King Philip’s War (also known as Metacom’s War, 1675-1678) was a conflict in New England between a coalition of Native American tribes organized under the command of Metacom (also known as King Philip, l. 1638-1676), chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy and the English immigrants who had colonized Native American lands.

Metacom (also known as Metacomet) was the son of Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661) who, in 1621, had given much-needed assistance to the English colonists who founded the Plymouth Colony. Massasoit and the first governor John Carver (l. 1584-1621) had signed the Pilgrim-Wampanoag Peace Treaty in March of 1621 promising mutual aid and defense, and this treaty was honored by both sides until after Massasoit’s death.

The success of the Plymouth Colony encouraged further English colonization, and in 1630, John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649) arrived with 700 colonists on four ships to establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Massachusetts Bay expanded colonial land purchases from the natives as well as encouraging further colonization by exiles who objected to the puritanical rule of the Boston magistrates. These satellite colonies expanded English landholdings further, and with every acre the English claimed, more of the ancestral lands of the natives were lost.

Massasoit was succeeded by his son Wamsutta (l. c. 1634-1662) who was on good terms with the colonists and, like his brother Metacom, had been given an English name, Alexander Pokanoket, at his and his father’s request. In 1662, Wamsutta was summoned to the colonies by Josiah Winslow (l. c. 1628-1680), then assistant governor of Plymouth Colony, to answer charges concerning unfair land deals. Wamsutta died shortly after returning to his village, and Metacom, who succeeded him, claimed he had been poisoned. Metacom's claim was most likely true as Winslow had no regard for the natives and considered them obstacles to full English colonization.

Metacom continued to negotiate with the English to retain tribal lands, but as more agreements were broken and more promises unkept, he launched an all-out offensive to drive the English back which became known as King Philip’s War. Metacom was killed in 1676, but the tribes fought on until 1678 when they were defeated. Many of the natives were then sold into slavery or pushed onto reservations while others left the region voluntarily. The English policies regarding King Philip’s War were informed by Anglo-Native conflicts which preceded it and would inform the policies of the colonial governments and later US government policy toward Native Americans.

Plymouth Colony & the Wampanoags

The Plymouth Colony was founded in November 1620 and lost half its population to disease and malnutrition by spring 1621. From the time of their arrival until March 1621, they had been observed by the tribes of the Wampanoag Confederacy. Europeans had been arriving in the region by that time for over 20 years, and in 1614, the English Captain Hunt had kidnapped a number of natives to sell into slavery. Hunt had not been the first to do so nor the first to disrespect Native American lands and culture. The arrival of the Europeans had also brought disease, which had killed a significant number of natives who had no natural immunity to them.

Massasoit’s first impulse, therefore, was to call on the Higher Powers of the land to drive off or destroy the immigrants, but when it seemed his prayers would not be answered, he chose a different course. The Wampanoag Confederacy had been the most powerful political and military force in the land before it was reduced to tributary status by the loss of people to disease. The Wampanoags now paid tribute to the Narragansetts whereas, earlier, the situation had been the reverse. Massasoit saw in the survival of the English a sign that he should ally with them and restore himself and his tribe to its former position of power.

In March of 1621, he sent Samoset (l. c. 1590-1653), an Abenaki prisoner who spoke English, to the colony to find out if they were interested in peaceful relations. Samoset returned a good report and so Massasoit then sent Squanto (also known as Tisquantum, l. c. 1585-1622) and finally arrived himself with his warriors. On 22 March 1621, Massasoit and John Carver signed the so-called Pilgrim-Wampanoag Peace Treaty, pledging mutual aid and defense to one another, and Massasoit assigned Squanto the task of teaching the colonists how to survive. He later sent his trusted advisor Hobbamock (d. c. 1643) to lend further assistance and supervise Squanto.

