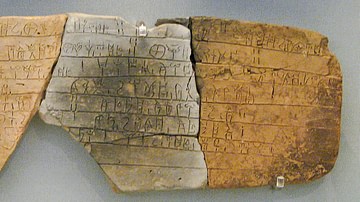

Linear A script was used by the Minoan civilization centred on Crete during the Bronze Age. Used from around 1850 to around 1450 BCE, the script has never been deciphered. Artefacts bearing Linear A script, most commonly clay tablets, have been found across the Mediterranean, evidence that Minoan trade was conducted with such islands as Rhodes, Thera, and the Cyclades.

Origins & Development

Linear A script is one of a group of written languages that linguists identify as related syllabic scripts used during the Bronze Age in the Aegean and the wider Mediterranean. The oldest identified script in Europe is the Cretan Hieroglyphic script, which was in use from around 2000 to 1650 BCE. This script, which uses pictures to denote objects and later representative sounds, remains undeciphered. Linear A, perhaps arriving a little later (the point is still under debate by historians), was prevalent from around 1850 to 1450 BCE and has also never been deciphered. At the early Minoan palaces, Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A script were used simultaneously for a period. There is a clear (but not absolute divide) in terms of artefacts bearing Cretan Hieroglyphic script and Linear A script, with the former appearing more in the north of Crete and the latter more in the south. Linear A script was being used across the whole of the island by the late 16th century BCE.

Linear A script is composed of at least 90 characters, which can be grouped into syllabic signs, ideograms, and symbols which denote numbers and fractions. In addition, monograms were made from the clustering of two or three symbols. The historian H. Thomas suggests that there are over 800 words identifiable in Linear A script. The famed Greek historian S. Alexiou gives the following description of the script:

This script is termed Linear because it is made up of signs which, although derived from ideograms, are no longer recognizable as representations of objects, but consists of lines grouped in abstract formations. (127)

The later Linear B script of the Mycenaean civilization was developed from Linear A (about 70% of Linear A symbols appear in Linear B) and was used to express the language we today call Mycenaean Greek (deciphered in 1952 CE). Linear A script, then, is an important indicator of a continuing though changing culture in the ancient Aegean.

Minoan Crete

The Minoans flourished in the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000 to c. 1450 BCE) on the island of Crete located in the eastern Mediterranean. Here they developed large settlements at sites like Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and Zakros. These sites all had labyrinth-like palace complexes, tombs, and cemeteries. The palace structures may have been political, trade, administrative, or religious centres, or performed a combination of these functions. The relationship between the different palaces and the power structure within them or over the island as a whole is not clear due to a lack of archaeological and literary evidence. It is clear, however, that the palaces exerted some kind of localised control, in particular, in the gathering and storage of surplus materials – wine, oil, grain, precious metals, and ceramics. Small towns, villages, and farms were spread around the territory seemingly controlled by a single palace. Roads connected these isolated settlements to each other and the main centre.

The first palaces were constructed around 2000 BCE and, following destructive earthquakes and fires, rebuilt again c. 1700 BCE. These second palaces survived until their final destruction between 1500 BCE and 1450 BCE, once again by either earthquake, fire, or possibly invasion (or a combination of all three).

There is a general agreement among historians that the Minoan palaces on Crete were independent of each other up to 1700 BCE, and thereafter they came under the sway of the largest site, Knossos. This domination is evidenced by a greater uniformity in architecture across the island and the wider use of Linear A script in various palace sites as attested by finds of rectangular clay tablets most likely used for administrative purposes and record-keeping. Artefacts bearing Linear A script have been found not only at the larger sites like Knossos, Phaistos, Zakros, and Chania but also in many smaller sites such as Tylissos and Hagia Triada, at single and more isolated 'villas' like Archanes, Sklavokampos, Myrtos Pyrgos, and Gournia, in remote cave and mountain sanctuaries such as Iouchtas, Kato Symi, and Mount Petsophas, and in tombs. Linear A script, therefore, has been taken by some historians as an important indicator that there was some sort of single centralised authority in Minoan Crete.

Possible Uses of Linear A Script

Although Linear A script has yet to be deciphered, scholars are generally agreed that its purpose was mainly for administration. Clay tablets bearing Linear A were used as records of trade transactions involving such goods as foodstuffs, livestock, pottery, and textiles. The tablets can also note personnel information. However, given that the script has yet to be deciphered, the interpretation of specific tablets remains tentative. As the historian V. La Rosa notes: "The exact nature of the registrations is uncertain; they might refer to inputs and outputs from the storerooms, to the distribution of goods in exchange for work, to transactions, and perhaps also to taxes" (Cline, 499).

