The Lebor Gabála Érenn or The Book of the Taking of Ireland, is a pseudo-historical collection of poetry and prose narrative which was first compiled in the 11th Century CE. The Lebor Gabála centers around an origin myth which describes the settlement of Ireland and its history from the Biblical Flood narrative to the Middle Ages. Considered by scholars to be a highly fictionalized and unreliable account of ancient Irish history, the Lebor Gabála Érenn combines elements of Christian narrative with surviving threads of oral history and Irish mythology. Comprised of about ten books, several versions and passages of the Lebor Gabála Érenn are extant

Background of the Lebor Gabála Érenn

More than being an accurate retelling of ancient Irish historical traditions, the Lebor Gabála Érenn served the purpose of creating an epic Biblical origin story for the Irish that was comparable to that of the Israelites. The Lebor Gabála Érenn was likely heavily influenced by Medieval historical works like St. Augustine's 5th Century CE The City of God and Orosius' roughly contemporary Histories. The Lebor Gabála Érenn also served a secondary political purpose of providing 12th Century CE Irish nobility with an ancient Spanish pedigree at a time when Spain and Ireland had a close relationship.

In addition to elements of Biblical narrative like the Great Flood and the descendants of Noah, the Lebor Gabála Érenn includes obvious elements of pre-Christian Irish mythology. The most prominent examples include the Fomorians, the hostile or chaotic gods of Irish mythology, and the Tuatha Dé Dannan, the Irish gods of civilization and growth. However, modern scholars have identified many other elements of the Lebor Gabála Érenn as remnants of earlier Irish myths.

The First three Takings of Ireland

The Lebor Gabála Érenn describes six invasions or “takings” of Ireland, in which the island is colonized by different peoples. These six invasions may have been inspired by the Medieval Christian tradition of dividing history into the Six Ages of the World. The first four waves of settlers are all either killed or expelled from Ireland over the course of the epic, leaving Ireland to the Gaels, and the Tuatha Dé Dannan.

The first settlers of Ireland are Cessair, daughter of Noah, and her followers who sailed to the western edge of the world in order to escape the Great Flood. Out of the expedition, 50 women, including Cessair, survive the journey but all except three of the men are killed. To settle this gender imbalance, each of the men took 16 wives but soon two of the men perish, leaving Fintan mac Bóchra as the only man left in Ireland. Overwhelmed, Fintan flees and is turned into a hawk. Fintan survives in his hawk form for 5,500 years and uses his great wisdom to advise the kings of Ireland down to the time of the legendary Finn mac Cumhaill and the Christianization of Ireland in the 5th Century CE.

The second wave of settlers arrive some three centuries after the Flood, led by Partholón, one of the descendants of Noah through Magog and Japheth. These settlers meet with tragedy, and all 9,000 of Partholón's followers are described as succumbing to plague within a week, leaving Ireland uninhabited until the arrival of Nemed 30 years later.

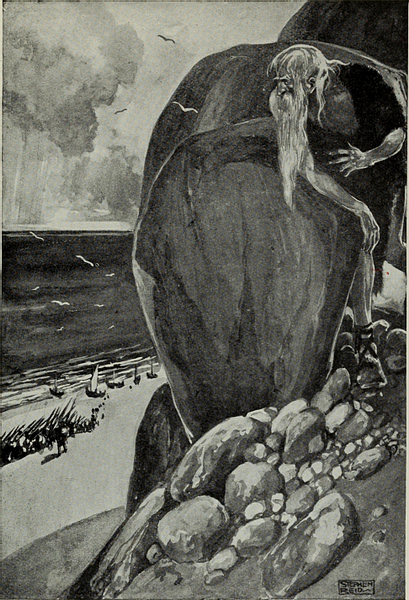

The Lebor Gabála Érenn identifies Nemed as a Scythian, who leads yet another doomed group of settlers to Ireland. These followers of Nemed soon find themselves contending with the Fomorians, dark deities from Ireland's murky past. The Lebor Gabála Érenn describes the Nemedians defeating the Fomorians in several battles before eventually being subjugated. The triumphant Fomorians force the Nemedians to offer up two-thirds of their grain, their milk, and their children on the annual occasion of Samhain. A bloodbath on both sides ensues when the oppressed Nemedians rise up, and only 30 men survive, some sailing to Britain, others to Greece, and some to the far north.

THE CONTENDINGS OF THE TUATHA DÉ DANNAN & THE FIR BOLG

The descendants of Nemed who fled to Greece after the doomed rebellion against the Fomorians eventually return some 200 years later. This fourth wave of colonizers are known as the Fir Bolg, and were said to have been enslaved by the Greeks before they departed for Ireland around the time of the Israelite's Exodus from Egypt according to the Bible.

37 years later come the arrival of the fifth wave of conquerors in the Lebor Gabála; the Tuatha Dé Dannan. The Tuatha Dé Dannan arrive in dark clouds of fog, and the Lebor Gabála Érenn claims that it was not even clear whether the Tuatha Dé Dannan had arrived from heaven or earth, but that they possessed powerful magic. The Tuatha Dé Dannan demand half of the island, but the Fir Bolg refuse and are wiped out in the ensuing struggles.

So that they were the Tuatha De Danann who came to Ireland. In this wise they came, in dark clouds. They landed on the mountains of Conmaicne Rein in Connachta; and they brought a darkness over the sun for three days and three nights. They demanded battle of kingship of the Fir Bolg. A battle was fought between them, to wit the first battle of Mag Tuired, in which a hundred thousand of the Fir Bolg fell. Thereafter they [the Tuatha De Dannan ] took the kingship of Ireland. Those are the Tuatha Dea - gods were their men of arts, non-gods their husbandmen. They knew the incantations of druids, and charioteers, and trappers, and cupbearers.

(55-56, translated by Macalister)

The Coming of the Milesians & the History of Gaelic Ireland

The sixth and final wave of settlers are the Milesians, who are identified as the descendants of the mythical Goídel Glas and Scota who sailed from Hispania. The Milesians quickly come into conflict with the Tuath Dé Danann, but they eventually agree to divide the land between them; The Milesians, ancestors of the Gaels, are given dominion above ground and the Tuath Dé Danann are allowed to dwell below Ireland.

The rest of the Lebor Gabála Érenn gives a fictionalized account of Irish history up to the Medieval period, and chronicles the pagan and early Christian kings of Ireland. Importantly, the Lebor Gabála Érenn weaves complex genealogies in which nearly every Irish ruler is descended from the Milesian kings. The passages of the Lebor Gabála Érenn which pertain to the more recent Christian kings of Ireland bears the closest resemblance to history, but even these contain many fictitious elements.

Modern Reception & Interpretations

Despite its fantastic elements, the Lebor Gabála Érenn provide historians with insight into Medieval Irish historical traditions. It has also been postulated that it may contain parallels to real events. For example, historians have drawn comparisons between the mythological settlement of Ireland by the Milesians, and the actual relationship of Celtic groups in Ireland and the Iberian Peninsula in prehistory. The possibility of pre-historic maritime links between Ireland and Iberia is still a matter of some debate however, and the tradition preserved in the Lebor Gabála Érenn is certainly far from reality. Although historians once treated the Lebor Gabála Érenn as an essential source on Irish history, recent archaeological discoveries and historical analysis in the 20th Century has led to the rejection of the Lebor Gabála Érenn as anything more than a Medieval fabrication.