The Kristallnacht (Reichkristallnacht, 'Night of Broken Glass', or November Pogrom) was an attack on Jews and Jewish property across Germany and Austria on 9-10 November 1938. Orchestrated as part of a systematic and escalating persecution of Jews by the Nazis, the state-organised pogrom was the beginning of a sharp slide into depravity that terminated in the Holocaust and the murder of 6 million European Jews.

The Nazis & the Jews

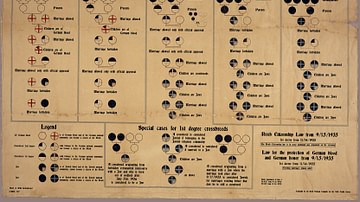

The leader of Nazi Germany Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) was determined to create scapegoats for the ills of the Weimar Republic, created in 1918. A poor economy, weak army, and lack of Germany's prestige abroad were blamed on the Treaty of Versailles (1919) when the victors of the First World War (1914-18) had imposed harsh terms on Germany. Another Nazi scapegoat was the Jews living in Germany. As far back as his book Mein Kampf, published in 1925, Hitler had identified the Jews as a group which he considered was holding Germany and the pure Aryan Volk (people) back from their true potential. Hitler and the Nazis were determined to force Jews into emigrating, firstly by petty humiliations and confiscating property, and then by more direct and physical persecution. Jews were broadly identified by the restrictive 1935 Nuremberg Laws as any person with three or four Jewish grandparents, but ever since 1933, the Nazis had been systematically removing Jews from small villages and towns, moving them into the cities. Emigration was actively encouraged, although the state often seized assets and only let the departing take the minimum of possessions. Jews were forbidden from holding government and official administrative positions and suffered many other discriminations in daily life. By 1938, half of Germany's 500,000 Jews had emigrated, and the number of Jewish businesses in Germany had shrunk from 50,000 (1933) to 9,000. For Hitler, this was not enough. The ominous steps to a violent solution to what Hitler described as 'the Jewish Question' (Judenfrage), began with the Kristallnacht.

The Pretext for Kristallnacht

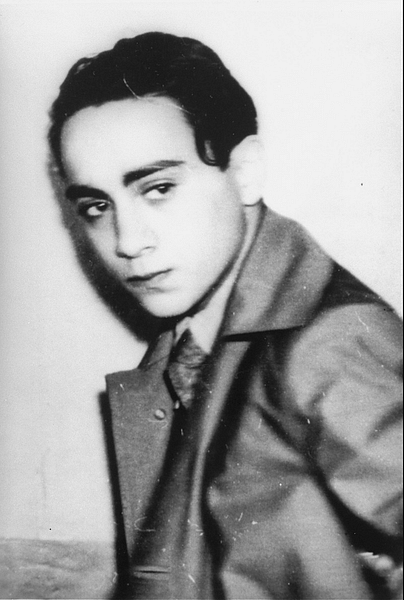

In many Nazi campaigns against their enemies, a pretext was found, an incident which was exploded out of all proportion to its original significance by the Nazi minister of information and propaganda, Joseph Goebbels (1897-1945). The Polish government had ruled in mid-1938 that any Polish Jews living abroad had to go through several difficult rounds of bureaucracy if they were to maintain their Polish citizenship. Germany then had around 25,000 Polish Jews within its borders, and, rather than have them become stateless, Hitler decided to forcibly expel around 17,000 of them. Poland refused to accept these people, and so they lived in border camps with no rights from either state. Herschel Grynszpan, whose Jewish parents had been expelled in this way, decided to make a dramatic protest about their persecution. Grynszpan, who was born and raised in Germany but lived in Paris at the time, went to the German embassy and there shot the third secretary Ernst von Rath on 7 November 1938. Secretary von Rath died of his wounds on 9 November.

