Lascaux Cave is a Palaeolithic cave situated in southwestern France, near the village of Montignac in the Dordogne region, which houses some of the most famous examples of prehistoric cave paintings. Close to 600 paintings – mostly of animals – dot the interior walls of the cave in impressive compositions. Horses are the most numerous, but deer, aurochs, ibex, bison, and even some felines can also be found. Besides these paintings, which represent most of the major images, there are also around 1,400 engravings of a similar order. The art, dated to c. 17,000 to c. 15,000 BCE, falls within the Upper Palaeolithic period and was created by the clearly skilled hands of humans living in the area at that time. The region seems to be a hotspot; many beautifully decorated caves have been discovered there. The exact meaning of the paintings at Lascaux or any of the other sites is still subject to discussion, but the prevailing view attaches a ritualistic or even spiritual component to them, hinting at the sophistication of their creators. Lascaux was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Sites list in 1979, along with other prehistoric sites in its proximity.

The discovery

On 12 September 1940 CE four boys examined the foxhole down which their dog had fallen on the hill of Lascaux. After widening the entrance, Marcel Ravidat was the first one to slide all the way to the bottom, his three friends following after him. After constructing a makeshift lamp to light their way, they found a wider variety of animals than expected; in the Axial Gallery they first encountered the depictions on the walls. The following day they returned, better prepared this time, and explored deeper parts of the cave. The boys, in awe of what they had found, told their teacher, after which the process towards excavating the cave was set in motion. By 1948 CE the cave was ready to be opened to the public.

Occupation by humans

Around the time Lascaux cave was decorated (c. 17,000 to c. 15,000 BCE), anatomically modern humans (homo sapiens) had been well at home in Europe for a good while already, since at least 40,000 BCE. Following the archaeological record, they seem to have been abundantly present in the region between southeastern France and the Cantabrian Mountains in the north of Spain, which includes Lascaux. The cave itself shows only temporary occupation, probably linked to activities related to creating the art. However, it is possible that the first couple of metres of the entrance vestibule of the cave – the space the daylight could still reach – might have been inhabited.

From the finds originating from the cave, we know that the deeper parts of the cave were lit by sandstone lamps that used animal fat as fuel, as well as by fireplaces. Here, the artists worked in what must have been smoky conditions, using minerals as pigments for their images. Reds, yellows, and blacks are the predominant colours. Red was provided by hematite, either raw or as found within red clay and ochre; yellow by iron oxyhydroxides; and black either by charcoal or manganese oxides. The pigments could be prepared by grinding, mixing, or heating, after which they were transferred onto the cave walls. Painting techniques include drawing with fingers or charcoal, applying pigment with 'brushes' made of hair or moss, and blowing the pigment on a stencil or directly onto the wall with, for instance, a hollow bone.

The catch is that there are no known deposits of the specific manganese oxides found at Lascaux anywhere in the area surrounding the cave. The closest known source is some 250 kilometres (155 miles) away, in the central Pyrenees, which might point to a trade or supply route. It was not uncommon for humans living around that time to source their materials a bit further afield, tens of kilometres away, but the distance in question here may indicate that the Lascaux artists put in a superb amount of effort.

Besides the paintings, many tools were found at Lascaux. Among these are many flint tools, some of which display signs of being used specifically for carving engravings into the walls. Bone tools were also present. The pigments used at Lascaux contain traces of reindeer antler, most likely introduced either because antler was carved right next to the pigments or because it was used to mix the pigments into water. The remains of shellfish shells, some of them pierced, tie in well with other evidence of personal adornment found among humans living in Europe during the Upper Palaeolithic.

The art

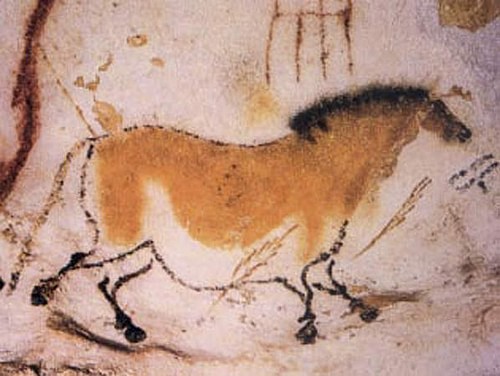

The art at Lascaux was both painted on and engraved into the uneven walls of the cave, the artists working with the edges and curves of the walls to enhance their compositions. The resulting impressive displays depict mainly animals, but also a significant amount of abstract symbols, and even a human. Of the animals, horses dominate the imagery, followed by deer and aurochs, and then ibex and bison. A few carnivores, such as lions and bears, are also present. The archaeological record of the area shows that the depicted animals reflect the fauna that was known to these Palaeolithic humans.

The entrance of the cave leads away from the daylight and straight into the main chamber of the cave, the Hall of the Bulls. Aptly named, this space contains mostly aurochs, a now-extinct type of large cattle. In a round dance, four large bulls tower above fleeing horses and deer, the relief of the walls serving to emphasise certain parts of the paintings. The animals are shown in side-view, but with their horns turned, giving the paintings a liveliness indicative of great skill. So far, these animals are easily identifiable, but others are less clear-cut. See, for instance, the seemingly pregnant horse with what looks like one horn on its head. Another mysterious figure is depicted with panther skin, a deer's tail, a bison's hump, two horns, and a male member. Creative minds have suggested it may be a sorcerer or wizard, but what it really represents is hard to determine.

Beyond the Hall of the Bulls lies the Axial Gallery, a dead-end passage, but a spectacular one at that. It has been dubbed the 'Sistine Chapel of Prehistory,' as its ceiling is home to several eye-catching compositions. Red aurochs stand with their heads forming a circle, while the main figures of the Gallery stand opposite one another: a mighty black bull on one side, a female aurochs on the other, seemingly jumping onto some sort of lattice that has been drawn underneath her hooves. There are horses in many shapes, including one known as the 'Chinese horse,' with its hooves depicted slightly to the back, demonstrating a use of perspective far ahead of its time. Towards the back of the passage, a horse gallops with its mane blowing in the wind while its companion falls over with legs in the air.

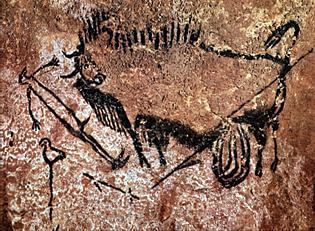

A second exit from the Hall of the Bulls leads to the Passage, which houses mostly engravings but also some paintings of a large variety of animals. In the Nave, following the Passage, a large black bull as well as two bisons stand out because of their wild power, seemingly fleeing. Opposite, a frieze shows five deer who appear to be swimming. After the Nave, the Chamber of Felines throws some predators into the mix, with engravings of lions dominating the room. In another branch of the cave, the room known as the Shaft adds some more material for discussion. Here, besides the wounded bison with its intestines sprawling out from its gut, are a woolly rhinoceros, a bird on what might be a stick, and a naked man with an erect member. This image clearly tells a story, although it is hard to be certain exactly what that story might be.

The cave today

The original cave was closed to the public in 1963 CE after it became clear that the many visitors caused, among others, the growth of algae on the cave walls, dealing irreparable damage to the paintings. Despite the closure, fungi have spread within the cave, and efforts to control these issues and protect the art are ongoing. Those looking for an alternative experience can visit Lascaux II, a replica of the Great Hall of the Bulls and the Painted Gallery sections, which was opened in 1983 CE and is located a mere 200 metres from the original cave.