected by one of two forms: human or bovine. The human type of TB usually enters through the lungs after human-to-human contact with another person’s affected breath. This form of TB is especially virulent in dense, urban areas. The bovine form begins in the gut and is usually acquired by consuming infected milk or eating infected meat. The bovine form is most likely man’s earliest encounter with TB because it was present in the first domesticated cattle herds or infected any of the animal herds hunted for meat.

Scientists have dated the earliest cases of TB from a mummy of the 21st Dynasty of the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (1070-946 BCE). Europe probably experienced the first outbreaks of TB in the post-Roman period and in particular in Britain sometime in the 3rd to 5th centuries CE. The spread of the disease in Europe and Britain resulted from the growing number of towns and cities with higher population densities and the expansion of trade. Manchester also argues that the rates of TB likely decreased during the outbreak of bubonic plague, or the Black Death, in the 1340s as the population died off while the lower living standards and general poorer state of health contributed to spreading TB wider. In the 15th century, expanding cattle herds led to the emergence of bovine-type TB. Tuberculosis was also known to spread during the medieval period as people lived in the same houses with their animals leading to increased human-to-animal contact, thus increasing the spread of bovine TB. The social stage was set for people infected by TB and lacking the required medical expertise to turn to a superstitious remedy, the king’s touch.

Symptoms

The bacterium, tuberculosis lymphadenitis, entered a person by breathing contaminated air. Scrofula exhibited multiple symptoms in the sufferer. The illness caused chills, sweats, and fevers. Due to the swelling of the lymph nodes and bones, skin infections and ulcerated sores appeared on the neck, head, and face resulting in a "pig-like" appearance (first identified by Aristotle). Once infected with the bacterium, the sores grew slowly and sometimes remained with the patient for months or even years. Those lesions were proof positive, as some believed, of sin. In time, scrofula would present in three forms: acute, chronic, and fatal. In the acute stage, the illness's symptoms would emerge, then disappear, and then re-emerge. The chronic stage was marked by the constant long-term presence of symptoms and sores. The fatal stage led to death.

Treatment

The appearance of scrofula was often associated with gluttony, especially in children. One of the first treatments to be tried was to change a person’s diet by restricting any foods that emitted an odor like garlic, onions, and wine. It was also thought that behavioral changes would reduce or cure the problem so limiting or reducing the amount of shouting, anger, or worry was sometimes prescribed.

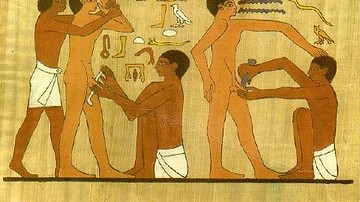

Medically, various approaches were employed to counteract the disease. The ancient Egyptians treated the illness with surgery and various dressings. Hippocrates recommended rest, pray, drinking milk, diet, and the avoidance of extreme weather. The Chinese tried acupuncture. And Anglo-Saxons used herbs, leeches, and amulets. If those remedies proved unsuccessful, doctors engaged in surgery. The procedure involved cutting into the outer layer of the skin, scraping away the flesh, and pulling on the scrofula pustule. If too much bleeding occurred, then the procedure would be stretched over multiple days extracting only a few pustulates per day. If all of those surgical or non-surgical attempts failed, then the patient would be sent to visit the king.

Ritual

In imitation of Christ’s healing powers, English and French kings engaged in a ritual known as “touching” in order to cure sufferers of scrofula. The ritual sprung from the practice of churchmen who practiced healing by touch. The royal touch ritual dates back to the time of Clovis of France in 496, and its earliest appearance in England occurred during the reign of Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066). The practice became formalized during the kingships of Louis IX of France (r. 1226-1270) and Edward II of England (r. 1327-1377), respectively.

The process of the ritual is best described in a first-hand account by John Evelyn (1620-1706), an English writer, gardener, and diarist in his diary dated 6 July 1660. A description of the ritual also appears in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Act IV, scene III:

…there are a crew of wretched souls

That stay his cure: their malady convinces

The great assay of art; but at his touch—

Such sanctity hath heaven given his hand—…

'Tis call'd the evil:

A most miraculous work in this good king;

Which often, since my here-remain in England,

I have seen him do. How he solicits heaven,

Himself best knows: but strangely-visited people,

All swoln and ulcerous, pitiful to the eye,

The mere despair of surgery, he cures,

Hanging a golden stamp about their necks,

Put on with holy prayers: and 'tis spoken,

To the succeeding royalty he leaves

The healing benediction.

The sick individual was brought before the king and then kneeled in front of the monarch. The king touched the face and cheeks of the afflicted person while a chaplain announced that "He put his hand upon them, and he healed them." The chaplain’s words referred to a passage in the Gospel of Mark 16:18 in which Jesus, speaking to his disciples after the resurrection, suggests that the disciples will have healing powers. Many people believed that the disease was brought on by sin, so prayers were central to the ceremony. The sin of the disease was not limited to the afflicted individual; it was also a result of the collective sins of a family, a village, town, or kingdom.

Along with prayers was also the need for redemption; both were necessary for invoking God’s healing powers. The king, then, acted in place of God. The whole of the public ritual produced an increase in popularity for the king, especially if people believed that the king’s touch was successful, while it also allowed the monarch to claim divine powers further increasing the legitimacy of the throne. After the ceremony, the newly touched afflicted person would receive a gold coin from the king which was referred to as a "touch piece" (in England the same coin was referred to as an angel). The cure could also be administered by sprinkling water which had been used to rinse the hands of the king on the ill.

The ritual became even more popular under the reign of James VI of Scotland (also known as James I of England, r. 1603-1625) who stopped the tradition of making the sign of the cross over the sores as it was too Catholic, thus making the ceremony more Protestant. The practice of the ritual reached its height under Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685) who was its greatest practitioner. Charles often touched nearly 6,000 people per year, while throughout the whole of his reign, it is reported that he engaged 96,000 in the ceremony. William of Orange (r. 1689-1702) ended the practice as he simply did not believe that the ritual worked, however, it was briefly revived during Queen Anne's reign (r. 1702-1714 CE).

Consequences

The king's touch, of course, cured no one. Kings did not possess divine healing powers. Nevertheless, the public thought that the king could perform such a cure. Any person who was touched by the king was allowed to return to normal life in society. That action most likely resulted in helping to spread the disease to others who had not been infected. The king’s powers went beyond simply affecting a remedy to the disease, and the thousands of rituals performed also helped to cure the nation’s sins and make the whole of society more godly.

There is simply no way to know how many people have died from tuberculosis over the millennium. Dating back as far as 8,000 BCE, millions of people have perished. It has been suggested that TB has killed more people than any other microbe. In 1882, a German doctor, Robert Koch, discovered the bacteria that caused tuberculosis. The development of the X-ray, in 1895 by Wilhelm Konrad von Röntgen a German engineer and physicist, greatly aided medicine’s ability to detect TB in a person’s lungs. The first vaccine for the treatment of TB was developed in 1908 by two French bacteriologists, Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin. By 1945, a whole range of antibiotics, especially streptomycin, became available for treating people suffering from TB. Within the last decade, a multi-drug resistant form of tuberculosis (MDR-TB) has emerged, causing 500,000 cases worldwide according to the World Health Organization.