The Kingdom of Mercia (c. 527-879 CE) was an Anglo-Saxon political entity located in the midlands of present-day Britain and bordered on the south by the Kingdom of Wessex, on the west by Wales, north by Northumbria, and on the east by East Anglia. It was founded by the semi-legendary king Icel (r. c. 515 – c. 527 CE) who migrated from Germany with his tribe, later known as `Iclings', to the region of East Anglia and then to the midlands.

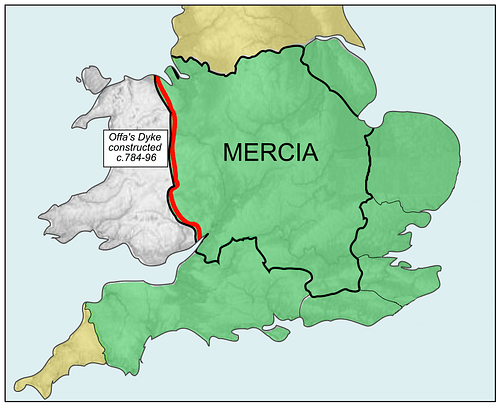

For its first 100 years, Mercia struggled to maintain its boundaries and defend its interests from neighboring kingdoms but that changed with the reign of Penda (r. c. 625-655 CE) who initiated the period of Mercian strength which reached its height under Offa (r. 757-796 CE), the greatest of the Mercian monarchs, best known for the 148-mile-long (238 km) dyke he had constructed along his border with the Welsh kingdoms.

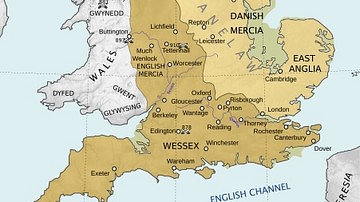

Mercian power was broken by King Egbert of Wessex (r. 802-839 CE) and, as Wessex grew in power, Mercia declined and was further weakened by repeated Viking raids. Independence was first lost in 879 CE when Ceolwulf II (r. 874-883 CE) submitted to Viking sovereignty and became their puppet king. It was later controlled by Wessex under Alfred the Great (r. 871-899 CE) and lost any autonomy completely under his son Edward the Elder (r. 899-924 CE).

Early History & Kings

Icel established an urban center at Tamworth which would become the capital (later possibly moved to Repton). Although he seems to have been king as early as 515 CE, the date of Mercia's founding is given as 527 CE based on the 13th century CE chronicles known as the Flores Historiarum. Icel was succeeded by his only son Cnebba (r. c. 535 - c. 545 CE) who was then succeeded by his son Cynewald (c. 545 - c. 580 CE); very little is known of their reigns other than approximate dates.

The lack of information on these and later kings – as well as much of Mercian history – is due to the Viking raids and wars with Wessex. Scholar Roger Collins comments:

The Viking conquests of the ninth century and the wars of the tenth apparently so effectively destroyed the material and intellectual records of the Mercian kingdom that all that now survive are a handful of charters, a small number of manuscripts (notably the Book of Cerne), some splendid if fragmentary stone carvings in the church of Breedon-on-the-Hill, and the great frontier dyke that Offa (almost certainly) built between his realm and those of the Welsh kings. Of the Mercian laws, which did exist, and of the kingdom's historiography, which might have done, few elements survive. (194)

While this is true, enough of these records survive to be able to piece together a chronology of the kings and the development of the kingdom. The next king, Creoda (r. c. 580-c.595 CE), gave away whatever holdings Mercia had to the east and these would develop into the Kingdom of East Anglia. His successor, Pybba (r. c. 595 - c. 606 CE), consolidated the kingdom and pushed its boundaries west.

This may have resulted in the Battle of Chester in c. 616 CE and possibly involved Pybba's successor Cearl (r. c. 606 - c. 625 CE) about whose reign little is known (it is even unclear who he was or how he came to power). Aethelfrith of Northumbria (r. 593-616 CE) defeated the Welsh and their allies, including (possibly) Cearl. The causes of the battle are unclear but it is possible Aethelfrith was responding to Mercian aggression since Cearl was the overlord of the eastern Welsh kingdoms.

He was succeeded by Penda, son of Pybba, last of the pagan kings of Mercia, who elevated the kingdom to the most powerful in the region. Penda defeated the West Saxon king Cynegils (r. 611-643 CE) at the Battle of Cirenchester in 628 CE and took the Severn Valley and Kingdom of Hwicce from Wessex. He then allied with the Welsh king Cadwallon ap Cadfan (r. c. 625-634 CE) to defeat Edwin of Northumbria (r. 616-633 CE) at the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633 CE. Edwin and his son were killed and the Kingdom of Northumbria collapsed; Penda expanded Mercia to the north and west. In 642 CE Oswald of Northumbria (later known as St. Oswald, r. 634-642 CE) rallied his troops to reassert Northumbria's power but was defeated and killed at the Battle of Maserfield.

