The architecture of ancient Korea is epitomised by the artful combination of wood and stone to create elegant and spacious multi-roomed structures characterised by clay tile roofing, enclosures within protective walls, interior courtyards and gardens, and the whole placed upon a raised platform, typically of packed earth. The immediate topography of buildings was also important as architects endeavoured to harmoniously blend their designs into the natural environment and take advantage of scenic views. The work of Korean architects is also seen in fortification walls and tombs across the peninsula ranging from Bronze Age dolmens to the huge vaulted enclosures of ancient Korean kings.

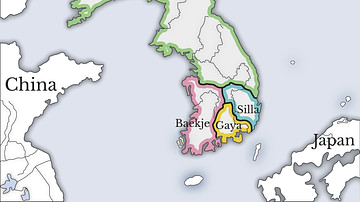

The architecture of ancient Korea (in this article the period prior to c. 1230 CE) is best described in relation to the three most distinct periods of Korean history within our timeframe: the Three Kingdoms period from the 4th to 7th century CE when the Silla, Goguryeo (Koguryo), and Baekje (Paekche) dynasties ruled the peninsula; the Unified Silla Kingdom, which ruled from 668 to 935 CE; and the Goryeo (Koryo) Dynasty which ruled from 918 to 1392 CE. Before covering these periods, though, Prehistoric Korea does provide some interesting examples of monumental architecture in the form of dolmen tombs.

Prehistoric Korea

Bronze Age Korean villages were characterised by small semi-subterranean houses built into hillsides. They were either circular or square in design, dug 1.5 metres into the ground, and had thatched roofs. They typically had several hearths and were sometimes protected by wooden fencing. An example of such a village is Hunam-ri near the Han River which has 14 houses and dates to c. 1200 BCE.

Dolmens (in Korean: ko'indol or chisongmyo) - simple structures made of monolithic stones - appear most often near villages, and the archaeological finds buried within them imply that they were constructed as tombs for elite members of the community. 200,000 are known in Korea (with 90% of them in South Korea). They take three forms: the 'table' form where one large stone rests horizontal on two upright stones, one large flat stone set on top of a mound of smaller stones, and a single large stone laid flat above a small buried tomb lined with stone slabs. The first type most often occurs in isolation while the others are sometimes found set in rows or groups. Outstanding examples of ancient Korean dolmens are the table-type structures on Ganghwa Island which date to c. 1000 BCE in the Korean Bronze Age. Single standing stones (menhirs), unrelated to a burial context and perhaps used as marker stones, are also found across Korea.

The Three Kingdoms (4th-7th century CE)

Goguryeo

Unfortunately, there are few surviving public buildings from ancient Korea and no palaces prior to the 16th century CE. However, archaeology and surviving tombs and their wall-paintings have permitted historians to identify the principal characteristics of palace and temple architecture throughout our period. Three Goguryeo-period Buddhist temples have been excavated at Pyongyang, but there are few remains except indications that one had an octagonal pagoda in the centre.

Some of the more substantial surviving archaeological remains from the Goguryeo towns are walls and fortifications from Tonggou, Fushun, and Pyongyang. Tonggou had 8 km of stone wall around the town while Fushun had 2.3 km of wall, which included four gates. Pyongyang, one-time Goguryeo capital, had very large buildings measuring up to 80 x 30 m and palaces with gardens which had artificial hills and lakes. Buildings were decorated with impressed roof tiles carrying lotus flower and demon mask designs which are found in abundance at the sites. In 552 CE a new town was built nearby on the Taesongsan hill with 7 km of fortification walls which had 20 gates and towers as well as various storehouses and wells incorporated into it.

Better survivors than external buildings are tombs, and the earliest Goguryeo ones took the form of stone cairns using river cobbles. However, by the 4th century CE, square tombs were placed within pyramids made of cut-stone blocks. The largest example is at the former capital Gungnaesong (modern Tonggou) and thought to be that of King Gwanggaeto the Great (r. 391–412 CE). 75 metres long and using blocks measuring 3 x 5 metres, it also has four smaller dolmen-like structures at each corner.

Another important tomb is that of Tong Shou, last ruler of Taebang. Located near Pyongyang, an inscription dates the tomb to 357 CE. Its central chamber has 18 limestone columns and wall-paintings; it is surrounded by four smaller chambers. More typical, though, of Goguryeo-period tombs than these two examples are more modest hemispherical earth mounds built over a square base and with an interior tomb of stone. Other architectural features seen in various Goguryeo tombs include corbelled roofing, octagonal pillars, and pivoted stone doors.