Goebbels seized upon the Grynszpan incident, which happened to be the 15th anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch (Hitler's failed coup d'etat), to justify further oppression of German Jews. The timing was also right for Goebbels personally, as he had not yet recovered from a personal scandal involving an actress, and the remnants of the SA (Sturmabteilungen or Stormtroopers, better known as the Brownshirts for their uniform), the early Nazi paramilitary unit purged by Hitler in 1934, were itching for something violent to do. Goebbels made an inflammatory speech and secretly sent out orders for a violent reaction on the streets to the Grynszpan incident. The practical organiser of the attacks on the Jews was Reinhard Heydrich (1904-1942), head of the Security Service (SD) and second only to Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945) in the SS (Schutzstaffeln), the other Nazi paramilitary unit involved in the pogrom. Heydrich telephoned around to local SA, SD, and SS groups, as well as the local police. The official line would later be that the riots had occurred 'spontaneously', carried out by ordinary people who had had enough of the Jews. Only after the Second World War (1939-45), when secret German documents were captured, was the truth revealed. This had been a state-sponsored attack, and one that Adolf Hitler was fully aware of (at the time, both the Nazi leader and Goebbels dissociated themselves from the events through their public silence). Below are extracts of the orders sent out by Heydrich:

a. Only such measures should be taken which did not involve danger to German life or property. (For instance synagogues are to be burned down only when there is no danger of fire to the surroundings.)

b. Business and private apartments of Jews may be destroyed but not looted…

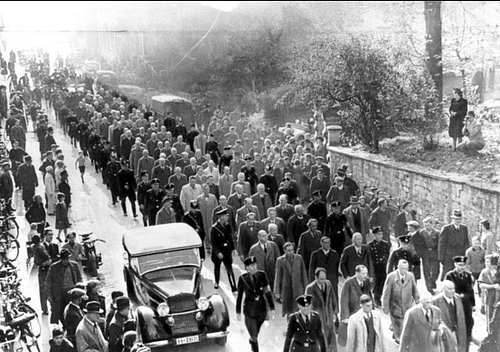

d. The demonstrations which are going to take place should not be hindered by the police…As many Jews, especially rich ones, are to be arrested as can be accommodated in the existing prisons…Upon their arrest, the appropriate concentration camps should be contacted immediately, in order to confine them in these camps as soon as possible…(quoted in Shirer, 430-1)

The Night of Broken Glass

On the night of 9 November, and in some areas in the following days and nights, Nazi thugs targeted Jewish areas of cities and towns across Germany and Austria. Over 1,000 synagogues were attacked, 267 of which were wrecked beyond repair or burnt to the ground. 7,500 shops, including 31 large department stores owned by Jews, had their windows smashed (hence the Kristallnacht name) and their goods, contrary to the orders, looted. Jewish homes were burnt down, and Jewish schools, hospitals, and cemeteries were vandalised. Countless Jews were beaten up in the streets by gangs of thugs, mostly Nazis out of uniform and carrying such crude weapons as pieces of lead piping. According to the official records, 91 Jews were killed in the attacks, but the real figure was likely much higher. A significant number of Jews who had lost everything subsequently committed suicide.

Hugh Greene, a British newspaper journalist, recalls what he saw of the Kristallnacht:

I was in Berlin at that time and saw some pretty revolting sights – the destruction of Jewish shops, Jews being arrested and led away, the police standing by while the gangs destroyed the shops and even groups of well-dressed women cheering.

(Holmes, 42)

The Nazi architect and minister Albert Speer (1905-1981) recalls the scenes in Berlin the day after the pogrom:

On November 10, driving to the office, I passed the smoldering ruins of the Berlin synagogues…what really disturbed me at the time was the aspect of disorder that I saw on Fasanenstrasse: charred beams, collapsed façades, burned-out walls – anticipations of a scene that during the war would dominate much of Europe…I did not see that more was being smashed than glass, that on that night Hitler had crossed a Rubicon…had taken a step that irrevocably sealed the fate of his country…Later, in private, Goebbels hinted that he had been the impresario for this sad and terrible night.

