The play Libation Bearers was written by one of the greatest of all Greek tragedians Aeschylus (c. 525-455 BCE). Winning first prize at the Dionysia competition in 458 BCE, Libation Bearers was the second play in the trilogy The Oresteia; the remaining two tragedies were Agamemnon and Eumenides. As was common in many of the competitions, there was also a satyr play, the lost Proteus.

In the first play, Agamemnon, the Greek king of Argos and commander of the forces against King Priam's Troy, has returned home victorious after ten grueling years. In his absence, his wife Clytemnestra has taken a lover who happens to be Agamemnon's first cousin Aegisthus. Hoping to rule Argos together, the conspiring couple decides to kill the returning king and his mistress Cassandra, the daughter of the defeated King Priam. In Libation Bearers, Orestes, the son of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, returns to Argos after several years and avenges his father's murder by killing his mother and her lover. In the third and final play, Eumenides, Orestes is put on trial in Athens for his crimes.

Aeschylus

The father of two future playwrights, Euphorion and Euaion, Aeschylus came from an aristocratic Greek family of Eleusis, an area west of Athens. Profoundly religious and a strong proponent of Athenian democracy, he fought at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC and possibly at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE. As a result of his radical beliefs, his plays often contain strong political themes. He began producing plays in the 490s BCE, winning his first victory in 484 BCE. Of his over 90 plays, only six have survived; the authorship of a seventh Prometheus Bound is in question. His trilogy Oresteia won a first at Dionysia in 458 BCE. Eventually, he won a total of 13 first-place victories, second only to Sophocles. Considered the most popular and influential of all tragedians of his era and older than both of his contemporaries Sophocles and Euripides, he is often referred to as the “Father of Greek Tragedy.”

He is credited with taking tragedy in a new direction, revolutionizing it. Prior to Aeschylus, a play's dialogue was hampered with only one actor. With his introduction of a second actor (and possibly a third), plot construction was given more freedom. Afterwards, the intricacy of plays increased. Unlike other playwrights, Aeschylus may have also designed costumes, trained his choruses, and possibly even acted in some of his own plays.

The Myth

The stories of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey and his account of the Trojan War serve as a backdrop to Aeschylus's trilogy. Since all three of the plays would have been performed on the same day at the Dionysia, most in the audience would already be well aware of the circumstances behind Agamemnon's gruesome death when the second play begins. In the queen's mind, the murder of her husband was simply an act of revenge. Because of Agamemnon's arrogance, the goddess Artemis had stilled the winds crippling the king's attempt to sail to Troy. She demanded a sacrifice: the life of their eldest daughter Iphigenia. With her death, the king and his fleet left Argos, and ten years later he returned victorious, bringing with him a concubine. The queen, having held an intense hatred for his husband for ten years, seized the opportunity and killed him as he bathed. She delivers the bodies of the slain king and his concubine to the people of Argos. She has had her revenge, and she vows there will be no more bloodshed.

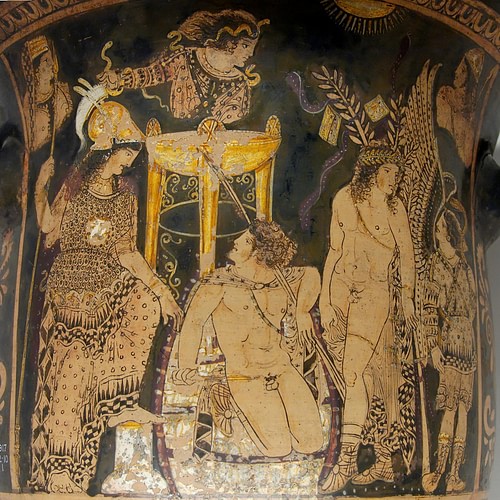

Libation Bearers begins with Orestes returning to Argos after an absence of several years; he had been banished in infancy. Orestes and his sister Electra accidentally meet at the tomb of Agamemnon. She had been sent there by Clytemnestra to make offerings or libations to the gods. Orestes tells his sister that he had been commanded by the oracle of Apollo to return to Argos and kill his mother and her lover. Posing as travelers, Orestes and his friend Plyades go to the palace to tell the queen of the death of her son. Clytemnestra sends an old nurse to summon Aegisthus to come to the palace unarmed. He arrives alone and is quickly overpowered and killed by Orestes. Although warned of the possible consequences, Orestes kills Clytemnestra. The Furies (spirits of vengeance) soon appear. Driven by madness, Orestes flees Argos.

Characters

Cast of characters for Libation Bearers:

- Orestes

- Plyades

- Electra

- Clytemnestra

- Aegisthus

- a nurse named Cilissa

- a slave

- and a chorus of captive slaves

Plot summary

The opening of the play takes place outside the Argive royal palace at the tomb of the slain king Agamemnon. Two young men stand in silence; Orestes, the king's only son, and his childhood friend, Plyades. Quietly, he leaves a lock of his hair to mark his grief. He speaks to his father:

He met his end in violence through a woman's treacherous trick. ... I was not by, my father, to mourn your death nor stretched my hand out when they took your corpse away. (Grene, 81)

He prays to Zeus to stand beside him and grant him vengeance for his father's death. As a group of women dressed in black approach, he and Plyades hide. Orestes recognizes one of them as being his younger sister, Electra but questions why she and the other women have come to mourn. They leave offerings - libations - to Agamemnon. Electra speaks aloud:

What shall I say as I pour out these outpourings of sorrow? Shall I say I bring it to the man beloved, from a loving wife, and mean my mother? I have not the daring to say this, nor know what else to say as I pour this liquid on my father's tomb. (84)

