The Kingdom of Israel occupied that part of the land on the Mediterranean Sea known as the Levant which corresponds roughly to the State of Israel of modern times. The region was known, historically, as part of Canaan, as Phoenicia, as Palestine, Yehud Medinata, Judea and, after the Romans destroyed the region in 136 CE, as Syria-Palaestina.

According to the Bible, the region was named after the Hebrew patriarch Jacob, also known as Israel (from Yisrae'el, meaning to `persevere with God') and, by extension, his nation. Israel was the region colonized by Abram (later Abraham), developed by his son Isaac and grandson Jacob, and later allegedly conquered by the Hebrew General Joshua around 1250 BCE, following the Exodus from Egypt under Moses.

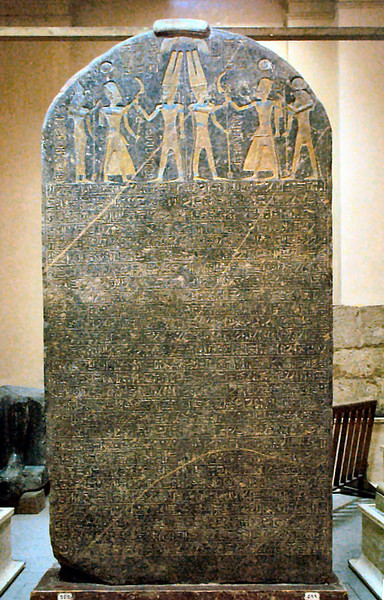

Israel as a cultural entity is first mentioned in the stele of the Egyptian pharaoh Merenptah (r.1213-1203 BCE) in which he states that “Israel lies devastated, bereft of its seed” (Kerrigan, 59). The reference seems to be to a people, not a kingdom, but no scholarly consensus has been reached on a final meaning nor even why Israel should be mentioned on a stele which celebrates an Egyptian victory over the Libyans unless the Israelites were part of the coalition known as the Sea Peoples, which is improbable.

By c. 1080 BCE the Israelites had established a kingship in the land and developed a culture which drew on earlier civilizations. As scholars J. Maxwell Miller and John H. Hayes note:

Roughly two thousand years of recorded history and impressive cultural achievements preceded the beginnings of Israelite and Judean history. This earlier span of time witnessed major literary, technological, and scientific developments, particularly in Mesopotamia and Egypt. [Artifacts] unearthed at ancient sites in Palestine illustrate that the Israelites and Judeans were heirs to a long and sophisticated civilization. (27-28)

This interpretation of history is at odds with the traditional belief that the Israelites appeared in Canaan and imposed their culture on a pre-existing population following a military conquest of the region.

The kingdom split in two following the death of King Solomon (r.c. 965-931 BCE) with the Kingdom of Israel to the north and Judah to the south. In 722 BCE the northern kingdom was destroyed by the Assyrians and the population deported as per Assyrian military policy (resulting in the so-called Lost Ten Tribes of Israel). Judah was destroyed by the Babylonians in 598-582 BCE and the most influential citizens of the region taken to Babylon.

The Persians, following their conquest of the Babylonian Empire, returned the Israelites to their homeland in 538 BCE and held the region as part of their empire until it fell to Alexander the Great (l.356-323 BCE). Following Alexander's death, the region was held by Ptolemy I and then the Seleucid Empire until c. 168 BCE when the Israelites revolted under the leadership of the Maccabees who established the Hasmonaean Dynasty. The region was taken by Rome in 63 BCE and the people's resentment against foreign occupation resulted in periods of more or less unrest until the Bar Kochba Revolt of 132-136 CE in which the Jews were defeated, Jerusalem destroyed, and the area renamed Syria-Palaestina by the Roman emperor Hadrian.

