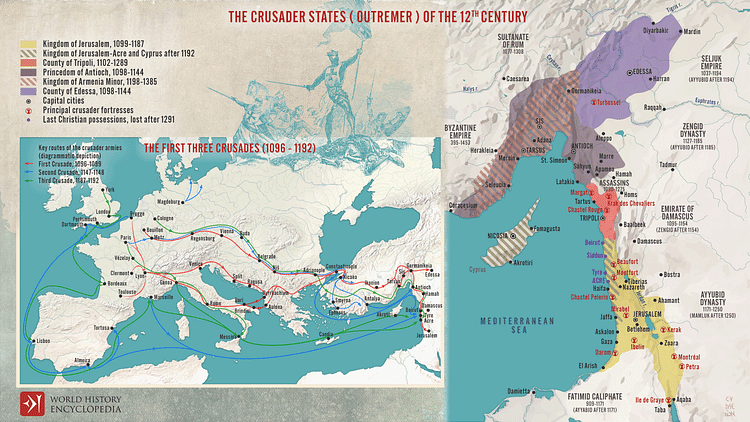

The Kingdom of Jerusalem was a state created in 1099 CE by Crusaders and western settlers after the First Crusade (1095-1102 CE). With Jerusalem as its capital, the kingdom was the most important of the four Crusader States in the Middle East, known collectively as the Latin East or Outremer. Relatively prosperous for two centuries as Europeans created a new life for themselves in a narrow strip of land on the eastern Mediterranean coast, it was, nevertheless, constantly troubled by political disunity and the threat of invasion. Several crusades could not save the kingdom, even though it limped on after the loss of Jerusalem in 1187 CE and the move of the capital to Acre. The kingdom was finally abolished and absorbed into Muslim Mamluk territories in 1291 CE.

Foundation: The First Crusade

Pope Urban II (r. 1088-1099 CE), following an appeal from the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118 CE), launched the First Crusade of western armies in November 1095 CE in order to recapture Jerusalem from Muslim control. The Seljuk Turks and their Sultanate of Rum had taken over parts of Asia Minor previously controlled by the Byzantine Empire and, more significantly for the West, the holy city (from rival Muslims) in 1087 CE. In a stupendously successful campaign, which would never again be repeated by subsequent crusades, the great cities of Nicaea and Antioch were captured and then, after a brief siege, Jerusalem too, on 15 July 1099 CE. Most of the original army of Crusaders returned home triumphant, but some nobles and their followers stayed on to begin a new life in the Holy Land. It was to be only the opening chapter in a very long story to keep hold of the hard-won territory against various Muslim rulers over the next two centuries. The situation of Christians in the Middle East was not helped either by the soured relations with the Byzantine Empire, the western leaders feeling that Alexios had not done very much to help the Crusaders. To defend the gains of the First Crusade, four Crusader states, collectively known as the Outremer or Latin East, were created: The Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Edessa, the County of Tripoli and the Principality of Antioch.

Monarchy & Government

The Kingdom of Jerusalem was the most important of the Crusader states, controlling a narrow strip of coastal lands from Jaffa in the south to Beirut in the north. Under the kingdom's control were the fiefdoms of Acre, Tyre, Nablus, Sidon, and Caesarea, amongst others. In addition, there was Cyprus, a handy Christian base for western ships to stop and resupply. The king of Jerusalem could ask for military assistance from the other Crusader states, but they were not obliged to give it and often did not. The king did have the help of the military orders like the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller, specialist knight-monks who were the best-trained fighting men in the Levant and who were given particularly important passes and castles to guard. The orders owed allegiance to none but themselves, though, and they could sometimes act contrary to the king's plans. This lack of political unity between the Crusader states and the absence of a single cohesive fighting force, would, in the end, greatly contribute to their downfall.

Godfrey of Bouillon, who had been one of the key leaders during the siege of Jerusalem in the First Crusade, was made the first king of Jerusalem and given command of a small garrison in the city (around 300 knights and 2,000 infantry). The Norman Arnulf of Chocques was made patriarch or bishop of Jerusalem. Godfrey might be king, which made him head of the High Court and commander-in-chief of the army, but he and his successors would constantly have to wrangle with the nobles. These barons were large landholders, the men who had led their own contingents of warriors during the Crusade and had grabbed what they could of former Seljuk territory. Theoretically, the barons were supposed to give military service (a quota of knights) to the king but could refuse to do so in practice if they considered he had broken his oath to respect their independence.

There would follow two centuries of complex intermarriages of noble families, regents on the throne, usurpers, four brief civil wars, and endless disputes over the succession - not very much different from any other European medieval state, then. Still, the king of Jerusalem remained the most prestigious position in the Latin East and if he (and in one instance she) were a reasonably capable ruler and did not suffer any military disasters, the monarch could expect to rule largely unchallenged. The king could also gain favour by granting land and titles (from those he acquired as his king's right to all lands of nobles who died without an heir). He might also distribute lands in such a way as to distance troublemakers from court or separate like-minded neighbours. He did, in any case, consult his nobles on matters of policy. The large estate owners, along with leading church figures and representatives of the military orders, attended a regular public debating forum, a parlement, in which opinions were aired and decisions made on such issues as taxes and foreign diplomacy.

