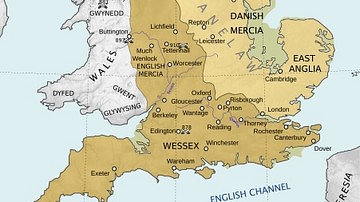

Egbert of Wessex (l. c. 770-839 CE, r. 802-839 CE; also given as Ecgberht, Ecbert) was the most powerful and influential king of Wessex prior to the reign of Alfred the Great (r. 871-899 CE). Egbert came to the throne at a time when the neighboring Kingdom of Mercia had dominated Wessex and controlled the sitting king Beorhtric (786-802 CE) through an alliance sealed by marriage. Egbert seems to have taken time to assemble his military and resources and then met the Mercian armies and defeated them at the Battle of Ellandun in 825 CE. Afterwards, he swiftly took Mercian territory, installed his son Aethelwulf (r. 839-858 CE) as sub-king, and neutralized Mercian aggression. Egbert was the first king of Wessex to completely subdue Mercia and the stability he provided allowed for further development of the kingdom as well as the resources to withstand the Viking raids. At his death, he was so powerful that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles refer to him as Ruler of Britain, not just King of Wessex.

King Egbert is featured in the TV series Vikings (where he is called Ecbert, played by English actor Linus Roache) and is depicted as mercenary, manipulative, and self-serving for the most part, though still a cultured, intelligent, and articulate monarch. This characterization is possibly drawn from the historical Egbert's initiatives in consolidating his kingdom but is largely fictionalized and without any detailed historical basis.

Early Life & Rise to Power

Egbert was possibly born in Kent, “the son of the short-lived ruler of that kingdom called Eahlmund r. 784-785 CE” (Collins,196). His Kentish origin is supported by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles but has been called into question by recent scholarship claiming he was originally from Wessex. Nothing is known of his youth beyond his possible relation to Eahlmund and the claim that he could trace his ancestry back to Cerdic (r. 519-540 CE), the founder and first king of Wessex.

This claim is made by later genealogies, however, which were written by the scribes of Wessex after Egbert had already established himself as a powerful king and so may not be reliable. Linking Egbert to Cerdic would have enhanced his status and it was a fairly common practice for the scribes of kings to attribute to their liege impressive pedigrees even if they could not be proven. Even so, it is possible that Egbert descended from Cerdic and a West Saxon noble who was also connected to the Kingdom of Kent would not have been unusual.

It is probable that Egbert came from Kent, however, and was descended from the king Egbert of Kent (r. 664-673 CE) or, almost certainly, Egbert II (r.765-c.779 CE) the father of Eahlmund. If one assumes a Kentish origin, then he would have grown up during the period of Mercian supremacy of the kingdom. King Cuthred of Wessex (r. 740-756 CE) had defeated Mercia and elevated Wessex (and so Kent) during his reign but these gains were lost during the reigns of his successors Sigeberht (r. 756-757 CE) and Cynewulf (r. 757-786 CE). By the time Egbert was born in c. 770 CE, Mercia was the dominant power and was ruling Kent through client-kings (as they had, on and off, from as early as 664 CE).

Kent defeated Mercia in battle c. 776 CE under the reign of Egbert II and maintained its independence through the reign of Eahlmund but King Offa of Mercia (r. 757-796 CE) reasserted his power in 785 CE and again took control of the kingdom. In 786 CE, Cynewulf of Wessex died and the nobleman Beorhtric (r. 786-802 CE) was in line to assume the throne but was challenged by Egbert – who seemingly comes out of nowhere to assert his right to rule Wessex (thus arguing for Wessex nobility as his origin). Beorhtric was supported by Offa, however, who sealed a contract with Wessex by marrying his daughter Eadburh to Beorhtric; Egbert was driven into exile and fled to Francia.

At this time, Francia was a united empire under the rule of Charlemagne (King of the Franks 768-814 CE, Holy Roman Emperor 800-814 CE) who protected the young exile. Charlemagne seems to have disliked Offa as it is said he was outraged when Offa proposed an alliance which would be sealed by the marriage of Offa's son Ecgfrith (r. 796 CE) to one of Charlemagne's daughters, Bertha. Even so, Charlemagne did nothing at this time to upset Offa's plans in Wessex – possibly because Beorhtric had a legitimate claim to the throne which superseded Egbert's.

