The Library of Ashurbanipal (7th century BCE) is the oldest known systematically organized library in the world, established in Nineveh by the Neo-Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE) to preserve the history and culture of Mesopotamia. Over 30,000 texts were discovered at Nineveh in the mid-19th century, but the original collection is thought to have been much larger.

Contrary to often-repeated claims, the Library of Ashurbanipal was not the first library in the world. Libraries existed in Sumer, attached to scribal houses, temples, and palaces by the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE). Akkadians and Babylonians also had libraries and so did earlier Assyrian kings. Scribes in ancient Mesopotamia also kept private libraries aside from those they would have referenced at the palace, school, or temple. The Library of Ashurbanipal is just the oldest one systematically organized to preserve a comprehensive collection of knowledge (not limited to one subject or type of work) and, owing to the importance of the tablets found there, the most significant. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek writes:

[The Library of Ashurbanipal] was far from the first or only large collection of documents ever established in ancient Mesopotamia, but it does seem to have been an archive founded specifically for the sake of preserving the heritage of the past. The king's concern to conserve the literary riches of his cuneiform culture, that they might be read by scholars of the far future, is evidenced by the colophon associated with many of the tablets stored: 'For the Sake of Distant Days'. (250)

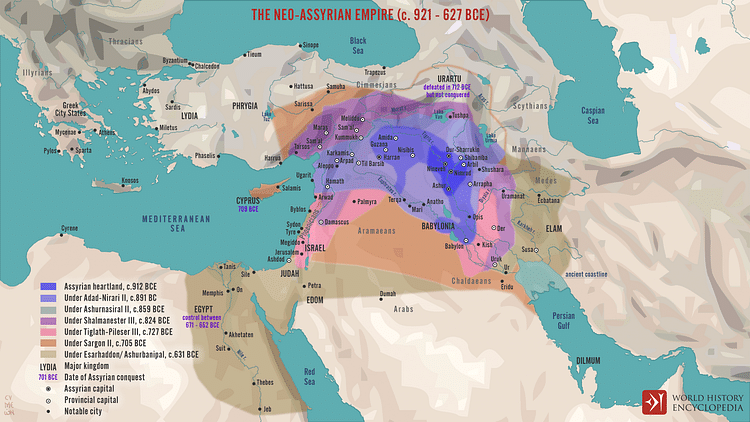

It is unclear when Ashurbanipal established the library but, according to Kriwaczek and other scholars, it was probably toward the end of his reign, sometime after the second Elam campaign of 647 BCE, although it is clear texts were being acquired earlier. If so, the library only stood for approximately 30 years. It was burned in the sack of Nineveh in 612 BCE by a coalition of Babylonians, Medes, and Persians as the Neo-Assyrian Empire fell.

The enemies of the Assyrians sought to wipe all memory of them from history, but, ironically, when the library fell, the ruined walls buried the clay cuneiform tablets that were the books, and the fires baked and preserved them. These tablets were discovered over 2,000 years later by archaeologists Sir Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam in a find that has been characterized by many scholars since as among the most important of the modern era.

Literacy & Rise to Power

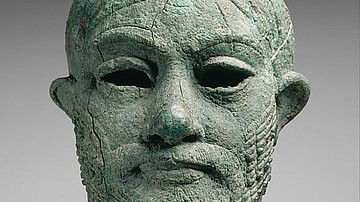

Ashurbanipal was the middle son of the Neo-Assyrian king Esarhaddon (r. 681-669 BCE) who had chosen his eldest son, Sin-iddina-apla, to succeed him. Ashurbanipal was sent to the edubba ("House of Tablets"), the scribal school, and received the standard education necessary to become a scribe. His younger brother, Shamash-shum-ukin, was most likely also educated as it is known that their sister, Serua-eterat (l. c. 652 BCE), was literate as evidenced by an extant letter in which she reprimands her sister-in-law (Ashurbanipal's wife) for laziness in her study habits.

Serua-eterat notes how her sister-in-law's carelessness regarding education could bring shame on the family, suggesting her siblings were also literate. It is also unlikely, no matter how progressive Esarhaddon may have been in educating his daughters, that he would have neglected the same for his sons, although it is unclear whether Sin-iddina-apla received the same level of education as Ashurbanipal or Serua-eterat.