In the early years of the settlement, the immigrants and natives took care of each other. Massasoit and his confederacy regained their former status, and the colony flourished. The second governor, William Bradford (l. 1590-1657) continued to honor the treaty and expanded trade with the Wampanoag while another leading colonist (and third governor), Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655), saved the life of Massasoit as well as those of a number of his tribe who had fallen ill. The head of the colony’s militia, Captain Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656), became close friends with Hobbamock just as Bradford did with Squanto.

Massachusetts Bay Colony

In 1630 CE, John Winthrop arrived in New England with 700 Puritan colonists to expand upon the small settlement of Massachusetts Bay, north of Plymouth. These new arrivals settled on land which had been previously claimed by John Endicott (l. c. 1600-1665) for England in 1628 CE. Although these were Native American lands, the villages had been deserted after the populace was wiped out by disease and so it seemed to Endicott to be free land for the taking. Massachusetts Bay Colony attracted more colonists from England between 1630-1640 in what came to be known as the Great Migration (also the Puritan Migration), and more lands were required for settlements and farming.

At the same time this influx of more immigrants was going on, religious dissension in Massachusetts Bay inspired further colonization elsewhere. Winthrop had founded the colony on the belief that those involved had a covenant with God which had to be honored if they hoped to not only survive but succeed. Religious dissent, which might threaten the covenant, was not tolerated and so those who broke from the official understanding of Christianity were exiled. Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683) was exiled in 1636 and founded Providence Colony in modern-day Rhode Island. Anne Hutchinson (l. 1591-1643) soon followed, founding Portsmouth, while others afterwards established settlements in Connecticut and New Hampshire.

The Native Americans did not fence in their land because they did not believe they owned it. They understood the land as a loan from the Divine and, while different tribes might fight over resources, conflicts were primarily over honor, subjugation for tribute, retribution for insult, but never for conquest. The Native American understanding of land rights also differed significantly from the English view and so, when they engaged in a transaction with the English, they saw it as a rental agreement, not a sale. They continued to plant crops and hunt on land 'sold' to the English because they still considered it their own.

Pequot War & Rampant Colonization

While the English were colonizing Massachusetts and Connecticut, the Dutch had established themselves in New Netherlands (modern-day New York State) and were encroaching on trade in Connecticut between the English and tribes such as the Pequot, who inhabited the coast of Long Island Sound and the interior of Connecticut. Conflicts between English and Dutch traders and their respective Native American partners began as early as 1633, and tension mounted in 1634 and 1636 when two English traders were killed by natives of the Western Niantic tribe who were allied with the Pequots.

The English seized on the deaths to start the Pequot War (1636-1638) which resulted in the near extermination of the Pequots. The Pequots had tried to enlist the powerful Narragansetts as allies against the English, advocating a guerilla war, striking without warning and vanishing away, to drive the English out, but the Narragansetts took the advice of Roger Williams – who spoke their language and had lived among them – and sided with the English, thereby dooming the Pequots.

The Treaty of Hartford of September 1638 divided Pequot lands between the English and their Native American allies, with the English claiming the best lands along the river. From there, they expanded further north and west into Connecticut. At the same time, more immigrants were arriving regularly from England and more land was taken from the Native Americans of the region, especially those of the Wampanoag Confederacy.

War Begins

Massasoit seems to have been unconcerned by these developments as he had no great love for the Pequots and, thus far, the English remained on the periphery of the central Wampanoag lands. He had envisioned a long-lasting English-Wampanoag alliance and so, with his sons’ consent, had them receive names from the English; Wamsutta was renamed Alexander, and Metacom was called Philip. After Massasoit’s death, Wamsutta became chief and negotiated land deals with the English of Rhode Island, which upset those of Plymouth Colony. He was called to give an account of himself by Plymouth’s assistant governor Josiah Winslow, son of the man who had saved Massasoit, and he died mysteriously shortly after returning to his village. Metacom then became chief, claimed Wamsutta had been poisoned, and he began discussing an attack on the colonies with his tributary chieftains.

