Kosrau I (r. 531-579 CE) was the greatest king of the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) in virtually every aspect of his reign. He reformed the military, the Persian government, expanded his territories, engaged in large-scale building projects, and fostered the development of the arts, sciences, and religion.

He is also known as Khosrow I, Kosrow I, Khosrau I, and by his epithet Anushirvan (“He of the Immortal Soul”). He was the son of King Kavad I (r. 488-496, 498-531 CE) whose efforts had provided him with a formidable military, restrictions on the influences of the nobility, and a stable society. Kosrau I built upon this foundation, expanding the Persian Empire's territories, and encouraging a renaissance in learning and practical application of the sciences which would influence later Muslim Arab and European cultures.

He campaigned against Rome, in the Caucasus, and through northern Arabia, expanding his empire and encouraging cross-cultural exchange, and did the same through his control of a vital section of the Silk Road. The treaties he struck with other leaders concerning trade, as well as the network of roads he had built or repaired throughout his empire, enabled faster and smoother transactions among merchants, which benefited everyone involved.

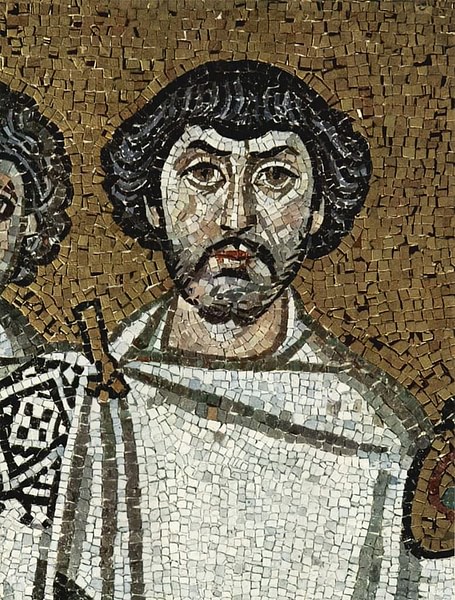

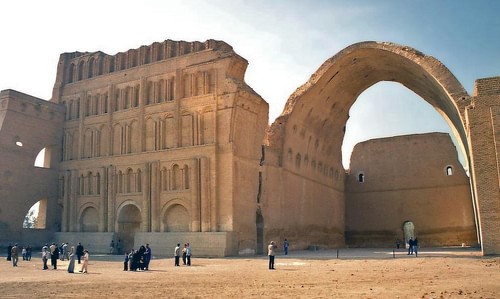

Kosrau I was known to the Greeks as the epitome of Plato's Philosopher King as he was intensely interested in philosophy, inviting scholars and philosophers from India, Greece, Rome, and anywhere else to his court to discuss the subject. When Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) closed the pagan temples and universities in the Byzantine Empire, Kosrau I invited the faculty and priests to his territories and entertained them at his capital at Ctesiphon. He expanded upon the work begun by his predecessors in committing the Avesta (Zoroastrian scriptures) to written form and expanded the intellectual and cultural centers throughout his region. By the time he died, he had raised the Sassanian Empire to the greatest height it would ever know.

Kavad I & Kosrau I's Rise to Power

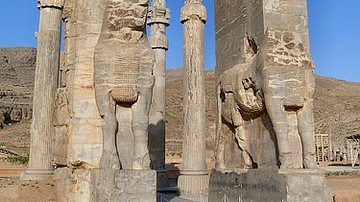

Prior to Kosrau I's reign, the two greatest Sassanian kings were Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE) and Shapur II (r. 309-379 CE). In between those two, the Sassanian kings were almost completely ineffective and, with notable exceptions, the same pattern held between Shapur II and Kavad I.

When Kavad I came to power, he almost instantly established himself as an impressive force in the region, subduing the Khazars who were making incursions into the empire from the Caucasus and defeating them completely by 490 CE. Recognizing that the Sassanian elite and the magi (priestly class) were far too influential in politics, he aligned himself with the religious movement of Mazdakism which had been gaining widespread support among the lower classes since c. 484 CE.