Besides clay tablets, Linear A appears on disks made of clay, which were additionally impressed with one or more seals. These roundels, which often have an inscription on both sides, may have been used as receipts. Another type of disk, sometimes with a scalloped edge, has one or two central holes, perhaps to attach the disk to a papyrus scroll as a label. A third, related type is a rough clay stopper used to seal jars, sacks, or other containers. These devices carry a seal impression only and are not inscribed with Linear A script, but they are often found in proximity to objects which are. Rarer artefacts bearing the script include clay versions or attachments of now-lost records once made on perishable materials such as papyrus and parchment (the clay part prevented the papyrus or parchment from being opened by an unauthorised person undetected).

The possible connection between Linear A and administration is reinforced by their location, as at Zakros, for example, where there was a dedicated archive room of the inscribed tablets, and at Hagia Triada, where a single villa contained 147 tablets and 20 roundels. It is important to note, though, that Linear A script-bearing artefacts have been found in all contexts at Minoan sites, not only storerooms. Furthering the hypothesis of a primarily administrative function, however, is the fact that certain seal markings on tablets at one site very often match exactly those seals used at other sites. An additional connection with administration and trade is that Linear A signs were used to denote specific measuring weights, and they often appear on loom weights. Amongst the few sign groups which can be interpreted with some confidence is ku-ro, which is taken to mean "total", and po-to-ku-ro meaning "grand total", since these marks appear so frequently at the end of lists of numbers.

There are examples of other uses of Linear A given the context of finds at sanctuary sites. Stone offering tables, double-axes made using bronze, silver, and gold, and jewellery such as rings and pins have all been discovered with Linear A script marked on them. The religious context of these finds strongly suggests they were intended as votive offerings, and the script likely denotes proper nouns, perhaps of deities or the name of the person making the offering. Linear A script on such cult objects tends to be longer than those in the administrative documents, often the length of sentences. Another medium for the script was pottery, particularly the large storage jars known as pithoi. The symbols on these jars are typically three or four in number and could indicate the contents of the jars, the owner of the jar or its maker, or even a deity.

A third category of objects carrying Linear A script is in architecture. What could be mason's marks using the script have been incised into stone blocks. Plaster walls have also exhibited the script in cases of ancient graffiti. This graffiti and some of the scripts on pottery were made using ink such as that extracted from the octopus (itself a familiar subject of Minoan pottery decoration). As the Minoan historian E. Hallager notes: "…the fact that Linear A script was used on many noneconomic items and was also written in ink, seems to indicate that the script was much more extensively used during the LM 1 period [16-15th century BCE] than the preserved inscriptions might otherwise lead us to think" (Cline, 152).

The Spread of Linear A

As the Minoans traded across the Mediterranean, so they spread their ideas on religion, art, architecture, pottery, and language. For example, the prehistoric site of Trianda (Ialysos) on the northwest coast of Rhodes developed into a major trade centre during the Bronze Age. From the 16th century BCE, trade with the Minoan civilization on Crete is evidenced by finds of artefacts bearing Linear A script, as well as other elements of Cretan culture such as measuring weights, Minoan pottery, Minoan-like frescoes, and examples of Minoan architecture. Other islands which traded with the Minoans and which have provided archaeologists with further examples of Linear A script include Thera (modern Santorini), Kythira, Samothrace, the Cyclades group (e.g. Kea, Milos), Miletus (in modern western Turkey), and Tel Harror in Israel. Locally-made pottery and stone items found at the latter two sites, which have inscriptions of Linear A, suggest the use of the script there (perhaps by a resident Minoan immigrant) rather than the mere importation of inscribed goods from a distant Minoan settlement.

The Minoan Decline

The Minoan civilization went into decline and was ultimately replaced by the Mycenaean culture of mainland Greece in the mid-2nd millennium BCE. Minoan palaces and settlements on Crete show evidence of fire and destruction c. 1450 BCE, but not at Knossos (which was destroyed perhaps a century later). This destruction may have been the work of invading Mycenaeans, but alternative explanations include earthquakes, volcanic activity, stress of overpopulation on the environment, and a weakening of the established order in Minoan society as the competition for resources increased. Whatever the cause, most of the Minoan sites were abandoned by 1200 BCE. The Linear A script, as we have seen, partially returned in a modified form as the Mycenaean Linear B script from the late 15th century BCE.

The possibility of ever deciphering Linear A script depends on finding more examples of it, particularly, more lengthy texts or an equivalent of the Rosetta Stone, as here explained by the Encyclopedia of Ancient History:

Prospects for the decipherment of Linear A remain remote, because the surviving corpus is too small to yield results through pure structural analysis, and the language – or languages – underlying the script are probably unrelated to others known from the ancient world.

(4092)