Sin-iddina-apla died in 672 BCE, and Esarhaddon chose Ashurbanipal as his successor. In order to prevent the same problems he had to contend with when he came to power, having to fight his brothers for the throne of their father Sennacherib (r. 705-681 BCE), he forced his vassal states to swear their loyalty to Ashurbanipal in advance. Esarhaddon's mother, Zakutu (l. c. 728 to c. 668 BCE), a powerful woman at court, supported her son and grandson in issuing the Treaty of Zakutu, compelling all territories under Assyrian rule, as well as the members of the court, to accept Ashurbanipal as Esarhaddon's undisputed successor. When he came to the throne after Esarhaddon's death in 669 BCE, Ashurbanipal faced no resistance and could do as he pleased.

Reign & Military Campaigns

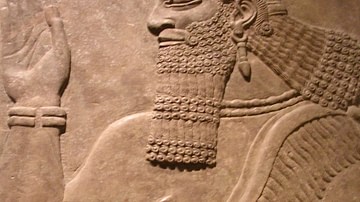

Esarhaddon had already designated Shamash-shum-ukin as the future king of Babylon, but Ashurbanipal, according to his own inscriptions, gave his younger brother even more responsibility and greater gifts than he was obliged to. After securing the southern regions of his empire, he finished what his father had begun and conquered Egypt c. 667-666 BCE. He then put down rebellions in Tyre, subdued Urartu, and reconquered Anatolia between 665-657 BCE.

Although Ashurbanipal clearly felt he treated his younger brother well, Shamash-shum-ukin secretly resented him and wanted to be king of the Assyrian Empire. In 653 BCE, he entered into negotiations with Elam promising his support if they would invade and overthrow his brother. When news reached Ashurbanipal that the Elamites were mobilizing their armies, he attacked, defeated them, and sacked their cities. He cut off the head of the Elamite king Teumann and the other nobles and brought them back to Nineveh where he hung them from trees in his garden as trophies.

He was unaware that his brother had instigated the Elamite aggression, but this became clear the following year when, in 652 BCE, Shamash-shum-ukin declared Babylonian independence and openly took Assyrian territories. Ashurbanipal marched on the city, placed it under siege for four years, and, when it fell, slaughtered the inhabitants. Shamash-shum-ukin set himself on fire to escape capture.

In 648/647 BCE, the Elamites were engaged in civil war, and Ashurbanipal seized the opportunity to attack while they were divided. He burned the cities to the ground, including Susa, slaughtered or deported large populations, and, according to his own inscriptions, sowed the land with salt after desecrating the tombs of their kings. Elam was turned into a wasteland, and Ashurbanipal returned to Nineveh triumphant and, most likely, secure in the knowledge that he had preserved his empire for his sons and their sons.

Assyrian Libraries & Divination

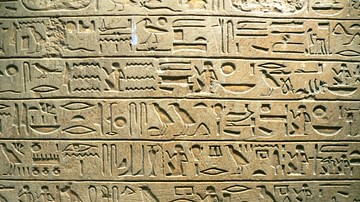

It seems it was at this time, c. 647/646 BCE, that he first conceived of a universal library that would house the collective knowledge of the past. Mesopotamian literature was first composed c. 2600 BCE in Sumer, and Sumerian texts were then preserved in Akkadian script after 2334 BCE with the Akkadians, Hittites, Babylonians, Kassites, and Assyrians continuing this tradition up to his time.

As a trained scribe, Ashurbanipal would have been aware of this, and perhaps having recently destroyed Babylon and Elam, considered that what had happened to them could also happen to him, his sons, and their sons. A library, containing all the knowledge of the past 2,000 years, would preserve his culture, however, as well as his own personal history. Further, establishing a resource that would include a comprehensive collection of divination texts could help him anticipate and answer any threats to his empire.

