The Kingdom of Benin, located in the southern forests of West Africa (modern Nigeria) and formed by the Edo people, flourished from the 13th to 19th century CE. The capital, also called Benin, was the hub of a trade network exclusively controlled by the king or oba and which included relations with Portuguese traders who sought gold and slaves. Benin went into decline during the 18th century CE as the kingdom was racked by civil wars, and it was ultimately conquered by the British in 1897 CE. Today, the kingdom is perhaps best known for its impressive brass sculptures and plaques which frequently depict rulers and their family; they are considered amongst the finest artworks ever produced in Africa.

Origins: The Nok & Ife Tradition

The region of southern West Africa was introduced to (or developed itself) iron-working technology from at least the 9th century CE. With better tools to use in agriculture, crop yields improved. Peoples of the rain- and dry forest belt which runs across the southern part of West Africa made clearings for their villages and successfully grew crops such as yams, bananas, and oil palm kernels.

The Kingdom of Ife, located in today's Nigeria like the Kingdom of Benin, flourished between the 11th and 15th century CE. The kingdom produced many fine cast bronzes, especially expressive sculptures of human heads. Ife had perhaps been influenced by the earlier Nok Culture (5th century BCE to 2nd century CE) and Igbo-Ukwu (at its zenith in the 9th century CE). In Benin oral traditions, it was the king of Ife who sent a master craftsman southwards to Benin in the late 13th century CE to spread his sculptural skills, and this may reflect the historical movement of iron-working Yoruba peoples in the territory of the Edo in Benin. The Edo tradition also states that it was they who invited Prince Oranmiyan of Ife to rule them and it is his son, Eweka, who became the first king of Benin.

As the art historian, P. Garlake states, "The myths and traditions of the city of Benin point to Ife as the origin of kingship and brass casting" (139). Points of similarity between the art of the two cultures include the use of a leopard in connection with death and snakes, such as those which entwine the gables of the Benin palace and a relief from Ife. Archaeology, however, has yet to establish any firm connection between these states which successively dominated the southern portion of West Africa above the Bight of Benin.

Historical Overview

The Kingdom of Benin was located near the southern coast of West Africa in a region which is today southern Nigeria (the modern state of Benin is further along the coast to the west and named after the Bight of Benin). The territory is a mix of rainforest, dry forest, and mangrove swamp. Formed in the 13th century CE as a state proper, the Kingdom of Benin was populated by the Kwa-speaking Edo people and covered at its peak an area of some 400 kilometres (250 miles) in length and 200 kilometres in width. The heartland was a circle around the capital, also called Benin, extending some 60 kilometres in all directions and was ruled directly by the king. Next came an outer band of territory governed by royal princes and finally a third ring of tribes which offered tribute to but were not directly ruled by the king of Benin.

The kingdom prospered thanks to regional trade with Benin seemingly acting as a middle-trader between other kingdoms, passing on goods which it did not produce itself such as cotton and semi-precious stone beads. Other goods exchanged between West African peoples included fish, salt, yams, and cattle, to name a few. Such was the well-established nature of these trade relations, there is evidence of native currencies being used which took the form of manillas (heavy horseshoe-shaped bracelets), wiring and rods all made from metals like copper, brass, and bronze. There is also evidence that cowrie shells - which came via Persia and the Maldives - were used as a currency in Benin before direct European contact, a fact which points to trade with northern African savannah kingdoms who would have acquired them via land trade routes.

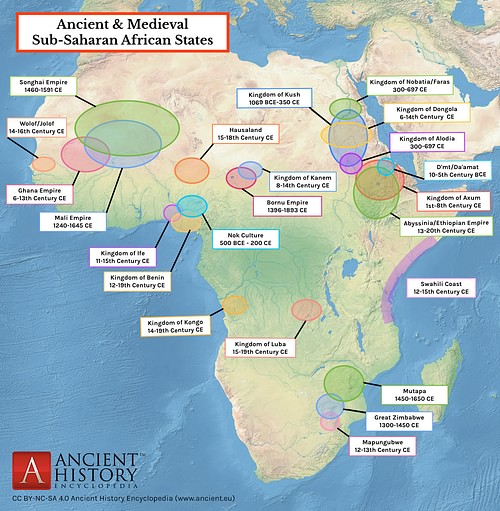

From around 1450 CE Portuguese ships were sailing down the Atlantic coast of Africa and offering an alternative to the trans-Saharan caravan routes and those trade networks between Africa's interior kingdoms. From 1471 CE, these ships were accessing the aptly-named Gold Coast in the south of West Africa in search of the gold that had provided such wealth for the Mali Empire (1240-1645 CE) and Songhai Empire (c. 1460 - c. 1591 CE). Suddenly, the southern peoples of West Africa, who had been at the very end of the trade chain which started in Europe and then went through North Africa, the Sahara, and the West African savannah, now found themselves at the opposite end of a booming maritime trade as ships landed directly from Europe. Benin was not a coastal state but it did maintain contacts there via the port of Ughoton on the Benin River.

Following the Portuguese colonization of Sao Tome and Principe in the 15th century, Benin traded with the Portuguese, who established a 30-year presence at Ughoton from 1487 CE. The Europeans were interested in beads, cotton cloth, ivory, and slaves, which they could then trade on to other West African peoples in exchange for what they prized most of all: gold and pepper (the only two goods in demand in Europe). West African tribes sought, too, the fine cotton cloth of India, glass beads, and cowrie shells which the Portuguese brought to Africa. Benin must also have had an insatiable demand for copper and leaded bronze, needed to make the brass for their famous sculptures. The king of Benin imposed strict control on his kingdom's trade, creating a royal monopoly. Indeed, the king clearly had a strong bargaining position with the Europeans because he prohibited the sale of male slaves after 1516 CE because he needed them for his own army.

