The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806) was a US military expedition of exploration, led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, whose goal was to explore the newly acquired western lands that comprised the Louisiana Purchase and to reach the Pacific Ocean. The journey, which covered about 8,000 miles (13,000 km), was a major step toward the westward expansion of the United States.

Lewis, Clark, and their men – known as the Corps of Discovery – embarked on their journey on 14 May 1804. They moved up the Missouri River, crossed over the Rocky Mountains, and paddled down the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean. After spending the winter of 1805-06 in present-day Oregon, the expedition began its return journey, arriving back in St. Louis on 23 September 1806, two years and four months after having first set out. The expedition succeeded in exploring the newly acquired western lands and giving the United States a better claim to the Oregon Country. They made around 140 detailed maps, marking out significant mountain ranges, rivers, and plains. The expedition also identified 178 types of plants and 122 animal species and subspecies that had previously been unknown to Euro-Americans.

Additionally, the Corps of Discovery encountered over two dozen Native American nations, some of whom had never encountered White people before. Most of the nations proved hospitable, some of them providing invaluable aid without which the expedition likely never would have succeeded. Sacagawea, a teenage Shoshone woman who had joined the expedition with her husband, acted as an interpreter between the explorers and native peoples they encountered, with her presence helping to assure the Native Americans that the expedition was not a threat. Lewis and Clark learned much about the languages and customs of the Native Americans they met, bringing many artifacts back with them.

Origins & Preparation

President Thomas Jefferson had long been fascinated with the American West. Though he would never travel further west than the Blue Ridge Mountains himself, he had always visualized this region as a land of vast untamed wilderness, where liberty and republicanism could thrive in spite of the corruption in the urbanizing East. Like many Americans before and after him, Jefferson believed the United States was destined to expand westward, to forge a so-called 'empire of liberty' that would one day encompass the entirety of the continent. As the American Revolutionary War was won in 1783, Jefferson was already trying to persuade famed war hero George Rogers Clark to lead a privately funded expedition into the West. Though Clark declined, Jefferson never gave up on his dream of a westward expedition.

After his election to the presidency in 1801, Jefferson finally had the opportunity to realize this ambition. By 1802, he had begun to plan the venture and appointed his private secretary, Meriwether Lewis, to lead it. Lewis was a 28-year-old Virginian, who had served in the militia during the suppression of the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion. He was just as enthusiastic as Jefferson about the West, and although Lewis lacked much formal education, Jefferson was confident in his abilities, writing that "Capt. Lewis is brave, prudent, habituated to the woods & familiar with Indian manners & customs" (Wood, 377). To better prepare the young man for leadership, Jefferson sent Lewis off to Philadelphia to study astronomy, medicine, cartography, ethnology, botany, lunar navigation, and other relevant subjects under the tutelage of some of the most renowned scientific experts in the country. While in Pennsylvania, Lewis purchased a Newfoundland dog named Seaman, who would remain his constant companion for the expedition.

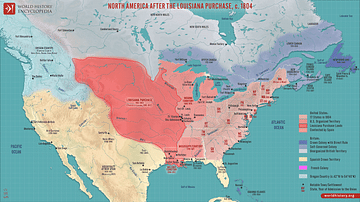

Initially, Jefferson presented the expedition as a merely scientific endeavor, to avoid arousing the suspicions of France, Spain, and Britain, who controlled the western lands that the president hoped to explore. This would change after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, when France sold the entirety of the Louisiana Territory – some 828,000 square miles (2,145,000 km²) – to the United States. Now, Jefferson could be more open about his exploratory intentions, instructing Lewis to detail and map out as much of the newly acquired western lands as possible, and establish a viable route of travel across the continent. Still, the president hoped the expedition could continue across the Louisiana Territory to the Pacific Northwest, thereby establishing an American presence in the region before the European nations could settle it in earnest. Jefferson also hoped that they could find the fabled Northwest Passage, that was supposed to cut across the continent and link to the Pacific. The expedition still had scientific and anthropological purposes, of course, but the goal of laying claim to the entire northwest came first and foremost.

In the months leading up to the expedition, Lewis decided that he needed a co-commander, someone more experienced with military leadership. In July 1803, he invited William Clark, a 33-year-old army veteran and the younger brother of George Rogers Clark, to share the command. The US secretary of war denied Lewis' request to elevate Clark to the rank of captain and instead commissioned him as a lieutenant, since the concept of joint leadership violated the army's ideas of chain of command. Lewis nevertheless treated Clark as his equal during the expedition, and always referred to him as 'captain' to keep his lower rank a secret from the men. This proved to be a prudent decision. As historian Gordon Wood describes their joint command:

Lewis and Clark seem never to have quarreled and only rarely disagreed with one another. They complimented each other beautifully. Clark had been a company commander and had explored the Mississippi. He knew how to handle enlisted men and was a better surveyor, map-maker, and waterman than Lewis. Where Lewis was apt to be moody and sometimes wander off alone, Clark was always tough, steady, and reliable. Best of all, the two captains were writers: they wrote continually, describing in often vivid and sharp prose much of what they encountered – plants, animals, people, weather, geography, and unusual experiences.