Baekje

The art and architecture of the Baekje kingdom are generally considered the finest of the three Kingdoms but, unfortunately for posterity, these have also suffered the greatest destruction thanks to warfare with the Silla, Goguryeo, and Chinese Tang dynasties over the centuries.

The Miruk temple at Iksan had two stone pagodas and one in wood. One stone pagoda survives, albeit with only six of its original 7-9 storeys. The only other surviving Baekje pagoda is also of stone and located at the Chongnim temple at Buyo. Finally, elements of Baekje architectural design can be seen in many surviving wooden buildings in Japan as many Baekje craftsmen went there when Wa Japan was an ally.

Perhaps one of the most impressive tombs from the Baekje kingdom in this period is that of King Muryeong-Wang (r. 501–523 CE) which, within its huge earth mound, has a semi-circular vault lined with hundreds of moulded bricks, many decorated with lotus flower and geometric designs. The structure, located near Gongju, dates to 525 CE, as indicated by an inscription plaque within the tomb.

Silla

Typical Silla tombs of this period are composed of a wooden chamber set in an earth pit which was then covered with a large pile of stones and a mound of earth. To make the tomb waterproof, layers of clay were applied between the stones. Many tombs contain multiple burials, sometimes as many as ten individuals. The lack of an entrance has meant that many more Silla tombs have survived intact in respect to the other two kingdoms and so provided treasures from golden crowns to jade jewellery. The largest such tomb, actually composed of two mounds and containing a king and queen, is the Hwangnam Taechong tomb. Dating to the 5-7th century CE, the tomb measures 80 x 120 m, and its mounds are 22 and 23 m high.

At Gyeongju, the Silla capital has the unique mid-7th century CE Cheomseongdae observatory. 9 metres tall, it acted like a sundial but also has a south-facing window which captures the sun's rays on the interior floor on each equinox. It is the oldest surviving observatory in East Asia.

Unified Silla Kingdom (668-935 CE)

The capital of Gyeongju became even more splendid in this period and is described in the Samgungnyusa collection of texts as having an astonishing 35 palaces, 55 streets, 1360 districts, and 178,936 houses. The palaces had their own gardens and lakes, but all that survives of the buildings themselves are decorative floor tiles. Notable surviving structures at the capital include two surviving stone pagodas – the Dabotap and Seokgatap – which both date to the 8th century CE, traditionally 751 CE. Stone pagodas are Korea's unique contribution to Buddhist architecture, and this pair was originally part of the magnificent 5th-7th century CE Bulguksa temple (Temple of the Buddha Land) which now stands restored but only a fraction of its original size.

One of the outstanding stone structures from the Unified Silla period is the Buddhist Seokguram Grotto temple east of Gyeongju. Constructed between 751 and 774 CE, it contains a circular domed inner chamber within which is a massive seated Buddha. The walls are decorated with 41 figure sculptures set in niches.

From the 7th century CE, Silla tombs became more like the earlier tombs of the Goguryeo and Baekje with a smaller earth mound on top, which was then faced with stone slabs. The slabs are frequently decorated with relief carvings of the twelve animals of the oriental zodiac. Each figure carries a weapon and so offers symbolic protection of the tomb. Two of the finest examples are the tombs of the general Kim Yu-sin (7th century CE) and King Wonseong (8th century CE) at Gwaereung.

Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392 CE)

As already noted, there are no surviving temples from the Goryeo dynasty, made as they were largely of wood, which is a poor archaeological survivor. A good idea of the architectural style is seen in the 13th-century CE Hall of Eternal Life (Muryangsujeon) at the Pusok temple in Yeongju. It is one of the oldest wooden structures surviving in the whole of Korea. Its roof displays a dual edge and is supported by three-tiered supports. It also has the more complex roof brackets at the top of supporting columns typical of the period. The wooden columns taper and permit ceilingless openwork. Stone pagodas have survived better, and these are eclectic depending on location. Some continue the style of earlier periods while others have an octagonal or pentagonal form (influenced by Song China) or a more bulbous shape, perhaps imitating the flat round discs seen in Shamanistic art. Stone lanterns are another indicator of Goryeo architectural design. Many take the form of pairs of lions, columns, or octagonal platforms.

The best-preserved tomb from the Goryeo period is beyond our time frame but, nevertheless, deserves mention and, in any case, continues the architectural traditions of the whole period. Located near Gaeseong, it is that of king Gongmin (r. 1330-1374 CE) and his Mongolian wife Noguk. The two mounds of the tomb have stone balustrades with statues of tigers and sheep, which represent yin and yang. Within the mound are two stone chambers decorated with wall-paintings and constellations on the ceilings. 11th and 12th century CE tombs are also to be found at Gaeseong and are similarly decorated, the animal zodiac occurring in several as it does in Gongmin's tomb.

