The Kingdom of Abyssinia was founded in the 13th century CE and, transforming itself into the Ethiopian Empire via a series of military conquests, lasted until the 20th century CE. It was established by the kings of the Solomonid dynasty who, claiming descent from no less a figure than the Bible's King Solomon, would rule in an unbroken line throughout the state's long history. A Christian kingdom which spread the faith via military conquest and the establishment of churches and monasteries, its greatest threat came from the Muslim trading states of East Africa and southern Arabia and the migration of the Oromo people from the south. The combination of its rich Christian heritage, the cult of its emperors, and the geographical obstacles presented to invaders meant that the Ethiopian Empire would be one of only two African states never to be formally colonised by a European power.

Origins: Axum

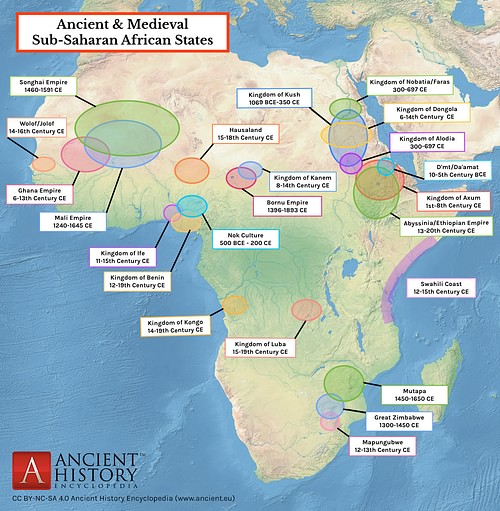

The Ethiopian Highlands, with their reliable annual monsoon rainfall and fertile soil, had been successfully inhabited since the Stone Age. Agriculture and trade with Egypt, southern Arabia, and other African peoples ensured the rise of the powerful kingdom of Axum (also Aksum), which was founded in the 1st century CE. Flourishing from the 3rd to 6th century CE, and then surviving as a much smaller political entity into the 8th century CE, the Kingdom of Axum was the first sub-Saharan African state to officially adopt Christianity, c. 350 CE. Axum also created its own script, Ge'ez, which is still in use in Ethiopia today.

Across this Christian kingdom, churches were built, monasteries founded, and translations made of the Bible. The most important church was at Axum, the Church of Maryam Tsion, which, according to later Ethiopian medieval texts, housed the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark, meant to contain the original stone tablets of the Ten Commandments given by God to Moses, is supposed to be still there, but as nobody is ever allowed to see it, confirmation of its existence is difficult to achieve. The most important monastery in the Axum kingdom was at Debre Damo, founded by the 5th-century CE Byzantine ascetic Saint Aregawi, one of the celebrated Nine Saints who worked to spread Christianity in the region by establishing monasteries. The success of these endeavours meant that Christianity would continue to be practised in Ethiopia right into the 21st century CE.

The kingdom of Axum went into decline from the late 6th century CE, perhaps due to overuse of agricultural land, the incursion of western Bedja herders, and the increased competition for the Red Sea trade networks from Arab Muslims. The heartland of the Axum state shifted southwards while the city of Axum fared better than its namesake kingdom and has never lost its religious significance. In the 8th century CE, the Axumite port of Adulis was destroyed and the kingdom lost control of regional trade to the Muslims. It was the end of the state but not the culture.

Kingdom of Zagwe

Bridging the gap between Axum and the Kingdom of Abyssinia was a third kingdom, that of Zagwe with its capital at Roha (300 km south of Axum). Founded in 1137 CE by a commander of Lasta in unclear circumstances, the new kingdom continued to promote Christianity in the region and still possessed many of the cultural and artistic traditions of Axum. The kingdom expanded from its heartland in northern Ethiopia thanks to a large and well-equipped army, especially in the pagan west and south. One famous king, Lalibela, ordered rock-cut churches to be built and such was their effect on the populace that the capital was renamed in his honour.

Christianity, still nominally led by the Patriarch of Alexandria, continued as a thread linking the various political states of Ethiopia's history. The country is dotted with over 1,500 churches carved out of rock. The designs generally follow the traditional Roman-Byzantine basilica form with aisles, galleries, and a domed nave but there are many variations such as the Church of Saint George at Lalibela (11-12th century CE) with its distinctive cross shape. The largest example is Beta Madhane Alem, also at Lalibela. Most of the churches cannot be dated due to lack of inscriptions and suitable remains, but they provide a convincing argument that Ethiopia did not suffer a cultural Dark Age between Axum, Zagwe, and the Kingdom of Abyssinia.