(378)

So, with Clark onboard, Lewis went to the federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, to procure weapons while Clark went to Kentucky to enlist men for the expedition, which was now referred to as the Corps of Discovery. By December, the Corps consisted of 45 men, including officers, enlisted men, civilian volunteers, and York, an enslaved African American man owned by Clark. The Corps established Camp Dubois at the mouth of the Missouri River, 18 miles (29 km) away from St. Louis, where they spent the winter gathering supplies and training.

The Expedition Begins: May 1804 to February 1805

On 14 May 1804, Clark and 30 members of the Corps of Discovery set out from Camp Dubois, travelling up the Missouri River in two pirogues and a 55-foot (17 m), single-masted keelboat designed by Lewis himself. They linked up with Lewis and the other men near St. Charles, Missouri, before continuing upriver. They made good time, covering 10-20 miles (16-32 km) a day by poling and paddling against the current. By July, they had made it to the mouth of the Platte River near present-day Omaha, Nebraska, where they set up camp at a place called Council Bluff. It was here, on 3 August, that the Corps had its first experience with Native Americans when they were visited by a small group of Oto and Missouri Indians. Lewis greeted them with gifts, telling them that they were now on US territory and that their new father, "the great Chief the President" was now "the only friend to whom you can look for protection, or from whom you can ask favors…he will take care to serve you, and not deceive you" (Wood, 379).

Three weeks later, the Corps reached present-day Sioux City, Iowa, where 22-year-old Sgt. Charles Floyd fell ill and died of appendicitis. Floyd was buried by the bluff that now bears his name; he would be the only member of the Corps to die during the entire expedition. At the end of August, the Corps entered the Great Plains, where they encountered immense herds of bison that numbered in the thousands, as well as animal species hitherto unknown to Europeans, including prairie dogs, grizzly bears, and pronghorn antelope. Near present-day South Dakota, the Corps was confronted by hostile bands of Lakota Sioux, who were suspicious of their intentions and refused to let them pass. This almost resulted in violence, but the situation was de-escalated by Lewis, who distributed tobacco to the Sioux warriors and thereby convinced them to let the expedition pass.

On 26 October 1804, the expedition reached the five villages of the Mandan Indians near present-day Bismarck, North Dakota, about 1,600 miles (2,575 km) from Camp Dubois. Lewis and Clark decided to winter here and constructed the palisaded Fort Mandan slightly downriver from the native villages. For the next five months, the Corps remained here, trading and establishing relations with the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians. During this time, the expedition was joined by a French-Canadian trapper, Toussaint Charbonneau, who agreed to act as an interpreter. Also joining the expedition was Charbonneau's teenaged Shoshone wife, Sacagawea. Sacagawea had been kidnapped from her village by the Hidatsa and sold off to Charbonneau, who had subsequently married her. When she met Lewis and Clark, she was heavily pregnant, and, in February 1805, she gave birth to a boy named Jean Baptiste. Lewis and Clark believed that the presence of Sacagawea and her baby could help convince any Native Americans they met that the expedition came in peace.

Over Rivers & Mountains: April to September 1805

On 7 April 1805, the Corps of Discovery broke camp. A small group was sent back to St. Louis in the keelboat with letters, maps, and boxes of materials to present to Jefferson, including live magpies and a prairie dog. The rest of the expedition continued westward, moving up the Missouri in the two pirogues and six dugout canoes. Lewis described the sight in his journal:

This little fleet, altho' not quite so respectable as those of Columbus or Capt. Cook, were still viewed by us with as much pleasure as those deservedly famed adventurers ever beheld theirs; and I dare say with quite as much anxiety for their safety and preservation.

(quoted in Wood, 379)

The captains were aided by geographical knowledge given to them by the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians, easing their way through present-day North Dakota and Montana. On 2 June, the expedition arrived at a fork in the river; after sending reconnaissance parties up both forks, the captains opted for the southern fork. Several days later, they came upon the Great Falls of the Missouri River, a series of waterfalls that Lewis described as "the grandest sight I ever beheld". The Corps had to portage 18 miles (29 km) around the falls, which consumed three weeks because of the treacherous terrain, frequent hailstorms, and an abundance of grizzly bears. They finished their portage on 4 July and celebrated Independence Day by drinking the last of their alcohol.

At the end of July, the expedition reached the Three Forks of the Missouri, where Sacagawea recognized the Beaverhead Rock from her childhood. She informed the captains that they were near the home of her people, the Shoshones. Eager to find the Shoshones to trade for horses, Lewis scouted ahead with three men. On 12 August, he climbed to the peak of Lemhi Pass at the Continental Divide, expecting to see plains intersected by a river flowing westward. Instead, he was greeted by the sight of a seemingly endless stretch of mountains, the Rockies. Although Lewis was initially disheartened, the expedition's luck turned around in mid-August, when they encountered a Shoshone band led by Sacagawea's brother, Chief Cameahwait. Cameahwait welcomed the expedition, who set up camp near the Shoshone village and named it Camp Fortunate.

