The League of Nations was founded in January 1920 to promote world peace and welfare. Created by the Treaty of Versailles, which formally ended the First World War (1914-18), the League provided a forum where nations promised to resolve international disputes peacefully. Any state that attacked another would be subjected to the collective action of all the other members, first in the form of economic sanctions, and if necessary, military action.

The League's members met annually in Geneva, Switzerland, in a general assembly and, for the most powerful members only, more regularly in meetings of an executive council. Although some progress was made in terms of limiting armaments and promoting citizen welfare, the League proved ineffective against acts of aggression by Italy, Japan, and Germany. The weaknesses of the League were one of several causes of WWII (1939-45), but the idea of international cooperation survived the conflict to be reborn in the form of the United Nations.

Foundation

The Treaty of Versailles, signed on 28 June 1919, imposed peace terms on Germany and formally ended WWI. The treaty limited Germany's armaments, redistributed important areas of German territory and colonies, and stipulated that Germany must pay war reparations and accept responsibility for WWI. The treaty also formed a new international body to facilitate global diplomacy and help foster a lasting peace: the League of Nations.

After the horrors of WWI, when 7 million people were killed and 21 million seriously injured, the victors – Britain, France, the United States, and Italy – sought to guarantee no such global conflict ever happened again.

The prime mover for the establishment of the League was US President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924). Wilson had come up with 14 points for a new world in the summer of 1918. The president identified certain causes of WWI he wanted never to replicate: self-interested and secretive diplomacy, the repression of minority groups within empires and larger states, and autocratic regimes ignoring their own people's wishes. A new international organization was required that would eradicate these three diseases of world diplomacy and champion instead democracy, self-determination, and openness. Although Wilson's emphasis on self-determination was not applied to WWI's losers or the nationals caught up in a massive redrawing of the maps of Europe, Africa, and East Asia, the League of Nations became a reality in January 1920.

Purpose

The League of Nations' primary purpose was expressed in Article 10 of its 26-article Covenant:

To respect and preserve as against external aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all Members.

(Dear, 528)

Assuming diplomatic means had failed, any member found guilty of aggression against another's territory would be subjected, according to Article 16 of the Covenant, first to economic sanctions and then, if required, to military sanctions. These sanctions would be conducted collectively by all the other members. It was hoped that this idea of ‘collective security' would be a powerful deterrent to any would-be aggressor.

The League would act as a neutral arbitrator between disputants over territorial issues. In a spirit of open diplomacy, all treaties would be scrutinised by the League to check that they did not threaten global peace. The League could also send disputes for consideration to the newly established Permanent Court of International Justice in The Hague. Another aim of the League was to help reduce world armaments since it was felt that one of the causes of WWI had been the arms races between certain nations. Other aims included the fostering of international cooperation in economics and social matters, particularly in the fields of health and communications.

While everyone, at least publicly, endorsed these lofty aims, there remained some disagreements amongst nations as to the details of the League's mission. For example, Japan called for the League's covenant to include a clause regarding racial equality, but the idea was rejected. It was also true that some members undermined the promises of Article 10 by forming their own international alliances and pacts of mutual assistance. As we shall see, when the League was tested by an aggressive nation, its members were, unfortunately, far from unified in their response.

Structure & Organization

The first members of the League of Nations were the 32 allied victors of WWI plus 12 other neutral states. Losers of WWI (and the USSR, then widely regarded as a revolutionary state) had first to prove they would adhere to the new raft of post-war treaties before they were allowed to apply for membership. The members of the League sent delegates, typically their foreign ministers, to meet each September in the Assembly at its headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland. All members had equal rights in the Assembly. More regular meetings (usually four per year) were held by a council of the most powerful members, which included Britain, France, Italy, and Japan, the four holders of permanent seats on the council (Germany also gained a permanent seat from 1926). Four (later increased to six and then nine) other council members were voted in by the Assembly. Each council member had a veto vote. A Secretariat looked after the League's expenses, which were not extravagant since most experts involved with the League's operations only had their expenses paid. Open committees, in which all members could participate and vote, carried out the detailed day-to-day work of the League, their conclusions then being presented to the Assembly for approval. Decisions were passed when voted unanimously by the Assembly, which was usually achieved since disagreeing members tended to abstain.

The membership of the League was crucial to its success or failure. Due to domestic politics, the isolationists won the day at home, and the United States chose not to join the League from the start, a great blow to its ambitions. Germany, still not trusted, was not permitted to join immediately, only joining the club in 1926 (and leaving again in October 1933). The USSR joined in July 1934, and then only because Germany had left, but was expelled in 1939. Japan left the League in 1933 ad Italy in 1937. Further instability to membership came from new members being added and others disappearing when they ceased to exist after foreign invasion. This instability in membership became a serious weakness.