Mazdakism was an early form of communism but founded on religious precepts. The prophet Mazdak believed that everyone – regardless of social class – should share their wealth and possessions equally. He drew on Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism to formulate a religious vision in which simplicity in dress and lifestyle identified a person either with the forces of Good or those of Evil. His teachings challenged the powerful Zoroastrian magi and nobility and threatened to undermine the basic foundations of the Sassanian social hierarchy in challenging the concepts of private property and wealth. Even so, Kavad I recognized they could be a useful weapon against the powerful nobility and Zoroastrian clergy and encouraged the movement.

At this time, the upper class was gathering taxes for its own use and only then passing on what it felt was necessary to the empire's treasury. The Zoroastrian clergy, meanwhile, had become as corrupt and self-serving as the clergy of the Early Iranian Religion Zoroaster himself had opposed c. 1500 BCE. Kavad I instituted tax reforms in keeping with the precepts of Mazdakism, which, naturally, enraged the nobility and clergy, who deposed him and imprisoned him at Anoushbord (the Fortress of Oblivion) and placed his brother Jamasp (r. 496-498 CE) on the throne.

Kavad I escaped his prison and fled to the region of the Hephthalites, married their king's daughter, and returned with a force of over 30,000 to retake his throne in 498 CE. He then continued his previous policies, including support of Mazdakism, to bring the nobility and clergy under control. The Hephthalites, however, although they had assisted him in regaining power and he was married to one of their own, expected him to continue paying them the tribute that had been established under the earlier Sassanian king, Balash (r. 484-488 CE), thereby draining from the treasury whatever had been gained from the nobles. There was nothing Kavad I could do about this, but Kosrau I would bide his time and eventually eliminate the Hephthalite threat completely.

Kosrau I's birthdate is contested (anywhere from c. 500-514 CE) but by 524 CE he was already a dependable military officer in the service of his father. Kavad I, having successfully curbed the power of the nobility and clergy, no longer needed the support of the followers of Mazdak and sent Kosrau I to dispose of them. According to legend, he had Mazdak's followers buried headfirst in an orchard, invited their leader to come see the “rare trees” never seen before, and then executed him by hanging him up for target practice for his archers. When Kavad I died in 531 CE, Kosrau I succeeded him and made the most of the military and economic foundation his father had provided.

Early Reign & Reforms

Kosrau I began his reign by executing his brothers, who contested the succession, along with anyone who supported them. He then made peace with the Byzantine Empire which allowed him space to concentrate on internal reforms. He continued the policies of his father regarding limiting the power of the nobility/clergy and ensured that taxes which formerly enriched both classes now went directly to the imperial treasury.

He also decreed the creation of a new class of nobles – land-owning upper-class citizens not of noble birth – known as deghans. This move reduced the power of the noble families by widening the definition of “noble” and also allowed for these new-nobles to enlist in the elite force of the Savaran Knights, an honor previously restricted to the old aristocratic families, which enlarged his cavalry units.

He further consolidated the government and broke the military into four districts with a separate general in charge of each: Mesopotamia in the west, the Caucasus in the north, the Persian Gulf in the south, and Central Asia in the east. This innovation allowed for each general to respond to threats in their respective region without having to consult with and wait to hear back from a central military high command. He also enlarged the weaponry and improved the armor of the Savaran Knights.

Scholar Kaveh Farrokh notes how one of Kosrau I's most significant military reforms was the creation of “the composite cavalryman whose role was to combine the functions of the horse archers and the regular lance-bearing knights” (231). This formed a separate unit from the more heavily armed and armored cataphracts which allowed for more rapid deployment on the field. Every commander, and each unit, was subject to critical review in terms of professionalism and personal conduct and, unlike in the past, personal merit was rewarded instead of familial connections.