Biblical Narrative

According to the narrative in the biblical Book of Genesis, the patriarch Abram led his people to the land of Canaan as directed to by his god (12:1-5). In Canaan, Abraham and then his son Isaac and then his son Jacob (Israel) established the culture of the Hebrews (literally “wanderers”). Jacob had twelve sons but favored his youngest, Joseph, which enraged his brothers and so they sold him to the Ishmaelites as a slave and he was then re-sold in Egypt. Once there, he rose to prominence through his ability to interpret dreams, and became a powerful administrator who saved the region from starvation during a famine. At this time, Joseph's brothers and father came and settled in Egypt as welcome guests (Genesis 37, 39-47). According to the Book of Exodus, in time, the Israelites became too populous and were enslaved by the Egyptians (1:7-11).

The Israelites remained in bondage until they were liberated by Moses the Lawgiver who brought them to the land of Canaan, which had been promised to his people by their god. Moses was unable to enter the land himself owing to a misunderstanding with this god and passed his leadership to his second-in-command, Joshua, who then led the Israelites to victory over the indigenous people and divided the land among his own (Deuteronomy 32:51-52, Joshua 1-19). This version of history and the military conquest of Canaan, it should be noted, is only found in the Bible and, while archaeological evidence in the region once known as Canaan does support wide-spread upheaval in the region between c 1250-c. 1150 BCE, said evidence does not fit neatly with the biblical narrative.

Whether there was such a general named Joshua and whether the Hebrews did, in fact, conquer the Canaanites is a matter of belief in the biblical narrative. It has been established, however, that something of moment did occur c. 1250-c.1150 BCE (the Bronze Age Collapse) which resulted in a displacement of indigenous people, not only in Canaan, but elsewhere throughout the Near East. Some modern-day scholars completely reject the claim of a conquest and point to archaeological evidence to support their contention that the Israelites peacefully assimilated with the Canaanites and that belief in a conquest of the region by an Israelite general only emerged much later during the period of the Babylonian Captivity of 598-538 BCE and was only codified as part of the biblical narrative during the Second Temple Period (c.515 BCE-70 CE).

The counter-claim to the biblical narrative is that Abram was an Amorite in Mesopotamia who relocated to Canaan and that later Hebrew scribes, unsatisfied with their ancestral ties to Mesopotamia, created a new history which highlighted their people's unique relationship with the one true God of the universe in order to establish political superiority. They elevated a minor Canaanite deity, Yahweh, to the level of supreme being and then instituted religious practices to further distance themselves from others in the region.

This theory, as Miller and Hayes point out, is just as largely guesswork and belief as acceptance of the biblical narrative but also note that extra-biblical documentation and archaeological evidence suggest that the region at this time “was something of a melting pot, composed of diverse elements living under various `ad hoc' political and religious circumstances [which] formed the basis of the later kingdoms of Israel and Judah” (78). According to this theory, there was no conquest but only a gradual assimilation of immigrants into the general population of the region.

The First Kings

Israel developed into a united kingdom under the leadership of King David (c.1035-970 BCE) who consolidated the various tribes under his single rule (having taken over from Israel's first king, Saul, who ruled c. 1080-1010 BCE). David chose the Canaanite city of Jerusalem as his capital and is said to have had the Ark of the Covenant moved there. As the Ark was thought to contain the living presence of God, bringing it to Jerusalem would have made the city both a political and religious center of considerable importance. David intended to build a great temple to house the Ark but that task fell to his son, Solomon whose rule corresponds to the height of Israelite grandeur as depicted in the Bible.

Solomon consolidated treaties with neighboring kingdoms such as Tyre to the north, Egypt, Sheba and sponsored building projects which made Jerusalem a great and opulent city (including, of course, the First Temple). The reigns of Saul, David, and Solomon (but especially the latter two) have been traditionally characterized as a `golden age' of unity and prosperity although scholars have noted that the biblical account itself records economic difficulties which led to ceding cities to the Phoenicians (I Kings 9:10-14) and Solomon's brutal policies which led to Judah breaking away from the kingdom after his death (I Kings 12:1-20).

