![Lighthouse of Alexandria [Artist's Impression] (by Ubisoft Entertainment SA, Copyright, fair use) Lighthouse of Alexandria [Artist's Impression] (by Ubisoft Entertainment SA, Copyright, fair use)](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/7615.jpg?v=1722353049)

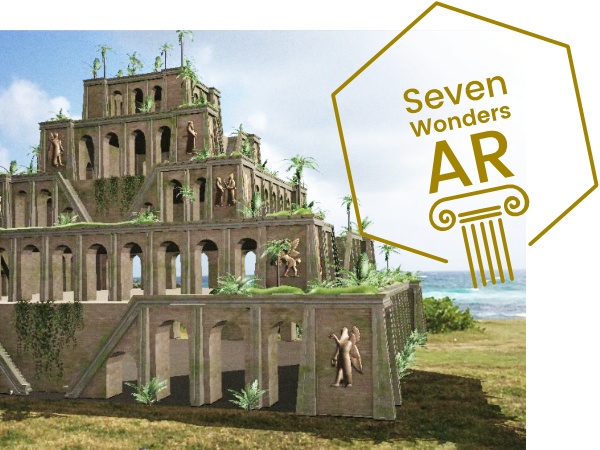

The Lighthouse of Alexandria was built on the island of Pharos outside the harbour of Alexandria, Egypt c. 300 - 280 BCE, during the reigns of Ptolemy I and II. With a height of over 100 metres (330 ft), the lighthouse was so impressive that it made it onto the established list of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Although now lost, the structure's lasting legacy, after standing for over 1600 years, is that it gave its Greek name 'Pharos' to the architectural genre of any tower with a light designed to guide mariners. Perhaps influencing later Arab minaret architecture and certainly creating a whole host of copycat structures in harbours around the Mediterranean, the lighthouse was, after the pyramids of Giza, the tallest structure in the world built by human hands.

Alexandria

Alexandria in Egypt was founded by Alexander the Great in 331 BCE, and thanks to its two natural harbours on the Nile Delta, the city prospered as a trading port under the Ptolemaic dynasty (305-30 BCE) and throughout antiquity. A cosmopolitan city with citizens from all over the Greek world, the city had its own assembly and coinage and became a renowned centre of learning.

Around 300 BCE Ptolemy I Soter (r. 323 - 282 BCE) commissioned the building of a massive lighthouse to guide ships into Alexandria and provide a permanent reminder of his power and greatness. The project was completed some 20 years later by his son and successor Ptolemy II (r. 285-246 BCE). The structure only added to the impressive list of things to see at the great city which included the tomb of Alexander, the Museum (an institution for scholars), the Serapeum temple, and the magnificent library.

The Lighthouse

According to several ancient sources, the lighthouse was the work of the architect Sostratus of Cnidus, but he may have been the project's financial backer. The structure was located on the very tip of the limestone islet of Pharos facing the harbours of Alexandria. These two natural harbours were the Great Harbour and the whimsically named Eunostos or 'Harbour of Fortunate Return'. The mainland was linked to the island of Pharos by a causeway, the Heptastadion, which measured around 1,2 km (0.75 miles). The lighthouse, we are informed by a contemporary writer named Poseidippos, was intended to guide and protect sailors and to that end was dedicated to two gods, Zeus Soter (Deliverer) - whose dedicatory inscription on the tower was made with half-metre high letters - and possibly Proteus, the Greek sea god, also known as the 'Old man of the Sea'.

The lighthouse at Alexandria was certainly not the first such aid to ancient mariners but it was probably the first monumental one. Thasos, the north Aegean island, for example, was known to have had a tower-lighthouse in the Archaic period, and beacons and landmarks were widely used by cities to help sailors across the Mediterranean. Ancient lighthouses were built primarily as navigational aids for where a harbour was located rather than as a warning of hazardous shallows or submerged rocks, although, because of the dangerous waters of Alexandria's harbour, the Pharos performed both functions.