Penda's religious beliefs were considered a significant factor in his victories. All of the kings who fought against him had been Christian and his unbroken record of military success argued for the supremacy of the pagan gods over the new Christian faith. By 650 CE, Penda controlled large portions of both Wessex and Northumbria and had strong alliances with East Anglia and the Welsh kingdoms.

In 655 CE, however, he was challenged by Oswald's brother Oswiu (r. 642-670 CE) who controlled the northern region of Northumbria. Penda marched on Oswiu in November 655 CE but was defeated and killed at the Battle of the Winwaed. The Northumbrian victory resulted in the Christianization of Mercia (since it seemed clear the Christian god of Oswiu was stronger than Penda's) and division of the kingdom. Penda's son and successor, Peada (r. 655-656 CE) converted to Christianity before taking the throne and every Mercian king after him would be Christian.

Oswiu divided Mercia in half, leaving Peada the south and ruling the north directly between 655-658 CE. Oswiu was overthrown and driven out by Wulfhere (r. 658-675 CE), one of Penda's sons, who ignored Northumbria and concentrated his efforts on the south. He was defeated at the Battle of Bedwyn in 675 CE by Aescwine of Wessex (r. 674-676 CE) who reclaimed southern regions from Mercia.

Wulfhere was succeeded by another of Penda's sons, Aethelred I of Mercia (r. 675-704 CE), who went in the other direction: he ignored the south and concentrated on Northumbrian relations. He established a clear boundary between the two kingdoms and secured an alliance by marrying into the Northumbrian royal family.

Almost nothing is known of the reigns of the next two kings, Coenred (r. 704-709 CE), son of Wulfhere, and Ceolred (r. 709-716 CE), Aethelred I's son. Ceolred was succeeded by Aethelbald of Mercia (r. 716-757 CE) who expanded the kingdom to the south and east and secured his boundaries. He lost territory in 752 CE to Cuthred of Wessex (r. 740-756 CE) who restored his kingdom's primacy in the region at Mercia's expense. Aethelbald was succeeded by Beornred (r. 757 CE) who reigned briefly until he was overthrown by Offa.

King Offa of Mercia

Offa is considered the greatest king of Mercia and the most significant Anglo-Saxon monarch before the rise of Alfred the Great. He reigned for 39 years, during which time he conquered the Kingdom of Kent, took Sussex, and arranged for the marriage of his daughter Eadburh (c. 787-802 CE) to Beorhtric, king of Wessex (r. 786-802 CE) and so easily controlled that kingdom as well. Offa established strong diplomatic relations with rulers on the continent, most notably Charlemagne the Great (King of the Franks 768-814 CE, Holy Roman Emperor, 800-814 CE) and improved Mercia's economy through trade.

He is best known, however, for a marvel of medieval engineering: Offa's Dyke. This is a barrier, surviving in the present as ruins, which runs along the border between Wales and England. Offa campaigned against the Welsh at least four times in the course of his reign and it is known there were frequent Welsh incursions into Mercia. The dyke was probably built as a barrier to prevent or slow these invasions but any records of its purpose or construction have been lost; the only mention of Offa as the dyke's builder is from Asser (d. c. 909 CE), biographer of Alfred the Great.

That aside, the dyke is an enduring symbol of Offa's power and supremacy in the region. By c. 794 CE he was so powerful that he was able to take control of East Anglia by ordering the death of their king and assuming his position; he did not even have to muster an army. The prosperity of this period has characterized it as the “golden age” of Mercia.

Wessex, Vikings, & Decline

Unfortunately, this affluence would not last long beyond his reign. Offa was succeeded by his son Ecgfrith (r. 796 CE) who was assassinated after a reign of less than 150 days (most likely in retribution for the various nobles Offa had killed to secure his son's succession). He was succeeded by Coenwulf (r. 796-821 CE), a descendant of Penda. Coenwulf struggled to hold his southern territories against rebellions while maintaining his northern boundaries. He was succeeded by his brother Ceolwulf I (r. 821-823 CE) who seems to have failed at every aspect of kingship and was deposed by the nobleman Beornwulf (r. 823-826 CE).

From 802 CE, Wessex had been ruled by King Egbert who had been quietly building an army and equipping it. In 825 CE, Egbert and his son Aethelwulf (r. 839-858 CE) defeated Beornwulf at the Battle of Ellandun and broke Mercian supremacy in the region forever. Egbert claimed the Mercian territories of Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Surrey and left Beornwulf only the center of his once great kingdom. East Anglia was able to throw off Mercian dominance and sided with Wessex and Beornwulf was killed trying to suppress this rebellion in 826 CE. His successor Ludeca (r. 826-827 CE) died trying to do the same.

Ludeca was succeeded by Wiglaf (r. 827-829, 830-839 CE) who was driven from the throne by Egbert in 829 CE. In 830 CE, however, Wiglaf managed to win back his throne and assert Mercian independence, most likely through negotiations with Egbert. He was succeeded by his son Wigmund (r. 839-840 CE) who was succeeded by his son Wigstan (r. 840 CE) about whom next to nothing is known. Wigstan was succeeded by Beorhtwulf (r. 840-852 CE) who was the first Mercian king to experience the Viking raids.

