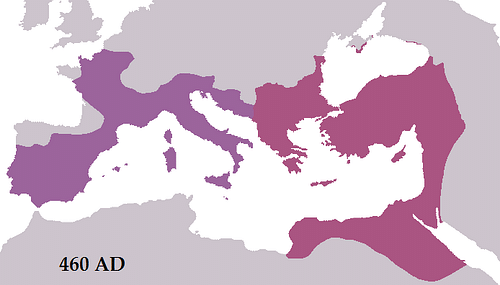

Leo I was emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 457 to 474 CE. He was also known as “Leo the Butcher” (Makelles) for the assassination of his patron and rival Aspar. Although his reign was lacklustre and included a serious defeat to the Vandals, he founded the Leonid dynasty, which ruled from Constantinople until 518 CE.

Succession

Leo acquired the throne not by inheritance but because he was selected by the gifted general who pulled the strings of Byzantine politics at that time, Aspar the Alan. The general had already been manipulating Leo's predecessor, Marcian (r. 450-457 CE), whom he had similarly promoted to emperor. Aspar, although the most powerful man at court, could not himself become emperor because of his barbarian background and unorthodox religious views. Consequently, the general did the next best thing and acquired himself not one but two successive puppet emperors.

Leo, formerly a soldier and then steward of Aspar's household, became emperor aged 56 on 7 February 457 CE and was the first Byzantine emperor to be crowned by the Patriarch (bishop) of Constantinople, in this case, Anatolios. Previously the legions lifting the emperor on their shields in the Hippodrome of Constantinople had sufficed, but from now on there would also be a bit of pomp and ceremony from the Church, too. It was a significant development which moved Byzantium one step further away from its Roman heritage and reinforced the role of the emperor as a Christian monarch; it would also influence most subsequent coronations in Western Europe right up to that of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 CE.

Leo & the Isaurians

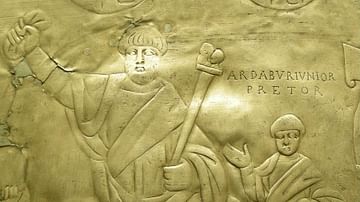

Aspar, as it turned out, had made a very poor choice in his puppet. Leo might have been getting on a bit, and he had no male heir to complicate matters of succession, but the emperor proved a lot more ambitious than his patron had hoped for. Leo was fully aware of Aspar's stranglehold on power and so he sought to undermine the general's strength at source: the army, and especially the Germans who dominated at least half of it. The emperor promoted as many Isaurians as he could to counterbalance the German faction and to try and win the army's loyalty to his own side. These wild tribesmen from Isauria in central and southern Asia Minor enjoyed a fearsome reputation as warriors, and in 466 CE, Leo even went so far as to give his daughter Ariadne as a wife for their chief Tarasicodissa, who would take the more Byzantine-friendly reign name of Zeno. Even better, Zeno was soon able to show that Aspar's son was guilty of treason and remove a little sparkle from the general's hitherto glittering reputation.

Aspar, however, did not sit idle while his power base was eroded from beneath him and he enlisted the help of the influential court figure Basiliscus, brother of Leo's wife Verina. The historian J. J. Norwich gives the following description of these unlikely bedfellows:

The two could scarcely have been more different. Aspar was without culture; as a convinced Arian, he came near to denying the godhead of Christ; as a leader of men he was the finest general of his time. Basiliscus was a Hellenized, well-educated Roman; a fanatical monophysite, for whom Christ was divine rather than human; and a man totally unfitted for any sort of command. They were flung together, however, by their common hatred of the Isaurians. (51)

The Vandals Disaster

There erupted a power struggle but not before Leo sent Basiliscus on a campaign against the Vandal king Genseric in 468 CE. The Vandals had still gone unpunished for their sacking of Rome in 455 CE, and Genseric was intent on persecuting orthodox Christians - two good reasons for Leo to gain some prestige in attacking the barbarians in North Africa. The state coffers were emptied and tons of gold invested in both the army and navy. Unfortunately for the Byzantines, Basiliscus proved inept and, despite a huge armada and an army of 100,000 men, he still managed to fail in his mission. Tricked by the Vandal king into delaying his attack, Basiliscus' fleet was caught napping and destroyed by enemy fireships off the coast of Mercurion. The commander fled back to a hot reception in Constantinople where he was forced to seek sanctuary in the Church of Hagia Sophia while a baying mob screamed for his head. Only his sister's pleas saved Basiliscus from execution for incompetence. Instead, Leo exiled the commander to Thrace, but he would return to trouble Byzantine politics sooner rather than later.

The army's defeat to the Vandals did not do Aspar any good either, as he was considered by many to be its commander-in-chief. Largely thanks to Isaurian support, the wrestle for power finally ended in Leo's favour with the deaths of Aspar and his son Ardabourios in 471 CE. Leo was considered the assassin of the pair who had been lured to the palace and dealt with by the court eunuchs. Thereafter, Leo was given the unflattering epithet of “the Butcher” (Makelles) by his opponents. Still, in comparison to many of his predecessors (and his successors), Leo's reign was a relatively calm one, free from the constant intrigue and literal backstabbing that seemed to plague the Byzantine court.

Death & Successors

When Leo died of dysentery on 3 February 474 CE, Zeno took the Byzantine throne, sharing it for form's sake with his young son Leo II. However, the very next year, and following the death of Leo II, Zeno was overthrown by his mother-in-law Verina and her brother Basiliscus. Zeno, however, regained his throne with help from Daniel the Stylite, the Pillar Saint, and would rule until 491 CE.