Strabo (c. 64 BCE - c. 24 CE), the Greek geographer and traveller made the following observations on Pharos:

This extremity itself of the island is a rock, washed by the sea on all sides, with a tower upon it of the same name as the island, admirably constructed of white marble, with several stories. Sostratus of Cnidus, a friend of the kings, erected it for the safety of mariners, as the inscription imports. For as the coast on each side is low and without harbours, with reefs and shallows, an elevated and conspicuous mark was required to enable navigators coming in from the open sea to direct their course exactly to the entrance of the harbour. (Geography, 17.1)

The exact design of the lighthouse, unfortunately, is not made clear by ancient writers, with descriptions often being vague, confusing, and conflicting. Most sources do agree that the tower was white (making it more visible) and that it had three floors - the lowest being rectangular, the middle one octagonal, and the top one round. Also (mostly) agreed upon is the presence of a statue of Zeus Soter on the top. Later Arab writers describe a ramp rising around the outside of the lower part of the tower and an internal staircase to reach the upper levels. Modern historians have debated the height of the tower, and estimates range from 100 to 140 metres (330-460 ft), which would, in any case, have made the Pharos the second tallest architectural structure in the world after the pyramids at Giza.

A fire, likely burning oil as wood was scarce, was kept at the top of the tower to make it visible at night, but whether this was so from the outset is debated by historians, largely because the earliest references to the Pharos in the works of ancient writers make no mention at all of a light. Later sources do describe the Pharos as a lighthouse and not merely a landmark tower useful only during daylight. The flame and several other points regarding the lighthouse are mentioned in the following description by the 1st-century CE Roman writer Pliny the Elder:

The cost of its erection was eight hundred talents, they say; and, not to omit the magnanimity that was shown by King Ptolemæus on this occasion, he gave permission to the architect, Sostratus of Cnidos, to inscribe his name upon the edifice itself. The object of it is, by the light of its fires at night, to give warning to ships, of the neighbouring shoals, and to point out to them the entrance of the harbour. (Natural History, 36.18)

According to later Arab sources, there was even a mirror (presumably of polished bronze) to reflect the flame over a greater distance out to sea. The mirror may also have functioned as a reflector of the sun. The tower, with no light visible, appears on Roman imperial coinage of the city (from Domitian to Commodus, 81-192 CE), which clearly show a large, narrow-windowed tower topped with a monumental statue and two smaller figures of Triton blowing a conch shell. These coins show the entrance to the tower being at the very base while later Arab descriptions have it higher up. The Pharos also appeared in mosaics and sarcophagi throughout antiquity, confirming its wide fame.

The Seven Wonders

Some of the monuments of the ancient world so impressed visitors from far and wide with their beauty, artistic and architectural ambition, and sheer scale that their reputation grew as 'must-see' (themata) sights for the ancient traveller and pilgrim. Seven such monuments became the original 'bucket list' when ancient writers such as Herodotus, Callimachus of Cyrene, Antipater of Sidon, and Philo of Byzantium compiled shortlists of the most wonderful sights of the ancient world. The Lighthouse of Alexandria made it onto the established list of Seven Wonders, albeit rather later than the others, because it was such a tall and unique structure. The tower's design was copied to protect harbours and mariners throughout the ancient world, and it became so famous as a lighthouse that the term pharos has been applied ever since to any such tower intended to aid shipping, and it is still the word for a lighthouse in many modern languages.

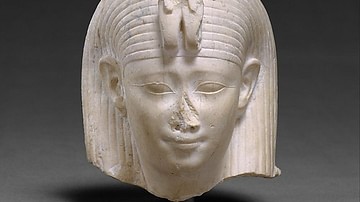

The lighthouse disappears from the historical record after the 14th century, presumably finally toppled by another earthquake sometime in the 1330s. The tower's granite foundations were reused in the Qait Bey Fort, built in the 15th century. Modern marine archaeology in the area - the sea level has risen since antiquity - has revealed several stone fragments and two monumental figures of Ptolemy I and his queen, Berenice, which may well have once belonged to the tower and its immediate vicinity.