In 842 CE the Vikings sacked the Mercian city of London and left but they returned in 851 CE with a fleet of 350 ships which sailed up the Thames and attacked Canterbury and London again. Beorhtwulf raised an army to oppose them and his efforts may have been instrumental in driving them towards the south where Aethelwulf of Wessex and his sons Aethelbald and Aethelstan defeated them.

Beorhtwulf was succeeded by Burgred (r. 852-874 CE) who married Aethelwulf's daughter Aethelswith (c. 838-888 CE) to secure an alliance with Wessex against future Viking attacks. In 865 CE the Great Heathen Army of the Vikings landed at East Anglia and struck first at Northumbria before making their way back down south to Mercia. In 874 CE, they drove Burgred from the throne and he fled to Rome where he later died. He was replaced by Ceolwulf II who was hand-picked by the Vikings as their puppet-king. Ceolwulf II ceded the eastern part of Mercia to the Vikings for colonization in 879 CE and it became part of the Danelaw (region of Britain dominated by Danish laws and customs) while Ceolwulf II was allowed to govern in western Mercia by consent of the Danes.

Wessex Takes Mercia

Ceolwulf II was succeeded by Aethelred II (r. 883-911 CE) who refused to submit to the Danes and allied himself with Alfred the Great. Under the terms of this alliance, Aethelred II had to accept Alfred as his overlord and to secure the contract he married Alfred's daughter Aethelflaed (r. 911-918 CE). Alfred had defeated the Vikings in Wessex in 878 CE at the Battle of Eddington and secured his kingdom against future attacks through a system of burhs (fortified towns), a more efficient military, and the construction of a navy. He suggested Aethelred do the same in Mercia.

In 886 CE, Alfred conquered the Danes of London and was recognized as king of the Anglo-Saxons but this did not resolve the problem of Viking attacks and Aethelred had been too busy fighting off raids and administering his kingdom to initiate Alfred's system of burhs. In 892 CE the Vikings struck Mercia under the command of the legendary leader Hastein (also known as Hasting, 9th century CE). Between 892-896 CE, Aethelred was constantly fending off Hastein's attacks with the help of Alfred.

Alfred died in 899 CE and his son Edward the Elder succeeded him. Edward sent his young son Aethelstan to the Mercian court in 900 CE to be raised by Aethelflaed while he continued his offensive against the Vikings in Wessex. Aethelred fell ill about this time and Aethelflaed took charge of the government, organizing the military defense of Chester against a major Viking attack in 907 CE. Aethelred died in 911 CE and Aethelflaed succeeded him. With Edward, she initiated the burh system in Mercia along all the main routes from neighboring kingdoms.

Aethelflaed designed and constructed these burhs between 912-917 CE, all of which would later grow into towns and cities, while also fighting off Viking raiders and governing her lands. When she died in 918 CE, she was briefly succeeded by her daughter Aelfwynn (r. 918 CE) before Edward annexed Mercia completely under his own reign. When Edward died, he was succeeded by Aethelstan who would rule as King of the Anglo Saxons 824-927 CE and as the first King of England from 927-939 CE.

Mercia in Vikings & Legacy

In the TV series Vikings, Mercia is depicted as a chaotic kingdom from whence Queen Kwenthryth escapes to ask Ecbert of Wessex for help in regaining her throne. Ecbert enlists the aid of the Vikings under Ragnar Lothbrok to defeat the forces of Kwenthryth's uncle and brother and, this done, Kwenthryth then poisons her brother Burgred and proclaims herself queen, returning to her kingdom. In actual history, none of these events took place.

The historical Cwenthryth was the daughter of King Coenwulf of Mercia and was an abbess at the parish village of Minster-in-Thanet who was involved in a dispute over rent with the Archbishop of Canterbury after her father's death in 821 CE. A later scribe of the 12th century CE, most likely upset over her challenge to church authority, used her as the villainess in his story of the murder of St. Kenelm but there is no historical basis for that tale. The character on the show is based on this legendary version of Cwenthryth and also on two other women: Queen Cynethryth, wife of King Offa, and her daughter Eadburh, both of whom had a reputation as scheming and devious queens.

None of these women were related to the Mercian king Burgred who, unlike his depiction in the show, was neither a rapist nor a weak-willed man easily led by others. Burgred, in fact, was strong enough to withstand Viking attacks for years and defend Mercia ably until he was defeated and deposed. The chaotic nature of the Mercian court and nobility in the show is drawn from the reigns of various monarchs, Offa among them, who tended to eliminate people who interfered with their plans.

Unlike the depiction in the TV series, Mercia was not a discordant kingdom easily taken or manipulated by other kings. At its height, it was the most powerful kingdom in Britain and, were it not for the later reign of Alfred, Offa of Mercia would most likely be remembered today for establishing the Kingdom of England. Alfred and the kings of Wessex, as well as the rulers of Northumbria, have always been more widely known than those of Mercia. These kingdoms had something which Mercia did not, however: written records which survived to tell their story.