Mandated Territories

One of the duties of the League of Nations besides trying to keep international peace was to administer those territories which had changed ownership as a consequence of the post-war treaties dealing with WWI's losers. Territories which had once belonged to Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire were redistributed, either gaining full independence (e.g. Iraq) or put in the care of WWI's victors (e.g. Palestine, Syria, and the Cameroons). These territories were regarded as "League Mandated" territories and received regular inspections by the League, although, in practice, they were often regarded as simply new colonies by their administrating nations. As the historian F. McDonough remarks, "the fig leaf of a League of Nations mandate hid old-fashioned imperial gains" (53).

Germany's coal-rich Saar region was given to the League of Nations to manage, with a plebiscite promised at an unspecified future date. Danzig (Gdańsk) was made an autonomous Free City controlled by the League of Nations. These mandates and settling minor territorial disputes kept the League busy in its first years, but a serious challenge to its authority was just over the horizon.

The Corfu Crisis

The first significant challenge to the fragile authority of the League was made by the fascist leader of Italy, Benito Mussolini (1883-1945). Mussolini was on the lookout for cheap propaganda victories, which would bolster his popularity at home, where the economy was not doing well. The first of these propaganda coups was the Corfu incident, as it became known, which occurred in 1923. Italy occupied the Greek island of Corfu, the pretext being the assassination of an Italian general in Greece. The League proved itself incapable of arbitrating the crisis when it was let down by the principal world leaders who decided not to act against Mussolini's aggression. Nevertheless, the League was not entirely impotent, and its debates and resolutions did create an atmosphere of international disapproval that ultimately persuaded Mussolini to hasten his withdrawal from Corfu.

The Manchuria Crisis

A more serious challenge to the League's power came when Japan occupied Manchuria (which they called Manchukuo) in September 1931. Japan was pursuing dreams of an empire, just like Italy. Manchuria, a region of north-east China rich in natural resources and with a geographical position of strategic importance, had long been coveted by both the USSR and Japan. There was, too, a sizeable Japanese minority in the region, and the Chinese government's control of the area was weak. The pretext for the invasion by Japan's Kwantung (Guangdong) Army was the blowing up of a section of the South Manchurian Railway, then controlled by Japan. Japan claimed China had been responsible for the attack. Known as the Manchurian incident or Mukden incident, the Japanese army had themselves sabotaged the line. A Japanese puppet state, Manchukuo, was established in March 1932. China appealed to the League for help.

The members of the League could not agree on economic or military sanctions against Japan. The League did refuse to recognise Manchukuo as an independent state, but an economic response (never mind a military one) could not find sufficient support amongst key League members, everyone being reluctant to limit trade during a world economic crisis. The League eventually found Japan the aggressor, and an investigative commission advised the return of the territory to China. Japan did not agree and renounced its membership in March 1933. This was perhaps just as well since the country fell even lower in the esteem of League members when it started an all-out war with China in the so-called China incident of July 1937.

The Abyssinia Crisis

Mussolini defied the League for a second time when he decided to invade Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia) in October 1935. Italy already had some colonies in Africa, and Mussolini dreamed of expanding his empire. Abyssinia, an independent nation but without a modern army, was a relatively easy target for Italian mechanised forces moving in from the neighbouring Italian colonies of Eritrea and Italian Somaliland. An attack on Abyssinia offered only the prestige of conquest and revenge for the Italian defeat there back in 1896 since it had very little wealth and even less strategic value. Mussolini, as with Corfu, hoped for a powerful propaganda effect without incurring high costs. The fascist leader was only half successful since his escapade in East Africa turned into a major drain on his already weak domestic economy. Further, the League members (of which Abyssinia was one) this time agreed to impose economic sanctions on Italy, banning the sale of arms and raw materials, and loans.

Although 52 members of the League opposed Mussolini's invasion, neither France nor Britain were interested in starting a war with Italy over Abyssinia, already considered an Italian sphere of influence before the invasion. No military action was taken. Significantly, too, oil remained a conspicuous omission from the ineffective economic sanctions.

Another blow to the League came from within. The Hoare-Laval pact of December 1935 was a supposed-to-be secret agreement between Britain and France, which, although never formally signed, undermined the League by accepting the invasion of Abyssinia as an accomplished fact. By March 1936, the Italians had defeated the Abyssinians, and their emperor Haile Selassie (r. 1930-74) fled into exile. Some Abyssinians, nevertheless, continued to resist the occupation, which was characterised by brutal repression. The League cancelled its economic sanctions in July 1936.

After the Abyssinia crisis, the League receded into the background of foreign diplomacy. As the historian A. J. P. Taylor puts it: "The League continued in existence only by averting its eyes from what was happening around it" (128). Individual members now concentrated not on collective security but on making their own treaties.

Britain and France had been particularly anxious not to drive Mussolini into an alliance with fellow fascist leader Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) in Germany. Through 1935, there was still a chance Italy might aid Britain and France against any future aggression by Germany in Europe, as indicated by Mussolini's promise to send nine divisions to defend France if attacked by Hitler. Mussolini, playing the powers off against each other, would only reveal his true intentions when he signed a full military agreement with Hitler in May 1939.