The colonists had converted a number of natives to Christianity, and these so-called “praying Indians” often served as interpreters in trade agreements. One of these, John Sossamon, formerly Metacom's interpreter and scribe, told Winslow of Metacom’s plans but was ignored until after he was found dead. Metacom was then called to explain or refute Sossamon's claims and denied them. A few months later, three high-level Wampanoags, all counselors to Metacom, were arrested for Sossamon's murder and hanged on 8 June 1675. The agreement between Plymouth and the Wampanoags stipulated that each would be responsible for punishing their own, and the hangings violated this. On 24 June 1675, Metacom lay siege to the Plymouth Colony’s settlement of Swansea and destroyed it, killing many of the inhabitants.

Colonial Response

Throughout the summer of 1675, Metacom’s people seemed to be everywhere, attacking settlements, killing the people, and burning crops and buildings before disappearing again into the wilderness. They would frequently ambush supply trains or trade convoys, used the colonists’ own boats to reach settlements up- or downriver, and always employed the element of surprise and destruction by fire. The colonists had no defense against these attacks, and they were also at a loss to explain why the natives were suddenly attacking them. Scholar James D. Drake comments:

These Puritans’ fears stemmed partially from their inability to see Indian grievances as the cause for the war. Instead, with their providential worldview, in seeking to explain the war they looked to what might have made God, rather than the Indians, unhappy. (81)

Their solution was to call for days of fasting and repentance while, at the same time, trying to fend off attacks from an agency they felt had been sent by God to punish them for their sins. Scholar Jill Lepore gives a timetable for 1675:

- June 24 - Plymouth Colony observes a fast day.

- June 29 - Massachusetts Bay Colony observes a day of humiliation.

- July 8 - Massachusetts Bay Colony observes a day of humiliation.

- July 21 - Plymouth Church observes a day of humiliation.

- September 1 - Counties in Connecticut begin holding weekly fasts.

- September 17 - Boston observes a day of humiliation.

- October 7 - Massachusetts Bay Colony observes a day of humiliation.

- October 14 - Plymouth Colony observes a fast day.

- December 2 - All of the United Colonies observe a fast day in preparation for the campaign against the Narragansetts. (103)

Many colonists felt they were being punished by God for their treatment of the Native Americans but, instead of trying to address the problems, they continued begging God for mercy and deliverance from the scourge they believed God had sent against them while simultaneously trying to fight off forces whose attacks they interpreted as God’s will.

Great Swamp Fight & Battle of Mount Hope

The Narragansetts had remained neutral throughout 1675 but had agreed to shelter the women, children, and injured of the Wampanoag and other tribes engaged in the war. In December 1675, the colonists, under Josiah Winslow, attacked a Narragansett stronghold, burning it to the ground, and killing upwards of 600 Narragansetts as well as the women and children of other tribes who had been taken in. This event, known as the Great Swamp Fight, resulted in the Narragansett joining Metacom in waging the war. This, in turn, led to more fast days and days of humiliation as hostilities increased and the colonists wondered why.

Metacom shifted his base of operations from Rhode Island to New York, which had only recently passed from Dutch to English hands. He hoped to enlist the aid of the Mohawks, but they had already proven themselves friends to the English in the Pequot War and remained loyal to them at this time, attacking the Wampanoags and driving them back to New England. Metacom continued the war, striking at settlements throughout Massachusetts in the early weeks of 1676. On 10 February 1676, they attacked Lancaster, kidnapping Mary Rowlandson (l. c. 1637-1711) who would later write her famous captivity narrative about the experience. In Rhode Island, Providence and Warwick were burned to the ground.

