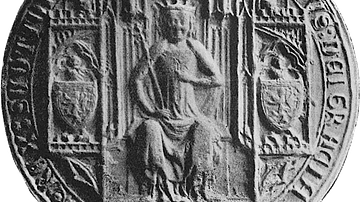

King Stephen of England, often called Stephen of Blois, ruled from 1135 to 1154 CE. His predecessor Henry I of England (r. 1100-1135 CE) had left no male heir and his nominated successor, his daughter Empress Matilda, was not to the liking of many powerful barons who preferred Stephen, the wealthiest man in England and nephew of Henry I. An on-off civil war ensued over the next decade and a half or so between the two sides while the English crown lost control of its territory in Normandy as well as lands to Scotland and the Welsh princes. Stephen was the last of the Norman kings, a line begun by his grandfather William the Conqueror in 1066 CE. He was succeeded by Henry II of England (r. 1154-1189 CE) who was, somewhat ironically given the previous civil war, the son of Matilda and Count Geoffrey 'Plantagenet' of Anjou.

Early Life

Stephen was born c. 1097 CE in Blois, France, his parents being Stephen Henry, Count of Blois and Adela of Normandy, the daughter of William the Conqueror and sister of Henry I. Stephen was sent to his uncle Henry's court from the age of ten and, establishing himself as one of the king's favourites, he received riches and lands. He also had a lucky escape in 1120 CE when the White Ship carrying Henry's heir William (b. c. 1103 CE) sank in the English Channel drowning all on board except a butcher from Rouen. If Stephen had not had a bout of diarrhoea, he would have been on the ship himself. If William had not died, then Stephen would almost certainly never have been king.

Stephen married Matilda of Boulogne (c. 1103-1152 CE) sometime in or prior to 1125 CE. Matilda was the daughter of Eustace III, Count of Boulogne and Mary of Scotland, daughter of Malcolm III of Scotland (r. 1058-1093 CE) and the sister of Henry I's wife. She would be a formidable ally in her husband's fight to keep his crown, both in terms of finances and leadership. Stephen was said to be good-looking, pious, chivalrous, and charming to everyone, even poor people. He would need all of these qualities to rally sufficient support around him in the coming decades.

Succession

Despite two marriages, King Henry I of England left no legitimate male heir and so his nominated successor was his daughter Matilda (b. 1102 CE) whom the king had made his barons swear loyalty to (including Stephen). Matilda is often called Empress Matilda after her marriage in 1114 CE to Holy Roman Emperor Henry V (r. 1111-1125 CE). Following the emperor's death, Matilda married Count Geoffrey of Anjou (l. 1113-1151 CE) in 1128 CE. The Count was also known by the nickname 'Plantagenet' because his family coat of arms included the broom plant (planta genista).

Despite Henry's wishes, many barons did not like the idea of a female ruler or the idea of a member of the house of Anjou as their sovereign and so they supported their own man Stephen, Count of Blois, then the richest baron in England. Stephen also had a very decent pedigree as a grandson of William the Conqueror and a nephew of Henry I. Crucially, at the time of the king's death in December 1135 CE, Stephen was the first to arrive in England while Matilda remained in France. Stephen also had the advantage of being a good military leader (if not being particularly talented at anything else) and control of the royal treasury at Winchester thanks to his brother Henry being bishop there since 1129 CE. Consequently, Stephen wasted no time at all and gathered enough baronial support to be elected king on 22 December 1135 CE. He was crowned four days later in Westminster Abbey. All was not well in his kingdom, however. Matilda's claim to the throne was supported by another group of barons and so an intermittent civil war broke out.

Empress Matilda & Civil War

Empress Matilda's husband Count Geoffrey was as ambitious as his wife to control England, and another even more important ally in Matilda's cause was Robert Fitzroy, Earl of Gloucester, an illegitimate son of Henry I. Initially, Robert Fitzroy had supported Stephen but he subsequently switched to Matilda's side in the civil war, although a premature uprising by his followers was ruthlessly crushed by Stephen in April 1138 CE. In fact, the king's opponents were mounting up as even his own brother, Henry of Blois, fell out of favour with him over who should control the see of Canterbury. Yet another enemy was Ranulf, the Earl of Chester, justifiably upset that the king had given away his castle at Carlisle to the Scottish king (see below for Stephen's border troubles). Unfortunately, the king could not always buy loyalty by giving out royal lands as his predecessor Henry I had already overused this strategy and left the Crown somewhat impoverished. In addition, barons now had the leverage to promote their own situations, some taking full advantage of the weakness in the monarchy to switch sides - Geoffrey de Mandeville infamously changed sides three times.

It is, then, with all these defectors and supporters of questionable loyalty around him, perhaps understandable that Stephen may have turned a bit paranoid at this point, perhaps explaining his arrest in 1139 CE of Roger, Bishop of Salisbury and two other bishops in the belief they were guilty of a treasonous plot.

Fortunately for the king, his situation brightened somewhat when Matilda arrived in England from France and was then captured in 1139 CE. The would-be queen was imprisoned in Arundel Castle in West Sussex. However, she was subsequently freed only to then audaciously establish a rival court in south-west England. Matilda's cause was bolstered by a rebellion on the other side of England in East Anglia against the imprisonment of the Bishop of Ely. The Earl of Chester then chose his moment to take Lincoln. The king responded by sending an army but then lost the battle of Lincoln on 2 February 1141 CE. Even worse, the king was arrested by Robert Fitzroy in April 1141 CE and imprisoned first at Gloucester and then Bristol for nine months. This was the lowest point of Stephen's reign and, at the time, it very much looked like the end of it.