Population & Integration

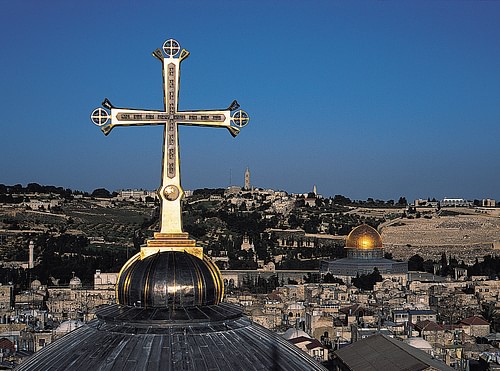

The Crusaders had come from across Europe, although most were from France (Normandy, Lorraine, and Languedoc) and Flanders. Not only nobles and knights, they included more humble workers such as blacksmiths, builders, bakers, and butchers. The western settlers were collectively known in the region as the 'Franks'. They lived in established cities and towns, and many new villages sprang up, especially where land was given to settlers as an encouragement to stay. Here housing, churches, monasteries, convents, and graveyards were built. The capital was the largest city with a population of around 20,000 when the kingdom was created, rising to around 30,000 by the late 12th century CE. Perhaps the most important and long-lasting of the capital's building projects was the new church of the Holy Sepulchre. Completed in July 1149 CE, the church replaced a smaller version on the site considered to be the place of Jesus Christ's crucifixion and the tomb in which he was buried.

Initially, as the kingdom established itself, there were massacres of local populations, but the westerners soon realised that to hold on to their gains they needed the support of the extraordinarily diverse locals. Consequently, there grew a toleration of non-Christian religions, albeit with some restrictions and with an inferior legal status than Catholic Christians. Jews and Muslims could visit Jerusalem but not reside there, for example, but there were never any anti-Jewish pogroms in the Latin East as there were in contemporary Europe. There were many Eastern Christians, especially Armenians, in the Kingdom, but even more Muslims, perhaps outnumbering the Christian population 5:1. The locals had been living in a feudal system under the Seljuks, and the same system continued under the Crusader settlers who, along with their families, would have numbered no more than a few thousand.

As most Crusaders came from France, the official language of the kingdom was langue d'oeil, which was then spoken in northern France and by the Normans. The linguistic and religious barriers, as well as those between ruler and ruled, meant that there was very little cultural integration between groups, rather, contact was limited to legal, economic, and administrative affairs. If there was any cultural integration it was most felt on the Franks' side and their adoption of local clothes, cuisine, and hygiene practices more suitable to the climate of the Middle East, as well as their sponsorship of local artists and architects. Despite the on-off warfare between the Christians and Muslims, the majority of the cities of the kingdom remained cosmopolitan as trade thrived regardless of politics or race.

The Franks particularly lacked manpower, and as a result, their influence over rural areas in the Crusader states was minimal. Indeed, the very borders of the Kingdom of Jerusalem were ill-defined, especially between the kingdom and the territories around Damascus, with each city controlling fortifications which tried, with varying success, to impose their rule on the land thereabouts. The regional politics of the various Muslim states and semi-independent cities added to the instability; Damascus, in particular, was keen to remain independent from the Egyptian Ayyubid Dynasty (1171-1260 CE) and sometimes entered into truces and alliances with the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The new kingdom attracted a small but steady stream of settlers from the west, who were encouraged by a gift of land as long as 10% of their produce was given to the local lord. Those farmers already long-established were permitted to keep their land by the Franks but had to contribute anything up to one-third of their produce (or half in the case of olives and wine) to their new Frankish overlords. Merchants came too, from the Italian states of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa, in particular, although high mortality rates, especially amongst infants, meant that the local Christian population did not grow significantly. There were many pilgrims, too, who paid a tax for the privilege and bought souvenirs like palm fronds and guidebooks of the holy sites. Some pilgrims also temporarily served in the army protecting the capital. Still, the situation was that the Crusader states were always reliant on western support whether it be people, money or arms. The Crusader states were not, then, colonies in the modern sense of the term, where distant lands were exploited for resources to benefit the homeland. Neither was there a large-scale migration to the new territories, another typical feature of colonisation. Rather, the states benefitted from an irregular influx of some settlers and western soldiers who participated in crusades and then returned home, much like the Christian pilgrims of the period.