Offa died in 796 CE and Ecgfrith, his successor, soon after. The nobleman Cenwulf of Mercia (r. 798-821 CE) took the throne (probably after assassinating Ecgfrith) and continued Offa's policies regarding Wessex and its king. He maintained Mercian superiority in the region and Wessex operated as more or less his puppet kingdom. Egbert remained in exile in Francia at this time but, when Beorhtric died in 802 CE, Charlemagne seems to have supported Egbert's bid for power and he became king of Wessex.

Early Reign & The Battle of Ellandun

Little is known of the first 20 years of Egbert's reign. He seems to have reasserted Wessex's independence from Mercia but there are no records of how nor of military campaigns between the two kingdoms. Instead, in c 815 CE, Egbert led his armies west to conquer the region of Dumnonia (modern Cornwall) on his border. These campaigns were probably encouraged by Dumnonia's lucrative ports and trade contacts, skill in metalworking, and other resources Egbert would require to enlarge and equip an army.

Wessex had been under Mercia's control since 785 CE and there are no records of any military activity under the reign of Beorhtric. Although there are also no records of any military build-up in Wessex in Egbert's early reign, this must have been where he concentrated his efforts because, between c. 815-820 CE, he could effectively campaign in Dumnonia and in 825 CE he was able to mount an effective offense against Mercia itself.

Cenwulf of Mercia died in 821 CE and was succeeded by his brother Ceolwulf I (r. 821-823 CE) who was then deposed by the nobleman Beornwulf (r. 823-826 CE) while Egbert was gathering his forces which would win the Battle of Ellandun and shatter Mercian supremacy. The entry in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles for 825 CE reads:

Egbert, king of the West-Saxons, and Beornwulf, king of Mercia, fought a battle at Wilton [modern day Wiltshire], in which Egbert gained the victory, but there was great slaughter on both sides. Then sent he his son, Aethelwulf into Kent with a large detachment from the main body of the army, accompanied by his bishop, Elstan, and his alderman, Wulfherd; who drove Baldred, the king, northward over the Thames. Whereupon the men of Kent submitted to him; as did also the inhabitants of Surrey and Sussex, and Essex.

Details of the Battle of Ellandun have been lost, or were never recorded, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles are notorious for brief and tantalizing entries so there is no account of how Egbert mobilized or led his army. However he conducted the campaign, it was successful. Even though Mercia would later assert itself and reclaim some of its lands and independence, it would never be the power it had been before Ellandun. The Chronicles note a string of victories following Ellandun and in 827 CE states: “Egbert, in the course of the same year, conquered the Mercian kingdom, and all that is south of the Humber, being the eighth king who was sovereign of all the British dominions.”

Supremacy of Wessex

Although the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles claim 827 CE as the year of Wessex's complete supremacy, this date has been challenged by archeological and literary evidence. Mercia had lost territory, power, and prestige but was still ruled by Mercian kings. Beornwulf survived the Battle of Ellandun but was killed fighting against the East Angles in 826 CE and was succeeded by Ludeca (r. 826-827 CE) who died in battle the following year trying to complete Beornwulf's campaign to suppress East Anglia's revolt. Wiglaf (r. 827-829, 830-839 CE) then took the throne and did his best to retain some form of Mercian autonomy from Wessex.

The entry in the Chronicles for 825 CE stating that Egbert sent Aethelwulf to Kent to depose Baldred is considered off by a few months or a year and that probably happened in 826 CE. Baldred was the client-king of Kent under Beornwulf and his loss would have been significant to Mercia. Following the outing of Baldred, Egbert claimed kingship of Kent as overlord to Aethelwulf who served as his client king there as well as over Essex, Sussex, and Surrey.

Between 825-829 CE, Egbert continued expanding his realm at Mercia's expense. In 828 CE he conquered North-Wales and in 829 CE he accepted the submission of the Kingdom of Northumbria and, at the same time, drove Wiglaf from his throne and took direct control of Mercia. By c. 830 CE, he was the most powerful king in the land and Wessex controlled resources and trade from the south of Britain all the way through to the north.

Loss of Mercia & the Viking Raids

Although Egbert would retain control of the north, his grasp on Mercia slipped in 830 CE when Wiglaf returned from exile and regained his throne. Many different theories have been suggested for the cause of Mercia's revival but the most probable is loss of support for Wessex from the Carolingian Empire. The empire of the Franks was secure under the reign of Charlemagne but, when he died in 814 CE, he was succeeded by his son Louis the Pious (r. 814-840 CE) who had greater difficulty managing his enormous realm.