Assyrian libraries already existed at this time – as had Sumerian libraries, Akkadian libraries, and Babylonian libraries – but these held, largely, administrative and divination texts, copies of royal decrees and treaties, land and tax records, and trade agreements. Of the documents housed in royal Assyrian libraries, divination texts were the most important, as scholar Stephen Bertman explains:

Divination was based on the idea that association is tantamount to causality: that is, if two unusual events occur in proximity, one is responsible for the other. Thus, if a king died after an eclipse, the conclusion was reached that the eclipse foreshadowed his death. Likewise, if a shooting star was sighted the night before a military victory, a later sighting foretold yet another military success.

For most of Mesopotamian history, divination was used to guide the affairs of state. Few rulers would make or act upon an important decision without first consulting their royal fortunetellers. To predict the future, Mesopotamian seers studied celestial and meteorological phenomena and examined the organs and entrails of sacrificial animals ... In effect, the ancient seer was like the modern weatherman who uses his professional expertise to forecast what the future holds for us. (169)

The conclusions of these seers were written down in divination texts so they could be consulted by others. Ashurbanipal's father had a library of divination texts and so had his grandfather, Sennacherib, and his great-grandfather, Sargon II (r. 722-705 BCE), and so on into the past. Ashurbanipal decided to expand upon his own library, which would maintain the essential divination texts and the others but include works of every kind from everywhere in his empire, all of which, once safely tucked onto the shelves, would be preserved forever, surrounded by the secure walls of the great city of Nineveh.

The Library

Like his father before him, Ashurbanipal had an especially keen interest in divination and was eager to acquire any texts on the subject he did not already have. His correspondence with scribes and seers after c. 647 BCE shows an increasing concern for the future and his own personal health and well-being. He sent parties, which of course included scribes, throughout the empire to secure these and any other texts, which would then be copied and housed in his library. In a letter to the scribe Shadunu, Ashurbanipal (or a representative of the king) writes:

You shall search for and send to me ... rituals, prayers, stone inscriptions, and whatever is useful to royalty such as expiation texts for cities, to ward off the evil eye at a time of panic, and whatever else is required in the palace, all that is available, and also rare tablets of which no copies exist. I have written to the temple overseer and to the chief magistrate that you are to place the tablets in your storage house and that no one shall withhold any tablet from you. And in case you should see some tablet or ritual text which I have not mentioned, and which is suitable for the palace, examine it, take possession of it, and send it to me. (Kriwaczek, 251-252)

The acquisition of divination texts drove the entire enterprise. Ashurbanipal wanted everything that had ever been written but especially those works that could guide him in making the right choices concerning his future. Scholar Marc Van De Mieroop comments on the scribal process of the acquisitions:

The manuscripts were not merely collected but were copied out according to a standard format for the library. The cuneiform script and tablet layout were uniform, and at the end of each tablet an identification was provided stating that it belonged to Ashurbanipal's library. These subscripts or colophons could be simple stamps with the text "palace of Ashurbanipal, king of the universe, king of Assyria", but often indicated at length that the preceding texts were copied carefully from an original tablet, and that the copy was reviewed and checked. Indeed, the scribes were careful in their work. They indicated in their copies when they found a break in the original tablet and when they restored a lacuna. They corrected mistakes and, very rarely, indicated the variants they found in different original manuscripts.

The purpose of the library is indicated by the colophons, that is, a statement at the end that gives information on the nature and place of preservation of the tablet. The texts were kept in order to provide authorized versions that diviners and exorcists could use. Many of the manuscripts contained omens, and it was important that a correct version was on record. Also, literary and scholarly texts were kept, as specialists whose duty it was to protect the king and the state sometimes needed to quote them in their reports, and the accuracy of these quotes was important. (261-262)

The apprentice scribes would sign their work after it had been checked for accuracy by a superior. They would also sometimes add warnings against taking a tablet away from the library and not returning it. A fragment of the Babylonian poem The Poor Man of Nippur, found in the ruins of Ashurbanipal's library, concludes with such a warning in the lines, "Whoever takes away this tablet, may [the gods] take him away! May he have no descendants, no offspring…Do not take away the tablets! Do not disperse the library!"

Each tablet, once copied and checked, was placed on a shelf or in a nook along the walls of the library. Texts were not only copied onto clay tablets but also onto writing boards – panels of ivory or wood covered in wax into which cuneiform script could be inscribed. Many of these texts – both tablets and writing boards – were taken from Babylon after it fell to Ashurbanipal in 649/648 BCE. According to Van De Mieroop, a record of these texts indicates 2000 tablets and 300 writing boards "confiscated mostly from the private libraries of Babylonian priests or exorcists" acquired for the library in the year 648 BCE (261).

