Legalism in ancient China was a philosophical belief that human beings are more inclined to do wrong than right because they are motivated entirely by self-interest and require strict laws to control their impulses. It was developed by the philosopher Han Feizi (l. c. 280 - 233 BCE) of the state of Qin.

Han Feizi is thought to have been a student of the Confucian reformer (and last of the Five Great Sages of Confucianism), Xunzi (l. c. 310-c.235 BCE) who departed from the central precept of Confucianism that humans were basically good, claiming they most certainly were not for, if they were, they would not need instruction in goodness.

Han Feizi drew on this one aspect of Xunzi's work as well as earlier writings of the Warring States Period of China (c. 481 - 221 BCE) by a Qin statesman named Shang Yang (d. 338 BCE) to develop his philosophy that, since humans were inherently evil, laws to control and punish were a necessity for social order. Even though Legalism during the Qin Dynasty resulted in huge loss of life and culture, it should be remembered that the philosophy developed during a time of constant warfare in China when each state fought every other for control and imposing order on this chaos was, obviously, considered of the utmost importance.

The Adoption of Legalism

For over 200 years the people of China experienced war as their daily reality and a legalistic approach to trying to control people's worst impulses - controlling people through the threat of severe punishment for doing wrong - would have seemed like the best way to deal with the chaos. Shang Yang's legalism dealt with everyday situations but extended to how one should conduct one's self in war and he is credited with the tactics of total war which allowed the state of Qin to defeat the other warring states to control China.

Legalism became the official philosophy of the Qin Dynasty (221 - 206 BCE) when the first emperor of China, Shi Huangdi (r. 221-210 BCE), rose to power and banned all other philosophies as a corrupting influence. Confucianism was especially condemned because of its insistence on the basic goodness of human beings and its teaching that people only needed to be gently directed toward good in order to behave well.

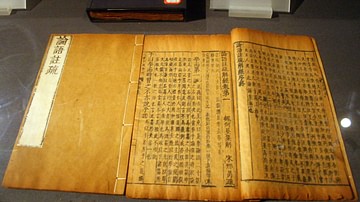

During the Qin Dynasty any books which did not support the Legalist philosophy were burned and writers, philosophers, and teachers of other philosophies were executed. The excesses of the Qin Dynasty's legalism made the regime very unpopular with the people of the time. After the Qin were overthrown, Legalism was abandoned in favor of Confucianism and this influenced the development of the culture of China significantly.

Beliefs & Practices

Legalism holds that human beings are essentially bad because they are inherently selfish. No one, unless forced to, willingly sacrifices for another. According to the precepts of Legalism, if it is in one's best interest to kill another person, that person will most probably be killed. In order to prevent such deaths, a ruler had to create a body of laws which would direct people's natural inclination of self-interest toward the good of the state.

Morality was of no concern to the legalist philosophers because they felt it played no part in people's decision-making process. In Legalism, laws direct one's natural inclinations for the betterment of all. The person who wants to kill their neighbor is prevented by law but would be allowed to kill others by joining the army. In this way the person's selfish desires are gratified and the state benefits by having a dedicated soldier.

Legalism was practiced through enacting laws to control the population of China. These laws would include how one was to address social superiors, women, children, servants as well as criminal law dealing with theft or murder. Since it was a given that people would act on their self-interest, and always in the worst way, the penalties for breaking the law were severe and included heavy fines, conscription in the army, or being sentenced to years of community service building public monuments or fortifications.