First War with the Byzantine Empire

Kosrau I brokered the Pax Perpetuum (“eternal peace”) with Justinian I at some point between 532 and 535 CE and, not having to concern himself with an outbreak of hostilities, implemented these reforms and consolidated his rule. The “eternal peace” only lasted until 540 CE, however, when Justinian I intervened in the politics of the Caucasus and Mesopotamia. This move alone was not enough to provoke Kosrau I to break the peace but, at this same time, emissaries from the Goths of Italy arrived at his court hoping for his assistance. The great Roman general Belisarius (l. 505-565 CE) was ably crushing Goth resistance in Italy, and a Sassanian offensive, they suggested, would draw Belisarius back east, give them time to regroup, and this would benefit both Goth and Sassanian interests in dividing and draining Byzantine resources.

It does not seem Kosrau I was inclined to help the Goths but the news of Belisarius' victories suggested to him and his High Command that, as soon as Belisarius had defeated the Goths in Italy, he would be sent against the Sassanians on some pretext. In an effort to prevent Justinian I's purported goal of expanding his empire at the Persian's expense, Kosrau I launched a preemptive strike into Syria, taking the cities of Sura and Antioch. He marched on to Apamea and then Chalcis, defeating the Byzantine forces which were hastily deployed against him.

His campaign was a dazzling success and he seemed unstoppable when word came from the northern region of Lazica asking for assistance against Byzantine incursions there. Kosrau I abandoned his Mesopotamian campaign and headed toward Lazica. Ironically, his campaigns – initiated in an effort to strike while the Byzantines were otherwise engaged before Belisarius could be recalled to the region – brought the great general back to assume control of the battered Byzantine army. With Kosrau I in the north, Belisarius easily stopped the Sassanian advance, captured Sisauranon, and sent all prisoners of war to Constantinople to prevent them from taking up arms again.

The success of the Lazic campaign depended on the Sassanians capturing the heavily defended fortress of Petra on the Black Sea (not to be confused with the Nabatean center in Jordan). Kosrau I ordered his engineers to surround the fort with a large ditch, cutting off their supplies, and forcing them to surrender. Kosrau I was orchestrating the same brilliant campaign in Lazica as he had in Mesopotamia when word of Belisarius' victories arrived.

Kosrau I returned from Lazica to deal with the situation but Belisarius was prepared for him. The Sassanian army far outnumbered the Byzantines but, at an initial parley, Belisarius arrived with a contingent of 6,000 men dressed and equipped in order to give the impression that this was a hunting party. Belisarius was hoping that Kosrau I would think the Byzantine force must be enormous, if a mere hunting party was so large, and would abandon his campaign; the plan worked and Kosrau I withdrew from Mesopotamia.

Lazic & Arabian Wars

Kosrau I then entered into negotiations with Justinian I, but the Byzantines, thinking that Kosrau I was bargaining from a position of weakness, ambushed the Sassanians in Armenia and hostilities resumed. The Sassanians crushed the Byzantine forces in Armenia but, in Lazica, the Christian Iberians aligned themselves with the Byzantines and a series of battles were fought between 547-551 CE with each side taking and losing Petra to the other. This ultimately pointless war would continue, with heavy losses on both sides, until a peace accord was reached in 561 CE which stipulated Sassanian withdrawal from Lazica in exchange for an annual tribute paid by the Byzantines.

While Kosrau I had been busy in Mesopotamia and the Caucasus, a situation had developed in Arabia which now required his attention. Toward the end of the reign of Kavad I, the Byzantines had encouraged Christian Abyssinians to invade Arabia, and by c. 526 CE, they held the region around Yemen. By the time the Lazic Wars ended, they had become powerful enough to pose a serious threat to the Sassanian Empire because an attack could now be launched on two fronts – by the Byzantines and Abyssinians – crushing the Sassanians between them. Kosrau I sent his general Vahriz to Arabia who defeated the Abyssinians and claimed their territories for the empire.