The religion of the Kingdom of Israel was henotheistic (a belief in many gods with a focus on a single most powerful deity among them) and David, as Saul before him, emphasized the preeminence of the god Yahweh as the focus of worship. David and Solomon, especially, seem to have used this belief to their benefit in unifying the people but after Solomon's reign the kingdom split in half, Israel occupying the northern region with a capital at Samaria and the Kingdom of Judah in the south with Jerusalem as capital. The two kingdoms would thereafter sometimes ally and sometimes war but would never again achieve the strength and wealth of the kingdom during the reigns of David and his son.

Later Kings & Foreign Conquerors

The Kingdom of Israel prospered under the reigns of the kings Omri (c.876-869 or 884-872 BCE) and Ahab (c.876-853 BCE) and, later, Jehu's dynasty (842-746 BCE) according to archaeological evidence and the biblical narrative, but seems often characterized by instability resulting from the rivalry between Israel and Judah. Even so, under Ahab's reign, Israel was a major military power as evidenced by the Stele Inscription of Shalmaneser III of Assyria (859-824 BCE) who states that Ahab was able to field a massive army against him consisting of over 2,000 chariots and 10,000 infantry (although modern scholarship has contested these numbers).

By the time of the reign of King Hezekiah of Judah (c.715-686 BCE), however, Judah had become the more powerful of the two kingdoms. In 722 BCE the kingdom of Israel fell to the Assyrians under Sargon II (r.722-705 BCE) and, as per Assyrian policy, the population was relocated to other regions (resulting in the Lost Ten Tribes of Israel). Miller and Hayes note:

Israel ceased to exist as an independent kingdom quite early in the period of Assyrian domination. Its capital at Samaria was captured in 722 BCE, and Israelite territory was incorporated subsequently into the Assyrian provincial system. Judah maintained its national identity throughout this period but was almost completely dominated by Assyria. (314)

The exception to this domination was the city of Jerusalem which withstood Assyrian aggression. Hezekiah, according to the Bible, witnessed the fall of Samaria and focused on preparations to protect his capital city of Jerusalem. He was able to prepare Jerusalem to withstand the Assyrian siege of 703 BCE under Sargon II's son Sennacherib (r.705-681 BCE) through the construction of the Siloam Tunnel and Broad Wall, which can still be seen today but, even so, afterwards paid the Assyrians tribute as a vassal state.

When the Assyrian Empire fell in 612 BCE to a coalition led by the Babylonians and Medes, the Babylonians took the region, sacked Jerusalem, and destroyed the temple in 598 BCE. The Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (r.634-562 BCE) then deported the aristocracy, scribes, and skilled craftsmen back to Babylon, an event known as the Babylonian Captivity. Further Babylonian military campaigns from 589-582 BCE destroyed the Kingdom of Judah.

Babylon was conquered by the Persians under Cyrus the Great (d. 530 BCE) who released the Jews to return to their homeland in c. 538 BCE. The destruction of their cities, and deportation from a land they believed had been promised them by their god, forced the Jewish clergy to re-think their religious beliefs.

Religion

Prior to this event – and, in fact, throughout all of Israel's early history – the belief system of the people was henotheistic. Although the Bible generally presents a picture of a people who were unwavering in their monotheism, there is evidence even in those narratives that the people recognized and worshipped other deities such as the Ugaritic goddess Asherah, the Phoenician god Baal, and the Sumerian sun god Utu-Shamash, among others. The tribal desert god Yahweh, as noted, was advanced as the supreme deity as early as the reign of King Saul.

As in many ancient belief systems (and modern ones), faith in Yahweh relied on quid pro quo – an agreement, spoken or unspoken, that one would receive what one desired in return for something else. The people were expected to honor Yahweh and worship him and, in return, he would help them and keep them safe. When the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem and its temple and deported the leading citizens, some reason had to be found for why God had abandoned them and, exiled in Babylon, the Hebrew clerics concluded it was because they had not worshipped Yahweh exclusively. The Babylonian Captivity, then, was the turning point in Israelite religious belief and practice and, moving forward, it would be characterized by a strict monotheism.