The Solomonid Dynasty

The medieval Kingdom of Abyssinia was founded by the Solomonid dynasty c. 1270 CE. Their first ruler was Yekuno-Amlak (r. 1270-1285 CE), a local leader at Amhara. It is likely that the Solomonids saw the kings of Zagwe as usurpers, an interruption to the dynasty that had ruled Axum, and they gathered the support of anti-Zagwe factions which had presented a continuous opposition throughout the 12th and 13th centuries CE. The Zagwe dynasty contributed to its own downfall by always having disputes over who had the right of succession - even the great Lalibela had been briefly deposed by his own nephew.

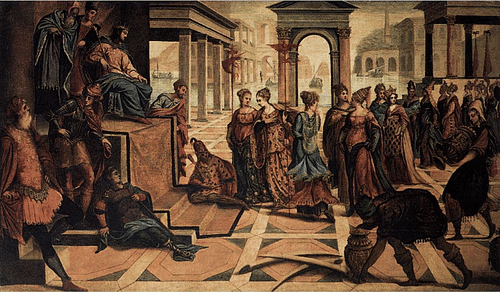

Yekuno-Amlak and his successors, according to both oral and written medieval traditions (which were mostly compiled in the 13th or 14th century CE like the Kebra Negast but possibly using older sources), claimed direct descent from the biblical King Solomon of Jerusalem and Makeda, the Queen of Sheba (equated with Ethiopia in this tradition but more likely to be southern Arabia), hence their dynastic name of 'Solomonid'. The story goes that the Queen of Sheba visited King Solomon in Jerusalem after hearing of his great wisdom. The royal couple enjoyed an amorous encounter, the fruit of which was a son called Menelik. When reaching adulthood, Menelik also went to Jerusalem and, thanks to one of his travelling companions, he came back to Axum with quite a prize, the Ark of the Covenant.

The claim may have been dubious - indeed, there is, in any case, no direct evidence of a historical King Solomon ruling Israel in the 10th century BCE - but it does seem that the Ethiopian kings themselves believed their heritage, or at least publicly claimed to. King Zara Yakob (r. 1434-1468 CE) was asked about his ancestry at his coronation and boldly stated: "I am the son of David, the son of Solomon, the son of Menelik" (quoted in Curtin, 141).

The claim may have been fabricated and was certainly perpetuated in order to give legitimacy to the Solomonid line. Many Solomonid kings held their coronation at Axum because of the Ark of the Covenant connection there. It is also interesting to note that in Ethiopian literature on what constitutes good kingship two things are held as vital - descent from a person, like Solomon, who had made a holy covenant with God and possession of the sacred Ark of the Covenant. Ethiopian kings were fortunate to claim both and, by association, the people of Ethiopia were able to also claim they were God's chosen people, a point reinforced by the Christian kingdom's isolation in East Africa, surrounded as it was by states which were predominantly Muslim, Jewish, or which practised traditional African beliefs. For the Ethiopian people, they were the 'second Israel'. That is not to say traditional African religion was wholly eradicated in Abyssinia; even the king performed a ritual sacrifice of a buffalo and a lion when he was crowned.

The Solomonids had their capital at Amhara, near Ethiopia's present-day capital, Addis Ababa. Although efforts to control coastal trade had some success, land trade routes and those along the Blue Nile proved more profitable for the Ethiopians. Territory was also disputed between the Solomonids and Muslim traders of the Red Sea who established such small states as Harar, Dawaro, Bale, and Adal. At the same time, the Solomonids expanded their kingdom in as many directions as possible to eventually carve out an empire which spanned from Shoa in the south to the lands north of Lake Tana at the other end of the compass.