(169-70)

In these few terrible days, 35,000 Jews were arrested and taken to concentration camps prior to their expulsion from German territory. The fortunate ones got away with losing all their property for "as many as a thousand Jews died in concentration camps in the following six months" (Dear, 287) due to the hard labour, unsanitary conditions, malnutrition, beatings, and executions. Very few of the attackers were prosecuted, and of those which were, the courts very often dismissed their cases.

Non-Jews were obliged to be complicit in the attacks through their silence, even if many now realised the mask of respectability uneasily worn by the Nazi regime had finally been removed. Merely commenting on the attacks in public could lead to investigation and even imprisonment by the Gestapo, Germany's secret police. Emmy Bonhoeffer recalls the fate of her brother-in-law:

I remember that the husband of my sister Lena, when he went in the morning after the day of the Kristallnacht, he went by train to his office downtown and he saw that the synagogue was burning and he murmured, "That is an insult for cultured people, an insult to culture." Well, right away a gentleman in front of him turned and showed his Party badge and took out his papers. He was a man of the Gestapo and my brother-in-law had to show his papers, to give his address and he was ordered to come to the Party office next morning at nine o'clock…his punishment was that he had to arrange and to distribute the ration cards for the area beginning of each month for years, until the end of the war.

(Holmes, 42)

The Reaction Abroad

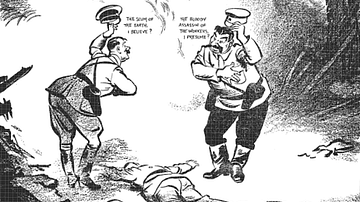

The reaction abroad to the Kristallnacht was one of horror. US President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) stated that he thought such a thing "could not happen in the twentieth century" (McDonough, 78). The US ambassador to Germany was called home in protest. "Practically no American newspaper, irrespective of size, circulation, location, or political inclination failed to condemn Germany" (Friedländer, 299). In Britain, the House of Commons condemned the attacks, and an opinion poll revealed that 70% of the population was shocked at the attack and wanted to cut off diplomatic relations with Nazi Germany (already under deep suspicions over crises like the Anschluss and German occupation of the Czech Sudetenland). Many now questioned if the policy of appeasement, which had culminated in the Munich Agreement of September 1938, was morally valid when dealing with such an unprincipled state.

Further Controls on Jews

Meanwhile, the German state began to further restrict the liberty of Jews. To meet the tremendous costs of repairs after the Kristallnacht, Jewish communities received enormous collective fines, and the insurance payouts were confiscated by the state. Jewish children were not permitted to return to school, and curfews were imposed. Jews could not attend cinemas or travel with non-Jews on trains, they were not permitted to own a car, buy cigarettes, or enter public parks. Jewish property continued to be confiscated on a large scale. Jewish businesses and the Jewish press were systematically closed down and then prohibited. Seemingly random imprisonments and transportation to labour camps became more and more common. As M. Chalmers, the translator of the diary kept by the Jewish university lecturer Victor Klemperer throughout this period, remarks:

The point at which some kind of normal life, under the conditions of a racist dictatorship, becomes impossible is the November 1938 pogrom ("Kristallnacht")…The pogrom is at once the peak and conclusion of mob violence against Jews…It is the point at which Jews realize that there is no one and nothing to protect them.

(xiv)

Unsurprisingly, Jews across German territories now emigrated in even larger numbers than before, 100,000 from Austria alone. In Germany, "by 1939, three hundred thousand Jews, broadly speaking the younger section of the community, had emigrated" (Stone, 89). The loss to Germany came in all areas of life as writers, musicians, doctors, and scientists left en masse. Such was the movement of people that many states began to pass laws that restricted immigration, Jews in particular. Tragically, though, tens of thousands of migrant Jews, who thought they had reached safety, only found themselves in any case under Nazi rule following the occupation of Western Europe during WWII. Rounded up in ghettos, much worse was to come as the Nazis and their allies began to systematically murder Jews (and other "undesirables" ranging from those with disabilities to Romani people) in secret death camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau. Ultimately, The Nazi's "Final Solution" resulted in the Holocaust, that is the murder of six million European Jews.