The era encompassing the return of the Jews to their homeland and the revision of their religious beliefs is known as the Second Temple Period (c. 515 BCE-70 CE), so-named because of the construction of a temple on the site of Solomon's temple which had been destroyed by the Babylonians in 598 BCE. The Babylonian Captivity and resulting reformation of belief essentially created the religion of Judaism as recognized today. The synagogue, rabbinical schools, and the canonization of Hebrew scripture can all be traced initially to this time even though other reforms would emerge later during and after the Jewish-Roman Wars.

The Maccabean Revolt & Hasmonaean Dynasty

The Achaemenid (Persian) Empire held the region until it was conquered by the armies of Alexander the Great in 334 BCE. As he did in every region he conquered, Alexander introduced Hellenistic beliefs and cultural values in the region of Judea which some Jews accepted and others rejected. Following Alexander's death in 323 BCE, the region formerly known as the Kingdom of Judah was taken by his general Ptolemy I, who also held Egypt, but was lost to the Seleucids of Syria in 198 BCE. The Seleucids held the region until the edicts of their king Antiochus IV Epiphanes (174-163 BCE) to establish Hellenistic religious practices in the region (and especially the temple in Jerusalem) brought about the Maccabean Revolt of c.168 BCE.

The Maccabean Revolt (c.168-160 BCE) concluded in victory for the Jewish forces and the consecration of the temple (commemorated by the festival of Chanukah). Although traditionally viewed as an insurrection by religious freedom fighters (led by Judas Maccabeus) against foreign occupation and religious oppression, it is possible that the revolt began as a civil war between Jews who had embraced the Hellenism of the Seleucids and the traditionalists who rejected it and Antiochus IV became involved as an ally of the Hellenistic Jews.

However that may be, the Israelite victory over the Seleucids enabled them to found the Hasmonean Dynasty which would be the last independent Jewish kingdom in the region. The Hasmonaeans (possibly so named for Asmoneus, an ancestor of the Maccabees) engaged in a policy of expansion in which they claimed for themselves important trade centers formerly controlled by the wealthy Kingdom of Nabatea on their border. These policies brought them into conflict with the Nabatean kings and also with each other for control of the kingdom.

The wealth of the Nabatean Kingdom and civil wars of the Hasmonean Dynasty attracted the attention of Rome. In 64 BCE, Pompey the Great took Nabatea and, in 63 BCE, intervened in Hasmonean affairs and involved the region in his later power struggle with Julius Caesar. Although Hasmonean rulers still sat on the throne, Rome's intervention signaled the end of the independent kingdom. Rome installed their hand-picked king Herod the Great in 37 BCE and Judea became a client-state of the empire.

Revolts & the Destruction of Judea

The people of Judea resisted the occupation by Rome, however, and tensions finally erupted in the First Jewish-Roman War (also known as the Great Revolt) of 66-73 CE which concluded with the Roman general Titus destroying Jerusalem and laying siege to the mountain fortress of Masada. The defenders of Masada killed themselves rather than surrender or be taken and with their deaths the last resistance was broken and a large part of the population scattered or were sold into slavery.

The second significant revolt was the Kitos War (so-named from a corruption of the name of Lucius Quietus, the Roman general who put down the revolt, also known as the Second Jewish-Roman War) of 115-117 CE which resulted in further wide-scale slaughter and displacement of the population. The final, and most significant, revolt was the Bar-Kochba Revolt (also known as the Bar Kokhba Revolt and the Third Jewish-Roman War) of 132-136 CE. Although there were many factors contributing to this conflict, the flashpoint was emperor Hadrian's decision to build a new city, Aelia Capitonlina, on the ruins of Jerusalem and construct a temple to the god Jupiter on the holy site of the Jews, the Temple Mount.

Led by Simon bar Kochba, the revolt was initially successful and he was able to establish his authority and rule the region for three years until the rebellion was crushed by Rome. Thousands of people were slaughtered and others scattered. Hadrian exiled all Jews from the region and prohibited their return on pain of death.

Following the destruction of Judea and the resulting diaspora, Israel ceased to exist until the creation of the modern State of Israel in 1947-1948 CE by the United Nations. This link between the ancient Kingdom of Israel and the modern state of the same name has been hotly contested through the years and continues to remain a contentious subject of debate.