Other philosophies which argue for people's inherent goodness were considered dangerous lies which would lead people astray. The beliefs of philosophers like Confucius (l. 551-479 BCE), Mencius (l. 372-289 BCE), Mo-Ti (l. 470-391 BCE), or Lao-Tzu (l. c. 500 BCE), with their emphasis on finding the good within and expressing it, were considered threatening to a belief system which claimed the opposite. The scholar John M. Koller, writing on Legalism, states:

The basic presupposition of [Legalism] is that people are naturally inclined to wrongdoing, and therefore the authority of laws and the state are required for human welfare. This school is opposed to Confucianism in that, especially after Mengzi, Confucianism emphasized the inherent goodness of human nature. (208)

Legalism was not only opposed to Confucianism but could not tolerate it. Once Legalism was adopted by the Qin Dynasty, Confucianism faced the very real threat of extinction. This applied as well to the work of Xunzi, the Confucian reformer, as to any other Confucian work even though Xunzi was thought to have inspired Han Feizi in founding Legalism. In reality, the claim that human beings are essentially selfish and only act out of self-interest was only one aspect of Xunzi's philosophy. He argued that people could become better than they are, not simply through laws, but by self-discipline, education, and observance of ritual.

Legalism in the Qin Dynasty

Xunzi's larger vision for Confucian reforms were ignored by Han Feizi in the interests of expedience and praticality. When the Zhou Dynasty (1046 - 256 BCE) began to collapse, and the separate states of China under its rule fought each other for control, states sought the most expedient system to maintain social order. The seven states of China - Chu, Han, Qi, Qin, Wei, Yan, and Zhao - all believed they were fit to rule and replace the Zhou.

These states battled with each other again and again but none of them could gain an advantage over the others until King Ying Zheng of Qin adopted Han Feizi's philosophy of Legalism and Shang Yang's concept of total war, conducting domestic policy and military campaigns along both these lines to achieve victory. The old rules of chivalry which Chinese armies had always considered were ignored by the Qin as they crushed one state after another. When the last of the free states had been conquered, Ying Zheng declared himself the first emperor of China: Shi Huangdi.

The emperor and his chief advisor/prime minister Li Siu (also given as Li Si, l. c. 280-208 BCE, another student of Xunxi) understood how well Legalism had worked for the Qin in war and so adopted it as the official state philosophy in peace. According to historian and scholar Joshua J. Mark, Shi Huangdi "ordered the destruction of any history or philosophy books which did not correspond to Legalism, his family line, the state of Qin, or himself" and had over 400 Confucian scholars executed.

Under Shi Huangdi's reign those who broke the law, even through minor offenses, were sentenced to hard labor building the Great Wall or the Grand Canal or the new roads the Qin Dynasty required for moving troops and supplies. The Chinese people hated the Legalism of the Qin but were powerless against the Qin soldiers and governors who enforced the law.

The Han Dynasty & Suppression of Legalism

Legalism remained in effect throughout the Qin Dynasty until its fall in 206 BCE. After the Qin had fallen, the states of Chu and Han fought for control of the country until Xiang-Yu of Chu (l. 232-202 BCE) was defeated by Liu Bang of Han (l. c. 256-195 BCE) at the Battle of Gaixia in 202 BCE and the Han Dynasty was founded. The Han Dynasty reigned for a long time, from 202 BCE to 220 CE, and began many of the most important cultural advances in Chinese history, the opening of the Silk Road being only one of them.

They originally kept a form of Legalism as their official philosophy but it was a much gentler version than that of the Qin. The Emperor Wu (141-87 BCE) finally abandoned Legalism in favor of Confucianism and also made it illegal for anyone who followed the philosophies of Han Feizi or Shang Yang to hold public office.

Confucianism could be expressed openly again during the Han Dynasty. The suppression of Legalism and Legalist philosophers diminished the threat of the philosophy taking hold again and allowed for opposing views to be explored. This did not mean that Legalism disappeared or that it no longer had any effect on the Chinese culture, however. Legalism remained a go-to philosophy throughout China's history up into modern times. Whenever a government has felt it might be losing control it has resorted to some degree of Legalism.

The days of the supremacy of Legalism in China were over, though. Koller writes, "the long-term effect of the Legalist emphasis on laws and punishment was to strengthen Confucianism by making legal institutions a vehicle for Confucian morality" (208). The vacuum left by the rejection of Legalism was filled by Confucianism which provided the Chinese culture with a much more comfortable and all-embracing vision of humanity and how people could live together peacefully.