The war continued as it always had, with colonists reduced primarily to reacting to attacks instead of being able to control the action. The attack on Sudbury settlement on 21 April 1676 left farms burned and over half of Captain Wadsworth’s militia dead. Even a decisive colonial win such as the Second Battle of Nipsachuck was a reaction to earlier Native American raids, not a calculated campaign. Captain Benjamin Church (l. c. 1639-1718) had begun increasingly relying on Native American soldiers in the war and especially made use of the “praying Indians” for intelligence, and this tactic finally shifted the balance of power in favor of the colonists.

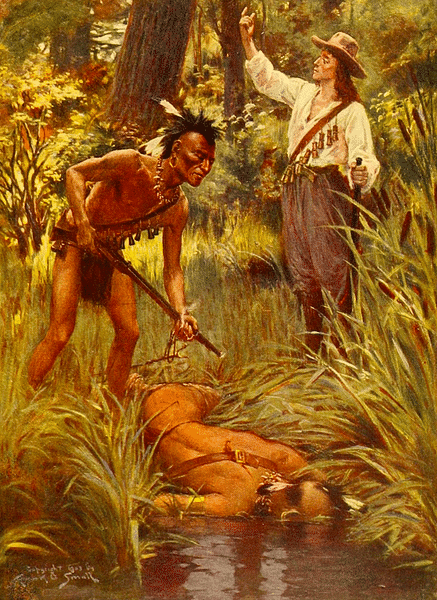

In early August 1676, Church and Josiah Standish (l. c. 1633-1690), both of Plymouth Colony, were led by the praying Indian John Alderman toward Metacom’s camp in the Assowamset Swamp near the ruins of Providence Colony. Alderman, who had been one of Metacom’s closest counselors before defecting, saw the chief and killed him with a gunshot to the back. Church gave Alderman Metacom’s head and hands as a trophy. Metacom’s body was then drawn and quartered and the parts hung from trees and palisades. Alderman stored the head and hands in a bucket of rum and, for a price, would show it to the curious until he finally sold the head to Plymouth Colony for 30 shillings. It remained on a pole in the colony for over 20 years.

Conclusion

The war in Massachusetts pretty much came to a close after Metacom’s assassination but continued in the north between colonists and natives of the Wabanaki tribe and their allies until 1678 when the Treaty of Casco was signed. By that time, the conflict had claimed thousands of lives on both sides, saw over half of the English settlements damaged or destroyed and native villages ruined, crop supplies had been burned, and numerous injuries would hamper survivors from being able to work the land as they had before.

The Pequot War, wholly contrived by the English for land, resulted in the dispersion of the Pequots with many of them enslaved and given to Mohegan and Narragansett allies and others sold locally or to slavers. After King Philip’s War, also instigated by the English through broken treaties and promises, this same policy was followed. In both cases, colonists were reacting to the fear of a widespread Native American uprising such as the Jamestown Colony settlements had experienced in March of 1622 when the Powhatan chief Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646) had killed 347 colonists in a single morning in what became known as the Indian Massacre of 1622. These fears were not groundless, either, as this is precisely the course suggested by the Pequots to the Narragansetts and, later, the plan Metacom envisioned for his own resistance to the English invasion.

Plymouth Colony, which would never have survived without Wampanoag assistance, sold over 1,000 Wampanoags and their allies into slavery in Bermuda and the West Indies and expanded their reach into former Wampanoag territory. Massachusetts Bay and the others also expanded as the surviving natives were pushed onto reservations or were absorbed by other tribes and left the region. Later alliances between natives with the English and French were influenced by relationships established during King Philip’s War which also informed later US policy toward Native Americans.

The war was not won by the English because of superior weapons or tactics. The colonial militias were poorly commanded, barely organized, groups of men armed with muskets which were far less effective than the bow and arrows of the natives. The war was won because of the lack of unity among Native American tribes, the seemingly inexhaustible supply of immigrants, and finally, through lies. The English made promises to the natives they had no intention of keeping and, just as with the understanding of land rights, this concept of making deals without any intention of honoring them was foreign to Native American culture and, ultimately, was the immigrants’ most powerful weapon.