Economy

The coastal plains of the Kingdom of Jerusalem were particularly fertile and a great source of wealth, helped in their productivity by still-in-use Roman aqueducts and irrigation channels and new ones built by the Franks. Sugarcane was a big-earner, indeed, most sugar consumed in Europe in the 12-13th century CE came from the Crusader states. Other crops included wheat, maize, millet, barley, fruit, olive oil, wine, and cotton. Fabrics were exported, especially silk and linen. Trade passing from east to west (spices, dyes, wood, ivory, metals, and manufactured goods) was a lucrative source of revenue as duties were imposed (4-25% of the goods' value or volume). Acre, for example, had replaced Alexandria as the most important trading port in the eastern Mediterranean and welcomed traders from Byzantium, North Africa, and Arabia. Although the kingdom had its own small naval fleet, ships were generally hired to purpose from Sicily, the Byzantine Empire, and the Italian cities of Venice, Pisa, and Genoa. The people, too, were taxed, more so in times of war when armies had to be raised. The Kingdom minted its own gold and silver coinage but was usually short of cash despite the benefits of agriculture and trade, largely due to the huge expense of building fortifications, castles and maintaining a well-equipped army, as well withstanding losses in territories and goods because of warfare with their Muslim neighbours.

The Second Crusade

Over the course of the 12th and 13th century CE, more crusades would be launched by western leaders to defend the interests of the Latin East. The Second Crusade (1147-1149 CE) was launched to recapture Edessa in Upper Mesopotamia which had fallen in 1144 CE to Zangi (r. 1127-1146 CE), the Muslim independent ruler of Mosul (in Iraq) and Aleppo (in Syria). The Crusade was a complete failure and Zangi's successor, Nur ad-Din (sometimes also given as Nur al-Din, r. 1146-1174 CE), captured Antioch in 1149 CE and then eliminated the Latin state of Edessa. It was an ominous sign of things to come for Jerusalem.

The Third Crusade

Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1174-1193 CE), was the next great enemy of the Crusader states. He heavily defeated a Latin army led by the Kingdom of Jerusalem at the Battle of Hattin in July 1187 CE and then, shortly after and with no one left to defend it, Jerusalem itself was taken in September. This disaster caused Pope Gregory VIII (r. 1187 CE) to launch the Third Crusade (1189-1192 CE). Faring a little better than the previous crusade, Acre was captured in 1191 CE but, without sufficient resources to capture and keep it, Jerusalem was left in Muslim hands. Acre thus became the new capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Latin East as a whole.

The Sixth Crusade

When the Fourth Crusade (1202-1204 CE) attacked Constantinople instead of the Muslim world, and the Fifth Crusade (1217-1221 CE) met with disaster on the Nile, it looked like the Christians would never rule Jerusalem ever again. Hope springs eternal, though, and, against all predictions, they did indeed regain the city from 1229 to 1243 CE, this time thanks to diplomacy, not warfare. The Sixth Crusade (1228-1229 CE), led by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (r. 1220-1250 CE) negotiated from the Ayyubid Sultan of Egypt and Syria, al-Kamil (r. 1218-1238 CE), the handover of the Holy City in 1229 CE. Al-Kamil was having his own internal problems over Damascus as well as having to face a threat to his territory in northern Iraq, so the concession of Jerusalem was given to avoid a damaging war over a prize that had little economic or military value. Under the deal, Muslims were to leave Jerusalem but could freely visit their own holy sites on pilgrimage.

Destruction

Despite the regain of Jerusalem, Acre remained the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, a wise decision given that the Holy City would soon be lost, yet again. This time it was to the allies of the Ayyubid Dynasty, the nomadic Khorezmians (Khwarismians) who captured it on 23 August 1244 CE. The Ayyubid control of the Middle East was greatly strengthened when a large Latin army and its Muslim allies from Damascus and Homs was defeated at the battle of La Forbie (Harbiya) in Gaza on 17 October 1244 CE. Over 1,000 knights were killed in the battle, a disaster from which the Crusader states never really recovered. A Seventh Crusade (1248-1254 CE) was launched, but like the Fifth Crusade, it got bogged down in Egypt and ended a flop. Its leader, Louis IX of France (r. 1226-1270 CE) did stay on in the Middle East and helped to refortify some of the cities of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, notably Sidon, Jaffa, and Caesarea. One final major Crusade, the Eighth Crusade (1270 CE), again led by Louis IX and again attacking the Ayyubids in Egypt, was another failure, and this time it was the last.

In between these last two crusades, a new threat had appeared in the region in the form of the Mongol Empire. The Mongols, moving relentlessly westwards, made raids on Ascalon, and Jerusalem. When a Mongol garrison was established at Gaza, an attack on Sidon quickly followed in August 1260 CE. Meanwhile, the Egyptian-based Mamluks (1250-1517 CE) had taken over from the Ayyubids. Their leader was the brilliant general Baibars (r. 1260-1277 CE) who managed to push the Mongols back to the Euphrates River and take over much of the Latin East so that only two pockets remained around Acre and Antioch. Then mighty Antioch fell in 1268 CE and Acre in 1291 CE; the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Latin East now only existed as a refuge on Cyprus, and the Holy Land was definitively lost to the Christians.