Architectural Themes

Having considered this long history of architectural development, we can now summarise some of the basic elements and features common to most traditional buildings in ancient Korea. The first decision to be made by Korean architects was where exactly to build their structures. The topography was considered an important factor which could influence the design of a building so that it blended into its local surroundings (pungsu). The best possible place was a site backed by mountains to block the wind and opening onto a wide plain with a river running through it. Both features were thought to provide energy or gi which would flow into the building. Such a location was described as baesan imsu. Also important was to have a pleasant view, the andae, which meant that not only single buildings but sometimes entire villages faced a particular direction.

Construction began with the timber columns (pine was preferred) of the building but these were very often set not directly on the ground but on large stones gathered locally. The use of these stones represented an immediate harmony between the artificial structure and nature, so much so that the stones were not cut but rather the bottom of the wooden column was carved so as to fit exactly over the rough stone. This process is called deombeong jucho. Columns could be round, square, hexagonal or octagonal, although round columns were generally reserved for more important buildings. As in ancient Greek architecture columns were purposely made thinner at the base, thicker in the middle and taller at the corners of the building to make them appear truly straight from a distance, an art known as baeheullim. An additional strategy was to have all the columns lean slightly inwards, a feature called ansollim.

Once the supporting columns were in place, then the rest of the structure was built using wooden beams carefully selected for their strength and with their natural curvature maintained. The Daeungjeon (Main Hall) building at the Cheonynyongsa temple is an excellent example of this approach. Walls were made with earth packed into moulds and about 40 cm thick, or with mud applied to a bamboo framework. Mud was made stronger by mixing in straw and sometimes made waterproof by adding water which had been boiled with seaweed. Windows were made using wooden slats.

Roofs of Korean buildings are typically high-pitched to allow easy drainage of rainwater, which can be heavy in the monsoon season, and strong enough to resist the weight of snow in winter. They are also high to permit air-flow in the warmer months. Ancient roofs were made of wooden beams and then tiled (giwa) over a layer of earth to provide extra insulation. The roofs are concave for aesthetic purposes and the eaves also gently curve upwards (cheoma). This curvature permits extra sunlight in winter to enter the building and at the same time provide a little extra shade in summer.

Finally, many public buildings were enclosed within a wall which carried a small tile roof. The entrance was formed by a tiled-roof gate, sometimes taller than the wall (soseuldaemun) or level with it (pyeongdaemun). The most important temples and palaces often had a triple gate or sammun. Tomb sites usually have a simpler gate (hongsalmun) made of two red columns supporting a row of vertical red beams.

Korean Private Residences - The Hanok

A traditional Korean private home (hanok), or at least those of the upper classes, employed much the same materials as larger Korean public buildings and had similar roofing, but on a smaller scale. The most important structures were, again, timber supporting columns, which defined room space. Between these columns, the external walls were constructed using brick, stone, or earth. Interior walls or temporary room divisions were made using plain sliding paper doors (changhoji) made from mulberry bark. In Korea, only public buildings such as temples, administrative offices, and palaces were permitted to carry colourful wall decoration. External doors and windows were made using interlocking grids of wood (changsal), often carved into highly decorative latticework (kkotsal). The roof was built using wooden beams and then tiled using clay tiles. Roofs could either be in the form of a gable or have overhanging eaves as in public buildings.

A single home often enclosed several inner courtyards and sometimes a garden. There was a separation of living areas for males, females, and servants. Rooms were also divided into functional areas such as hosting guests, sleeping quarters, food preparation, storage, and space for domestic animals. The floors of rooms could be either in wood and slightly elevated (the maru system) to keep the room cool in hot months or used the ondol system of underfloor heating necessary for winter months. This latter type, made of stone with a waxed paper covering, has a system of flues through which hot air flows from the main hearth of the house. It was first employed in the 7th century CE and widely used throughout Korea. Those rooms which were heated in this way had lower paper ceilings while unheated rooms reached the bare roof timbers.

More modest homes for the peasantry were, of course, much simpler affairs than these larger residences having only a few rooms and roofed with thatch (choga), most often using rice straw, laid over a layer of earth spread over wooden boards. Indeed, the presence of roof tiles almost certainly became a status symbol and they were only permitted on the residences of individuals of rank in ancient Korean society.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.