Hitler & Appeasement

The lack of a meaningful reaction from the League to international aggression was duly noted by Hitler. Germany had long called for equality with the other great powers in terms of armaments. In 1933, Germany withdrew from the League over the issue. All the ills of the Weimar Republic (1918-33), its high inflation and unemployment, lack of stature in world diplomacy, and inferior arms compared to other nations were blamed on the Treaty of Versailles and, by association, the League of Nations. The decision to leave was ratified both by a plebiscite in Germany and a vote in the Reichstag parliament.

As the historian J. Dülffer notes, "Hitler's decision to withdraw from the League marked an important, fundamental change: a rejection of a policy based largely on multilateral obligations in favour of one of power politics and national egoism" (58).

At the same time, Hitler was giving out confusing messages that he desired disarmament and world peace. The German leader signed a non-aggression pact with Poland in January 1934 and even promised to return to the League of Nations. It is interesting to note that Poland, in signing the pact, was demonstrating its belief that the League was not in a position to give practical aid to victims of aggression.

In 1935, Germany admitted its armed forces were four times larger than the Treaty of Versailles permitted. Hitler reoccupied the demilitarised Rhineland in March 1936. The League offered no response to the reoccupation, which was, after all, only Germany 'taking control of its own back garden', a phrase coined by the British Times newspaper.

Hitler's main opponents were divided. Indeed, Britain and France had long diverged on the very purpose of the League. Britain wanted it to operate as a theatre of international conciliation; France wanted it to be used as a defence against Germany. Britain signed a naval agreement with Hitler in 1935 to limit Germany's navy (but allow it a bigger one than Versailles had permitted) while France, outraged at this, signed a mutual aid treaty with the USSR in March 1935, should either be attacked by Germany. The Abyssinia crisis also brought a divided response from Britain and France, the two nations that should have been working most closely together. Above all, nobody at the League wanted another continent-wide war. With most of the major nations unprepared psychologically and militarily for war, appeasement became the watchword of their diplomats, but delay seemed the only realistic objective. As the prospect of war loomed ever larger on the horizon, many members were keen to disassociate themselves from the League and its obligation for a collective security response to invasions by Japan, Italy, Germany or anyone else.

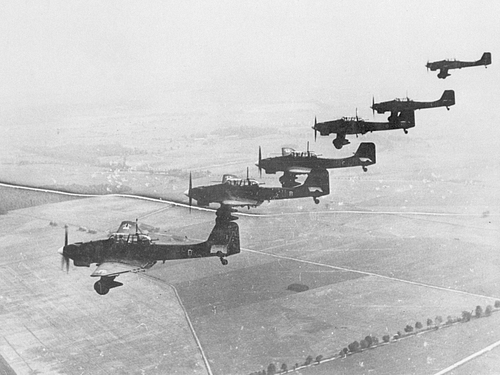

In October 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out, with both Italy and Germany directly involved. The US was ominously silent. The aggressor states began to sign mutual assistance treaties. From July 1937, China was at war with Japan. Hitler joined Austria to Germany with the Anschluss in March 1938. In the Munich Agreement of September 1938, Germany was permitted to take the Sudetenland. In March 1939, German soldiers marched into Czechoslovakia. In April, Mussolini occupied Albania. In August, Germany and the USSR signed a military alliance. So the tide of crises pushed the League to the back shores of world diplomacy while individual states struck out on their own private courses to survive the winds of war as best they could. Planes, tanks, and artillery were deciding international borders now, not diplomats. The invasion of Poland in 1939 by Hitler finally brought a formal declaration of war from Britain and France on 3 September. The very disaster the League had been founded to avoid had come to pass.

Legacy

The League may have failed to prevent the Second World War, but it had, at least, provided a forum where those who worked for peace could call attention to the futility of conflict. The League had also achieved some progress in promoting people's general welfare worldwide through the International Labour Organisation (which still exists today), promoting social fairness, improving working conditions, and reducing colonial exploitation, all in a period when openly debating such issues was itself a form of progress. Other League successes included improving the rights and welfare of many minority groups, women, and refugees, as well as health and education levels.

The League of Nation's functions were certainly not helped by certain members excluding themselves, others attacking fellow members in wilful disregard of the League's articles, and the Great Depression of 1929, which put great stress on societies and traditional political institutions. The League had demonstrated the usefulness of a debating chamber for non-military international issues of all kinds, and so it was, despite its difficulties and its suspension for the duration of WWII, a forerunner of today's United Nations, which was formed in the summer of 1945. The League of Nations was formally terminated in April 1946, and its treaties and assets were passed on to the UN, which, with an entirely new constitution and a much larger membership, continues to meet the challenges of a world composed of largely self-interested nations.