Hephthalites, Gok Turks, & Second Byzantine War

The Abyssinian threat neutralized, Kosrau I turned his attention to the Hephthalites and the burden of tribute the Sassanians were still paying. Kosrau I saw an opportunity in the uneasy relationship between the Hephthalites and their neighbors the Gok Turks and initiated an alliance with the Turks to destroy the Hephthalites. The Hephthalites were formidable mounted warriors but, by c. 560 CE, had no central unity. Recognizing they would be unable to mount a defense on two fronts, Kosrau I launched an attack in concert with the Turks and destroyed the Hephthalite forces at the Battle of Gol-Zarriun in 560 CE. The Hephthalite Empire fell, and their lands were divided between the Sassanian Empire and the Turks.

Kosrau I's ambitions, however, drove a wedge between him and the Turks because he required more land and resources to maintain his empire and control of the Silk Road. The Turks were interested in the same goals for themselves and, when Kosrau I made it clear he was unwilling to share resources, the Turks went to the new Byzantine emperor, Justin II (r. 565-574 CE), to broker an alliance against the Sassanians. Justin II refused them but then enacted a policy initiating the same sort of conflict the Turks had proposed.

Armenia had erupted into hostilities between the Christians and Zoroastrians and, hoping to capitalize on the chaos, Justin II reneged on Justinian I's agreement with the Sassanians to maintain defenses in the Caucasus which would open Armenia to invasion. The Byzantines could now intervene in the region claiming it their duty to defend fellow Christians. This action required a Sassanian response – as Justin II must have known it would – and Kosrau I personally led the forces which took the cities of Dara and Nisibis from the Byzantines.

Kosrau I proved himself as capable against Byzantine aggression as before – and now the Byzantines had no Belisarius to save them – and orchestrated another series of brilliant campaigns. Justin II was forced to sue for peace, reinstate the defenses, and pay a large war indemnity. Although peace was restored, hostilities between the Byzantine and Sassanian empires would continue intermittently throughout the rest of Kosrau I's reign.

Conclusion

Although he was forced to spend a great deal of time and effort in Persian warfare, Kosrau I also managed to expand trade, keep a sound economy, initiate building projects, and encourage the development of the arts and sciences. He expanded upon the Academy of Gundeshapur – the great intellectual center and teaching hospital founded in the reign of Shapur I – advancing medical techniques by borrowing and improving upon the works of Egyptian, Indian, and Greek physicians and scholars.

Kosrau I had an avid interest in philosophy, encouraging philosophers of all nations to come to his court at Ctesiphon, and welcomed all those who lost their positions when Justinian I closed the pagan institutions in the Byzantine Empire. According to legend, the game of chess was sent to his court by an Indian monarch - without rules to explain it - and the challenge to either figure out how to play it or pay a fine. Kosrau I, or his courtiers, allegedly worked out the rules and then sent their game of backgammon to India with the same challenge which the unnamed monarch and his court failed to understand and so had to pay the fine. This story, usually told to highlight the intellectual power of Kosrau I and his court, has been repeatedly challenged but clearly suggests how highly he and his administrators were regarded.

He enlarged the defensive walls along the southern border built under the reign of Shapur II but extended this line up along his other borders. He is also credited with enlarging Ctesiphon and the creation of the great archway of Taq Kasra (although this is also attributed to Shapur I). His other building projects included public baths, administrative buildings, fire temples, and canals. His control of the Silk Road through his territories ensured the safety of merchants and the timely delivery of goods that arrived from the east and were then traded with the west, thus encouraging cross-cultural transmission between the different buyers and sellers of various nations.

Kosrau I improved upon the work of Shapur II in committing the Avesta to writing and expanding on its commentary. Although an adherent of Zoroastrianism, he was interested in the views of all religions and philosophies and encouraged religious discussion and debate. Although he swiftly punished apostasy - especially among Zoroastrian clerics – and would not tolerate the socio-religious teachings of Mazdak, he allowed for the development of many different religions throughout his empire and encouraged their expression. By the time his reign, and life, came to an end, he had created the grandest and most complete expression of Persian culture in the ancient world.