The Shoshones gave the expedition the horses they needed and provided them with a guide named Old Toby, who knew the mountains well and had traveled through them before. Following Old Toby's lead, the Corps traveled through the Lemhi Pass and entered the Bitterroots, a range of the Rocky Mountains. This proved to be the expedition's most harrowing experience. The trail was steep and treacherous, and temperatures often dropped below freezing. Supplies had begun to run low, forcing the men to drink snowmelt and eat their horses. "I have been wet and as cold in every part as I ever was in my life," wrote Clark, "indeed I was at one time fearful my feet would freeze in the thin moccasins which I wore" (Britannica). After eleven miserable days, the Corps finally emerged from the Bitterroots, onto the Weippe Prairie, home of the Nez Perce.

To the Pacific & Back: October 1805 to September 1806

The captains succeeded in establishing friendly relations with the Nez Perce and secured their aid in building five dugout canoes from pine trees. With the help of two Nez Perce guides, the expedition descended the Clearwater and Snake Rivers, reaching the Columbia River on 16 October. Although they experienced fierce rapids, their spirits remained high, as it was known that the Columbia flowed into the Pacific. Finally, on 7 November 1805, they spotted the Pacific Ocean, with a relieved Clark recording in his journal: "Ocian in view! O! The joy!...Ocian 4142 miles from the Mouth of Missouri R." (Wood, 380). Further progress was delayed by storms, and after a democratic vote – in which even Sacagawea and York had a say – the Corps decided to stop for the winter. They passed a miserably cold winter at Fort Clatsop near present-day Astoria, Oregon.

On 23 March 1806, Lewis and Clark gifted the fort to the chief of the Clatsop Indians and began their journey home. They spent a month amongst the Nez Perce people as they waited for the snow to thaw before going back through the Bitterroots on the Lolo Trail. When they emerged from the mountains in late June, the expedition split up: Lewis led one group north to explore the Marias River and learn whether it flowed to Canada, while Clark led the second group south along the Yellowstone River. On 26 July, Lewis' party encountered eight Blackfoot Indians. Lewis offered to camp with them, only for a conflict to occur the next morning when the natives were caught trying to steal horses and guns. After a brief confrontation, Lewis' men shot and killed two of the Blackfeet, the only instance of violence during the expedition. The explorers then rode nonstop for 24 hours to escape reprisal. Clark's group, meanwhile, continued on without incident. Clark carved his name and the date into a sandstone formation that he named Pompey's Pillar in honor of Sacagawea's son, who Clark had nicknamed 'Pomp'.

On 12 August, Lewis and Clark reunited at the mouth of the Yellowstone River. From here, they traveled back down the Missouri River, covering 70 miles (112 km) a day, and returned to the Mandan villages on 14 August. The expedition lingered here for two days while the captains did business with the Mandan and Hidatsa chiefs. When it was time to go, the Corps bid farewell to Charbonneau, Sacagawea, and little Jean Baptiste, who stayed behind. The Corps continued rapidly down the Missouri River before finally reaching St. Louis on 23 September 1806. After two years and four months, the Corps of Discovery had concluded its journey, ending what is often regarded as the most significant overland exploration in US history.

Aftermath & Legacy

The Lewis and Clark Expedition was certainly a major success. While it had not discovered the Northwest Passage, it had achieved its main purpose of exploring and mapping out the lands between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Ocean, and the presence of American explorers gave the United States a stronger claim to the Oregon Country. The expedition brought back about 140 detailed maps and many records and samples of natural resources and botanical specimens new to Euro-Americans; over the course of the expedition, Lewis and Clark identified 178 new plants and 122 animal species and subspecies. Additionally, their expedition paved the way for increased settlement of the Louisiana Territory and facilitated fur trade in the Pacific Northwest. Inspired by Lewis and Clark's success, several other westward expeditions were commissioned, such as Zebulon Pike's expeditions into modern Colorado and New Mexico.

For their accomplishments, Lewis and Clark were each given double pay and 1,600 acres of land. In 1807, Lewis was appointed governor of the Louisiana Territory. He was successful in publishing the first territorial laws and did his best to uphold treaties with Native Americans, but he was criticized for his handling of land claims and his infrequent correspondence with his superiors. Lewis had long suffered from depression, and during this time his alcohol abuse only worsened. On 11 October 1809, while traveling from St. Louis to Washington, D.C., Lewis died from gunshot wounds to the head and chest; scholars still debate whether he committed suicide or was murdered. Clark, meanwhile, was appointed federal Indian agent and later became governor of the Missouri Territory. When Sacagawea died of an illness in 1812, he became the legal guardian of Jean Baptiste. In 1814, the journals of Lewis and Clark were published by Nicholas Biddle in his History of the Expedition Under the Commands of Captains Lewis and Clark. Biddle's account omitted many of the expedition's scientific discoveries, however, meaning that Lewis and Clark did not receive credit for many of their discoveries in nature.