In 1514 CE the king of Benin initiated diplomatic relations with the Portuguese government by sending an embassy to Europe, seemingly with the motive of negotiating a shipment of firearms to be sent to his kingdom. The Portuguese were not inclined to arm a potential enemy and instead sent a number of Christian missionaries to try, as had been attempted elsewhere in Africa, to convert the ruler and thus his people to Christianity. The king remained loyal to his traditional beliefs, and although some churches were built and a few Africans did convert, the project to spread Christianity was largely abandoned for what it was, a flimsy veil of decency to hide the Portuguese policy of stripping the land of all valuables as quickly and cheaply as possible. Neither were there any attempts made to install any kind of administrative apparatus, an ambition which was, in any case, severely hampered by the high mortality rates of Europeans once they encountered local diseases. It would only be from the 19th century CE that European missionaries really started to attack indigenous beliefs in West Africa.

The King or Oba

The kings of Benin had the title of oba and were considered to have a divine right to rule. The king not only controlled all trade with outsiders but also personally owned the vast majority of high-value goods in the kingdom such as leopard skins, pepper, coral, and ivory. Many rulers are commemorated in Benin art. Ivory masks, intended to be worn at the hip of rulers, show kings with crowns and necklaces of human heads, perhaps Europeans, and signifying either the oba's monopoly over trade or his dominance over foreigners. Kings often feature in the brass plaques that adorned the palace of Benin where they appear as warrior leaders. They can be identified by symbols of their rank such as leopard-spot scarification marks and leopard-tooth necklaces. The leopard was an appropriate symbol for the oba since the animal was considered the 'King of the Bush' and only the king was permitted to kill one, typically done in an annual sacrifice by the king for his own honour. Other royal symbols seen in depictions of Benin kings are a helmet with coral embellishments and mask ornaments worn around their waists, which are white, a colour symbolic of both purity and the king's counterpart in rule, Olokun, the god of the sea and source of wealth and fertility. Just like gods and the spirits of ancestors, the kings received offerings and sacrifices, including humans ones, after their death.

Perhaps Benin's greatest king was Ewuare the Great (r. 1440-1473 CE) who was regarded not only as a great warrior but also a powerful magician. He is credited with overseeing a period of particular prosperity and expanding the kingdom to its greatest area but is also charged with murdering his brother and establishing the role of oba as an absolute monarch. Ewuare formed the system of government which would persist for the rest of the duration of the Kingdom of Benin. The king was advised by a group of titled and hereditary chiefs and another group of chiefs appointed by the king to govern specific towns. In addition, Ewuare created the convention that a king's eldest son would inherit the throne from his father. The English naval officer Thomas Windham visited Benin in 1553 CE, and his account of the court of the Benin king is as follows:

…the king sat in a huge hall [with nobles] cowering…upon their buttocks with their elbows upon their knees and their hands before their faces, not looking up until the king command them.

(quoted in Fage, 517)

The City of Benin

Benin, the capital of the kingdom, is located some 30 kilometres (18.6 miles) from the coast and to the west of the Niger River. Excavations at the city have revealed that it was once surrounded by high earthworks but, as there are many gaps, it is not thought that these were for a defensive purpose. The walls may have served to demarcate different kin groups within the capital, all loyal to the king but each having their own outlying farmland. The city would have been further divided into districts for craftworkers who belonged to guilds.

The king, his court and the palace were both the political and spiritual heart of the kingdom of Benin. The palace had many courtyards and several galleries with wooden pillars to support the roof. Attached to these pillars were the brass plaques which are considered one of the high-points of West African art from any period.

Benin Bronzes & Other Arts

The sculptures produced in Benin using brass (although often termed 'bronzes') have become world famous for their execution and artistry. Production boomed from the end of the 15th century CE with the arrival of the Portuguese who brought great quantities of brass for trade. The lost-wax technique was used from this period (as opposed to smithing prior to the 16th century CE) to produce sculptures of all kinds, but one particular speciality was plaques. Rectangular and around 45 centimetres in height, these panels show figures in high relief, very often of warriors and rulers. Originally attached to wooden pillars in the royal palace of Benin, many of the plaques commemorate historical conflicts, show scenes of life at court and Benin religious rituals.

Besides plaques, Benin artists produced life-size brass sculptures of heads, small but full human and animal figures, and ceremonial bells. Ivory was another medium that Benin craftworkers favoured, carving it into the hip masks mentioned above and also extremely ornate and intricate boxes, combs and armlets. As already mentioned, masks were carved from ivory to be worn around the waist of kings, and a magnificent pair survive, one now in the British Museum London and the other in the Metropolitan Museum of New York. Both masks may depict Idia, the mother of King Esigie who ruled in the 16th century CE.

It is likely, too, that many Benin sculptors worked with wood, but this material hardly ever survives very long in Africa due to the ravages of climate and insects. The artists of Benin were not averse to producing works specifically for the Portuguese market either, carving such items as ivory salt cellars with European horse riders or casting brass soldiers bearing muskets, all with a uniquely African twist.

Decline & Later History

Other European nations besides the Portugues became interested in West Africa by the late 16th century CE, including the British, French, and Dutch. Britain, determined to loosen the Benin kings' grip on trade, conquered the kingdom in 1897 CE, which had already been severely weakened by a long series of dynastic disputes and civil wars. However, the kings were not displaced entirely and descendants of Benin's royal dynasty still hold the title of oba today as they perform an advisory function to the government of Nigeria. The name Benin lives on, too, as it was revived by the French colony of Dahomey when it declared independence in 1975 CE and became the Republic of Benin.