It was not just the magnitude of the empire that posed a challenge, however, but the loss of the commanding presence of Charlemagne. Throughout his reign, Charlemagne had engaged almost incessantly in successful military campaigns. To the Scandinavians, Saxons, and Slavs, he seemed invincible on the battlefield and few were willing to contest with him even before the Saxon Wars (722-804 CE) in which Charlemagne conquered Saxony and slaughtered thousands.

Shortly after his death, the first Viking raid struck at West Francia in 820 CE. This assault was easily repelled by the Shore Guard because the Vikings were surprised by the resistance they met; but they would return later in greater force and be far better prepared. In the 820's CE, Louis the Pious would still have been able to spare resources to support Egbert in Wessex but, as that decade progressed, he was contending with Slavic incursions, rebellions, and then a series of civil wars and so had his own problems to deal with.

Even so, contrary to the claims of a number of scholars, it is not as though Wessex declined in power after 830 CE. Mercia was an autonomous state by 831 CE, operating without regard to Wessex's interests, but it was nowhere near as powerful as it had been and never would be again. Scholars who claim Wessex declined in the 830's CE point to Egbert's defeat by the Vikings in 836 CE but this was a single loss to a previously unknown opponent and hardly characterizes a decline.

In 836 CE, the Danes invaded at Charmouth (modern-day Carhampton in Somerset) with a fleet of 35 ships and were met by Egbert and his army. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for that year states how “a great slaughter was made there and the Danes remained masters of the field” indicating a significant victory for the Viking raiders.

The Vikings appear to have made a treaty with the Cornish people of Dumnonia, who had been subject to Wessex since Egbert's campaigns in c. 815 CE. What exactly the Vikings did after the Battle of Charmouth is unknown but there is no doubt they remained in the region because, in 838 CE, they and the army of Dumnonia met Egbert and his army at the Battle of Hingston Down. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, the Viking-Dumnonia forces seem to have declared war on Wessex and taken up a position in present-day Cornwall, daring Egbert to meet them. The entry for 838 CE continues: “When he [Egbert] heard this, he proceeded with his army against them and fought with them at Hengeston where he put to flight both”, winning the field and dispersing the enemy.

Although Wessex did not retain the kind of power it had over Mercia after c. 830 CE, Egbert could still mobilize a force and win battles as late as 838 CE, one year before his death. His defeat in 836 CE, sometimes attributed to a lack of resources or support from Louis the Pious, could as easily have been caused by lack of preparation and surprise. Just as the Vikings were easily defeated by the Shore Guard of West Francia in 820 CE, it is likely that Egbert was defeated in 836 CE for the same reason: he had no idea what to expect from his opponents. The Vikings did not engage in battle the same way the West Franks or West Saxons did and, after Charmouth, Egbert knew this and was better prepared for them in 838 CE.

The King in Vikings & Legacy

Egbert died of natural causes in 839 CE and his son Aethelwulf succeeded him without opposition due to support from the church. In the TV series Vikings, Egbert is seen granting land to Viking settlers he will later betray, sending Aethelwulf to slaughter the Viking settlement, and later granting land to other Vikings when he has earlier secretly abdicated rule to Aethelwulf. None of these events has any historical basis but the seamless succession of Aethelwulf, with the support of the church, is the probable historical inspiration.

Throughout the character's appearance in Vikings, he is routinely depicted as clever, conniving, and untrustworthy which, as noted, has no historical basis but may draw upon supposition concerning his rise to power and consolidation of Wessex. Egbert is often characterized by historians as operating outside the boundaries of acceptable diplomacy. The historian Roger Collins, for example, refers to him as “the Kentish adventurer”, not a noble or prince, and credits his later prominence in history to “West Saxon propaganda” (196). Scholar C. Warren Hollister credits early Viking raids in the region with the consolidation of Wessex's power in that both Northumbria and Mercia had been destabilized by the Vikings beginning in c. 793 CE (127). The tendency among historians is to either downplay Egbert's contributions entirely or attribute them to double-dealing or later exaggeration.

Although later scribes quite likely did embellish on Egbert's lineage to link him with Cerdic, there is nothing in the contemporary accounts which support the claim that Egbert was anything less than a capable and efficient medieval king. It is probable that he did engage in duplicity and back-door deals to achieve his ends but in this, he would have been no different than Charlemagne or any other leader, past or present. The kingdom he stabilized and developed would pass to his successors until it was elevated to its height under the reign of Albert the Great and became the birthplace of the Kingdom of England; that would not have been possible without the contribution of Egbert of Wessex.