The Ethiopian Empire

The Solomonid kings used several means to expand their territory: warfare, religion, and diplomacy, as here summarised by the historian P. Curtin:

It was the case also in Solomonid Ethiopia where…the kingdom spread to areas where Christians did not form a majority of the population. Small colonies of Christians who lived beyond the kingdom's borders served as the advance guard of royal expansion. They stayed on after conquest, and were joined by additional colonies of the king's soldiers. In the first stages of conquest a defeated ruler, a non-Christian who had been independent, might remain in office, but now as a subject of the king and now ruling over Christian settlements that were in touch with the king. There were many royal strategies for keeping control of this territory. The king often required the tributary chief to send a number of his children and other relatives to live at his court. They served as hostages in case of rebellion, and they also came to learn how to behave as Solomonid courtiers. (147)

To entice colonists to settle in the new territory, reward administrators, and further cement Solomonid control, land grants were awarded known as gult. Recipients then had the right to extract personal tribute from the farmers who worked that land. These combined strategies were particularly successful in conquering the Shoa mountain area.

One of the most successful Solomonid rulers in terms of empire-building was Amda Seyon I (r. 1314-1344 CE) who doubled the size of his territory which now spread down from the Red Sea to the Rift Valley. Amda Seyon also had the clever idea of confining all his male relatives - except his sons - within a monastery at Gishen. The king's successors followed the same strategy, and thus succession disputes, or at least all-out civil wars, were largely avoided until the mid-16th century CE.

Another great king was Zera-Yakob who found time not only to write several treatises on Christianity but also to deal crushing defeats on the coastal Muslim states in the mid-15th century CE. Spreading Christianity through Holy War was a major aim of the kingdom's campaigns. Fortunately for posterity, Amda Seyon ensured he always had with him on campaign a priest who wrote down choice episodes. This anonymous priest recorded the events he witnessed in his work The Glorious Victories of Amda Seyon. Here is an extract from it:

Now be not afraid in face of the rebels; be not divided, for God is fighting for us…For long you have made yourselves ready to fight for me; now be ready to fight for Christ, as it is said in the Book of Canons, 'Slay the infidels and renegades with the sword of iron, and draw the sword in behalf of the perfect faith.' Gird on then your swords, make ready your hearts, and be not fearful in spirit, but be valiant and put your trust in God. (quoted in von Sivers, 459)

In the mid-15th century CE, the influence of Coptic Egypt continued in Abyssinia with Solomonid kings adopting and adapting a Christian version of the old Roman law, The Law of the Kings (Fetha Nagast), which Egyptian Copts had codified into a single volume of laws which applied to everything from church matters to criminal punishments. It would remain in effect in Ethiopia until the 20th century CE. In addition, there were other contacts with the wider Christian world such as an Ethiopian embassy to the Pope in Rome in the early 14th century CE and exchanges of embassies with several European powers as the Crusades proved ever more disappointing in their attempt to regain control of Jerusalem from the Muslims. Indeed, for a time, European Christians, and particularly the Portuguese, believed that the legend of Prester John, a mythical Christian king thought to rule a fabulous kingdom in the midst of the Muslim world, referred to the king of Abyssinia who would surely come and rescue the Holy Land from the infidels. Aside from sending a steady stream of pilgrims to Jerusalem, however, Abyssinia did not involve itself in the major crusades.

Later History

The Ethiopian Empire's imperialism in the long term only ensured the Muslim states of East Africa and Southern Arabia eventually organised themselves into a more collective and efficient opposition. At the same time, internal rivalries between the Solomonids and their distinct lack of any centralised state apparatus (despite the attempts of several noted rulers) weakened Abysinia's ability to respond. The Solomonids would suffer greatly at the hands of Adal in the first half of the 16th century when its leader, Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (aka Ahmed Gragn, r. 1506-1543 CE), formed a coalition of other Muslim states and Somali chiefs. Many Christian churches were torched, the monastery of Debra-Libanos was destroyed, and even Axum was sacked. Ottoman Egypt and Portuguese traders became involved in East African affairs, only adding to the disruption in trade networks and general political chaos.

The real winners, though, of the incessant Muslim-Christian wars were the Oromo (aka Galla) people, who had their own traditional religion and who took over the southern part of Abyssinia. The Solomonid line would continue but the empire they had created really existed in name only until a revival in the mid-19th century CE. In the meantime, the state was rather a collection of quarrelsome principalities. The move of the capital to the more centrally-placed and secure Gondar in 1636 CE was a reflection of the new geopolitical reality. There would still be some Ethiopian highpoints to come such as the defeat of an Italian invasion in 1896 CE, the unification and expansion under Menelik II (1889-1913 CE), and managing to remain the only African country along with Liberia not to be formally colonised by a European power, but the long line of Solomonid rulers eventually ended with perhaps their most famous of emperors, Haile Selassie I (r. 1930-1974 CE).