As the library's collection grew, it was the responsibility of the head librarian (keeper of the library) to maintain it and replace worn or broken tablets. The collection was housed in the building designated as the royal library as well as in the North Palace and included works on administrative matters, astronomy, astrology, botany, personal and royal correspondence, foreign correspondence, royal decrees, divination texts, religious texts and hymns, historical inscriptions, literature, and medical texts. Among the most famous works in the collection were the Myth of Adapa, the Myth of Etana, the Enuma Elish, and The Epic of Gilgamesh, all original stories concerning the creation of the world, the Fall of Man, and the Great Flood which, until the discovery of the library in the 19th century, were thought to be original to the Bible.

Destruction of the Library

Ashurbanipal was proud of his education and equally pleased with his library. In his inscriptions, he writes:

I, Ashurbanipal, within the palace, understood the wisdom of Nabu [the god of learning]. All the art of writing ... of every kind, I made myself the master of them all…I read the cunning tablets of Sumer, and the dark Akkadian language which is difficult rightly to use; I took my pleasure in reading stones inscribed before the [Great] flood ... The best of the scribal art, such works as none of the kings who went before me had ever learnt, remedies from the top of the head to the toenails, non-canonical selections, clever teachings, whatever pertains to the medical mastery of [the gods] Ninurta and Gula, I wrote on tablets, checked and collated, and deposited within my palace for perusing and reading.

(Kriwaczek, 250-251)

Unfortunately, although he is remembered as the most highly educated and literate of the Neo-Assyrian kings, Ashurbanipal is also noted as the most brutal. The Assyrian kings, especially those of the Neo-Assyrian Period (912-612 BCE), have the reputation for harsh policies in dealing with their enemies but, even among these, Ashurbanipal stands out as excessively cruel. His ruthless policies, however, would eventually contribute to the fall of the Assyrian Empire.

Although his inscriptions and reliefs make clear he was proud of his destruction of Elam, in doing so, he removed a buffer state between his empire and the land of the Medes and Persians who, with Elam gone, moved in and established communities. Ashurbanipal died of natural causes in 627 BCE, but, unlike his father, he had not provided equitably for his sons regarding succession. His son Ashur-etel-ilani succeeded him but soon after taking the throne was challenged by his twin brother, Sin-shar-ishkun, dividing the Assyrian Empire in civil war.

While the two brothers fought, the enemies of the Assyrians – including the Babylonians, Cimmerians, Medes, Persians, and Scythians – recognized their opportunity just as Ashurbanipal had years before in launching his campaign against Elam. A coalition led by the Medes and Babylonians descended upon the Assyrian cities in 612 BCE, sacking and destroying them. The great library at Nineveh fell as the city burned, and in time, its ruins were claimed by the earth, and it lay buried for the next 2000 years.

Conclusion

In the 19th century, archaeological expeditions were funded by Western institutions for the purpose of finding physical evidence to corroborate biblical narratives. At the time, the Bible was understood as a wholly original work and the oldest book in the world. No one knew the Sumerian civilization even existed and almost all that was known of the Babylonians and Assyrians came from the Bible. What the archaeologists found instead was the diverse civilizations of Mesopotamia whose history was unlocked when cuneiform script was deciphered.

Between c. 1850-1853, Layard and Rassam discovered the tablets of the Library of Ashurbanipal buried in the ruins of Nineveh (in modern Kouyunjik, Iraq), and by 1872, the scholar George Smith had translated The Epic of Gilgamesh and established that the biblical tale of the Great Flood was not an original account but a reworking of an ancient Sumerian and Babylonian myth.

As the texts of Ashurbanipal's library were translated further, knowledge of the past was considerably expanded, and for this reason, the discovery of the Library of Ashurbanipal is considered by some scholars the most significant of the 19th century and one of the most important of all time. Over 2,000 years after Ashurbanipal conceived of his library and his hope that his culture would be remembered "in distant days", his wish was granted and forever changed how people understood the history of the world.