Empress Matilda had herself elected queen at Winchester on 8 April 1141 CE. She then travelled to London in June 1141 CE to get ready for her coronation, but the city's people found her rule to be too self-interested and, with her irksome taxes another negative, a popular uprising drove Matilda from the city. The rebels were dealt another blow when royalists - in the form of an army of mercenaries from Flanders led by Stephen's wife Queen Matilda - captured Robert Fitzroy. Empress Matilda was obliged to release Stephen in exchange for Robert Fitzroy's freedom on 1 November 1141 CE. Stephen was then reinstated as king later in November in a dramatic turnaround of fortunes. Stephen even received a second coronation on 25 December 1141 CE, this time in Canterbury Cathedral. The civil war was far from over, though, and would rage on for several more years yet.

Unscrupulous barons took advantage of the chaos, sometimes known as 'The Anarchy', to seize new lands, build castles - still the ultimate medieval symbol of authority - without royal consent, and even mint their own coinage, another blow to the monarchy. The life of the peasantry was made thoroughly miserable in some parts of the country (but certainly not all) as they were caught up in (albeit infrequent) battles, many sieges, the occasional burning of entire villages and lawless barons imprisoning and torturing them without heed of the law. Even the clergy was at it, fortifying many churches and abbeys as the level of security in certain parts of the kingdom fell to its lowest in the entire Middle Ages.

The tide finally turned with two significant developments. The first happened in December 1142 CE when Matilda was besieged at Oxford and she only managed to escape the castle by braving a snowstorm wrapped in a white cloak. The Empress fled to a new base at the castle of Devizes in Wiltshire. The second development was the death of Robert Fitzroy at Bristol in 1147 CE, he who had been a crucial motivator for many rebel barons.

After six years shut up in her almost impregnable castle at Devizes, Matilda returned to Normandy, her focus now was the promotion of her son Henry of Anjou rather than herself. Henry inherited his father's lands in Normandy in 1151 CE, but he was ambitious for much more. Following military victories in Brittany and, in May 1152 CE, his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine (c. 1122-1204 CE), Henry came to control most of France. Still he wanted more and set his eyes on England, weakened as it was by years of civil war. Henry attempted an invasion in 1147 CE, but his campaign came to an end when he ran out of funds, obliging his return to Normandy. Another attack in 1149 CE, this time in the north of England and with the assistance of David I of Scotland (r. 1124-1153 CE), was defeated by an army of Stephen's. Henry, though, could bide his time and once he had much greater resources at his disposal, he tried another invasion in 1153 CE which, third time lucky, finally brought an end to the civil war.

Defending the Realm

While the country was ripped apart by the divided barons, the king was also threatened by the actions of his neighbours. The first to nibble away at Stephen's territory was the Count of Anjou, husband of Empress Matilda. He invaded Normandy in 1137 CE and despite Stephen's expedition there, the local barons proved less than willing to fight yet another war over this hotly contested territory. Stephen was obliged to withdraw and leave Normandy to fend for itself.

Meanwhile, David I of Scotland, the uncle of Empress Matilda, was flexing his muscles and attacked Northumbria, Lancashire, and Yorkshire in the north of England in 1138 CE. The Sottish king would eventually grab control of Cumberland, Northumberland, Durham, Westmorland, and Lancaster but was at least pushed back by Stephen's victory near Northallerton in Yorkshire at the battle of the Standard in August 1138 CE. In the east of Stephen's kingdom, 1146 CE saw the Welsh brothers Cadell ap Gruffydd (d. 1175 CE) and Maredudd win victories against English armies and so they significantly extended their territories into western Wales. The lack of a strong monarch who could concentrate on foreign affairs was costing the English kingdom dear.

Death & Successor

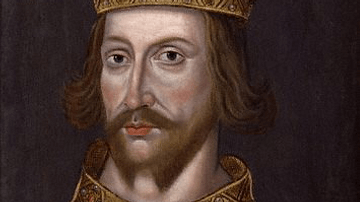

In 1153 CE, King Stephen was something of a broken man following the death of his wife and son Eustace (b. 1127 CE) that year. He now faced Henry's third invasion and hoped for a decisive pitched battle, but in the event, neither side's soldiers or leaders were very keen on a fight. Consequently, on 6 November, Stephen signed with Henry the Treaty of Wallingford, which recognised him as Stephen's official heir. In return, Stephen was allowed to keep his crown for the rest of his life. The barons had no better candidate to support than Henry, and it was clear to all that the civil war had not done anybody any good (even if its chaos has perhaps been exaggerated by later historians) and the last thing England needed was another tussle for the throne. As one anonymous medieval chronicler put it, "For nineteen long winters, God and his angels slept" (quoted in McDowall, 26). It was time for unity and peace. Consequently, when Stephen died on 25 October 1154 CE at Dover in Kent, Henry was crowned on 19 December 1154 CE and he became the first undisputed king of England for over a century. King Stephen was buried at Faversham Abbey in Kent alongside his wife and son, while the major episodes of the king's turbulent reign were recorded for future generations in the mid-12th-century CE chronicle Gesta Stephani.

During Stephen's reign, then, the lands in Normandy had been lost, and now the Norman line of kings came to an end. It was a watershed in English history. Henry would begin a new ruling dynasty, the Angevins-Plantagenets, and he would rule until 1189 CE, forming the largest empire in western Europe and putting himself down as a strong candidate for one of England's greatest ever kings.