However, in her grief, she speaks of a day of destiny that “waits for the free man as well as for the man enslaved beneath an alien hand.” (84) The chorus leader tells her that her grief speaks for all of them and reminds her of her brother, Orestes who wanders far from Argos. He invites her to seek revenge. In response to his wishes, Electra appeals to the god Hermes - lord of the dead - to have pity on her and her brother. She speaks to him of her mother's lover Aegisthus who had helped kill her father. She prays that those who killed her father will, in turn, be killed. At the end of her prayer, she pleads for the return of his brother. Suddenly, she notices the strand of hair left by Orestes and realizes that the lock of hair is exactly like her own hair. She asks aloud if this were a gift from Orestes. She also notices footprints and believes them to be like her own. Somewhat confused she thinks she is going mad.

From their hiding place, Orestes and Plyades appear. Orestes speaks to his sister: "Pray for what is to come, and tell the gods they have brought your former prayers to pass. Pray for success” (89). Electra is reticent, for she does not know how to receive this stranger. Orestes reveals to her that the strands of hair are his, and he tells his sister how the oracle of Apollo instructed him to avenge his father's murder or, if he chooses not to comply or fails, he would suffer disaster.

The chorus, Electra, and Orestes sing to Agamemnon, asking for help in seeking revenge on Clytemnestra and Aegisthus. As they stand before his tomb, they realize that had he died in Troy he would be remembered and respected. His children would also be admired by all, and his tomb would be across the sea. They pray to Zeus to aid them to avenge his death and make his murderers accountable. Orestes appeals to his father in the underworld:

Send out your Right to battle on the side of those you love, or give us holds like those they caught you in. For they threw you. Would you not see them thrown in turn? (100)

He adds that since their father is dead, his children will be his voice. Then Orestes turns his attention to his sister and questions why she and the other women were pouring libations on their father's tomb. He was told by the chorus leader of his mother's strange and frightening dream. In the dream, she gave birth to a snake. The queen “wrapped it warm in clothing as if it was a child,” but the snake drew blood with the mother's milk (101). Clytemnestra woke from her sleep screaming “shaky with fear, as torches were kindled all about the house, out of the blind dark that had been on them” (102). She hoped that the libations poured on Agamemnon's tomb would be “medicinal for her disease.” Orestes believes he understands the meaning of the dream and interprets it for Electra and the others:

… it follows then, that as she nursed this hideous thing of prophecy, she must be cruelly murdered. I turn snake to kill her. This is what the dream speaks aloud. (102)

He establishes a plan: Electra is to return to the palace and say nothing of his return. Plyades and he will adopt a Parnassian dialect and a disguise. Once he gains access to the house he will kill Aegisthus. Soon, Orestes and Plyades arrive at the palace dressed as travelers. They are greeted at the door by one of the queen's servants. He says, “Announce me to the master of the house. It is to them I come, and I have new for them to hear.” (106) Clytemnestra comes to the door. The disguised Orestes, who identifies himself as a Daulian stranger, tells her how he met a foreigner, a Phocian named Stophius, who informed him of the death of a man named Orestes. The queen replies how his words have stripped her of all she had ever loved. She tells her servant to look after Orestes and Plyades. A nurse is immediately sent to summon Aegisthus.

Aegisthus arrives at the palace, he wants to question the travelers himself. Shortly afterwards, a servant runs from the palace. “Aegisthus lives no longer.” (114) Clytemnestra enters and speaks to the servant, “What is this, and why are you shouting in the house.” (114) She is told how the living are now being killed by the dead. The queen, realizing who the stranger really was, screams out how she had been won over with treachery. Orestes and Plyades enter with swords drawn. Orestes speaks directly to his mother:

You next: the other one in there has had enough. ... You shall lie in the same grave with him and never be unfaithful even in death. (115)

Orestes turns to his friend, asking what he should do, whether he should he be ashamed to kill his mother. Plyades reminds him of the oath he took at the oracle. Orestes tells Clytemnestra how he plans to kill her over her lover's body. She pleads for her life, reminding him how she had raised him as a child. Seeing that her plea was to no avail, she says that her curse will drag him down. “You are the snake I gave birth to, and gave the breast.” (117) She is led into the palace. Shortly, the chorus leader speaks; the queen is dead. As the doors of the palace open, Orestes stands over the bodies of Clytemnestra and Aegisthus:

Behold the twin tyrannies of our land, these two who killed my father and who sacked my house. (119)

But it is obvious that he is troubled. He has won a victory, but to him, the victory is polluted. Although he killed his mother, it was, in his mind, justified. Hoping to console the troubled Orestes, the chorus leader reminds him how he has liberated Argos. An obviously suffering Orestes replies:

Women who serve this house, they come like Gorgons, they wear robes of black, and they are wreathed in a tangle of snakes. I can no longer stay. (121)

He believes them to be the “bloodhounds of his mother's hate", which many interpret to mean the Furies. No one else can see them but him, and he must leave Argos.

Interpretation

Like his mother Clytemnestra in Agamemnon, Orestes seeks justice; justice for the murder of his father by his mother and Aegisthus. In the end, however, it is apparent that he questions whether or not justice was truly served. While he does not regret killing Aegisthus, the act of killing his mother sends him into despair. After the murder of the queen, Orestes is hounded by the Furies and flees Argos. According to David Grene's Aeschylus II, he returns to the oracle for purification for the murder of Clytemnestra. In Eumenides, the third play of the trilogy, he will put on trial for his actions.