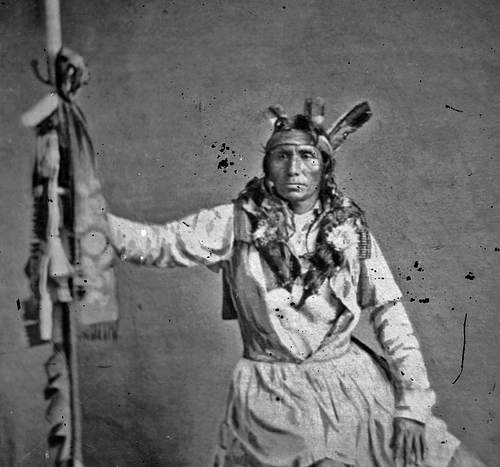

Little Crow (Taoyateduta, also known as Little Crow III, l. c. 1810-1863) was a Dakota Sioux chief best known as the leader of the Mdewakanton Dakota (Santee) Sioux during the Dakota War of 1862. After years of trying to maintain peaceful relations with the Euro-Americans, despite every broken treaty, Little Crow was left with no choice but to declare war.

The Dakota War (18 August to 26 September 1862) was a direct result of the failure of the US government to keep the promises made in the Treaty of Mendota in 1851, which promised the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute Sioux over $1 million for their lands; money the Sioux never saw. In 1858, Little Crow led a delegation to Washington, D.C., to address the problem, but this only resulted in the forced surrender of even more land. By 1862, because of his participation in these negotiations, Little Crow had fallen out of favor with his people.

Dakota War & Death

By this time, the US government had made more promises they had no intention of keeping regarding housing, stipends, educational and agricultural programs, and medical care in return for even more land. Many of the Dakota were starving to death and restricted to a land allotment of 20 miles (32 km) of poor soil. On 17 August 1862, four Dakota killed five settlers during an argument and appealed to their chiefs for protection. The chiefs then sought the support of Little Crow in declaring war. Even though he did not wish to fight, feeling it was futile, he agreed to die with them and launched the Dakota War the next morning.

He survived the conflict only to be killed on 3 July 1863 by the farmer Nathan Lamson and his son Chauncey, who did not even know who he was. Little Crow was picking raspberries with his son, Wowinape, when they were seen and fired upon. Wowinape fled after his father was killed, and Lamson reported the shooting to others, who mutilated Little Crow's body, dragging it through the main street of Hutchinson, Minnesota, and throwing it into the offal pit of the slaughterhouse.

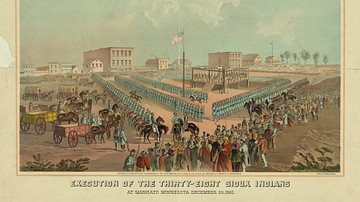

When Wowinape was captured on 28 July and told the authorities of Little Crow's death, only then did the people of Hutchinson realize whose body was in the pit. Lamson was then awarded $500.00 for his service in killing the Dakota leader, and Chauncey received $75.00 for Little Crow's scalp. The scalp was given to the Minnesota Historical Society in 1868, Little Crow's skull in 1896, and his assembled remains were put on display until 1971 when Wowinape's son, Jesse Wakeman, negotiated their return to the family, and these were then buried according to proper Dakota funerary rites.

Text

His biography was written by the Sioux author and physician Charles A. Eastman (also known as Ohiyesa, l. 1858-1939) in his Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains (1916) based on oral tradition and information gathered from Little Crow's family and friends. Some of the details of Eastman's account, especially of the assassination attempt staged by Little Crow's half-brothers, differ from those of other writers, but the overall accuracy of Eastman's work has been accepted.

The following text is from the 1939 edition of Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains, republished in 2016.

Chief Little Crow was the eldest son of Cetanwakuwa (Charging Hawk). It was on account of his father's name, mistranslated Crow, that he was called by the whites "Little Crow." His real name was Taoyateduta, "His Red People".

As far back as Minnesota history goes, a band of the Sioux called Kaposia (Light Weight, because they were said to travel light) inhabited the Mille Lacs region. Later they dwelt about St. Croix Falls, and still later near St. Paul. In 1840, Cetanwakuwa was still living in what is now West St. Paul, but he was soon after killed by the accidental discharge of his gun.

It was during a period of demoralization for the Kaposias that Little Crow became the leader of his people. His father, a well-known chief, had three wives, all from different bands of the Sioux. He was the only son of the first wife, a Leaf Dweller. There were two sons of the second and two of the third wife, and the second set of brothers conspired to kill their half-brother in order to keep the chieftainship in the family.

Two kegs of whisky were bought, and all the men of the tribe invited to a feast. It was planned to pick some sort of quarrel when all were drunk, and in the confusion Little Crow was to be murdered. The plot went smoothly until the last instant, when a young brave saved the intended victim by knocking the gun aside with his hatchet, so that the shot went wild. However, it broke his right arm, which remained crooked all his life. The friends of the young chieftain hastily withdrew, avoiding a general fight; and later the council of the Kaposias condemned the two brothers, both of whom were executed, leaving him in undisputed possession.

Such was the opening of a stormy career. Little Crow's mother had been a chief's daughter, celebrated for her beauty and spirit, and it is said that she used to plunge him into the lake through a hole in the ice, rubbing him afterward with snow, to strengthen his nerves, and that she would remain with him alone in the deep woods for days at a time, so that he might know that solitude is good, and not fear to be alone with nature.

"My son," she would say, "if you are to be a leader of men, you must listen in silence to the mystery, the spirit."

At a very early age she made a feast for her boy and announced that he would fast two days. This is what might be called a formal presentation to the spirit or God. She greatly desired him to become a worthy leader according to the ideas of her people. It appears that she left her husband when he took a second wife and lived with her own band till her death. She did not marry again.

Little Crow was an intensely ambitious man and without physical fear. He was always in perfect training and early acquired the art of warfare of the Indian type. It is told of him that when he was about ten years old, he engaged with other boys in a sham battle on the shore of a lake near St. Paul. Both sides were encamped at a little distance from one another, and the rule was that the enemy must be surprised, otherwise the attack would be considered a failure. One must come within so many paces undiscovered in order to be counted successful. Our hero had a favorite dog which, at his earnest request, was allowed to take part in the game, and as a scout he entered the enemy camp unseen, by the help of his dog.

When he was twelve, he saved the life of a companion who had broken through the ice by tying the end of a pack line to a log, then at great risk to himself carrying it to the edge of the hole where his comrade went down. It is said that he also broke in, but both boys saved themselves by means of the line.

As a young man, Little Crow was always ready to serve his people as a messenger to other tribes, a duty involving much danger and hardship. He was also known as one of the best hunters in his band. Although still young, he had already a war record when he became chief of the Kaposias, at a time when the Sioux were facing the greatest and most far-reaching changes that had ever come to them.

At this juncture in the history of the northwest and its native inhabitants, the various fur companies had paramount influence. They did not hesitate to impress the Indians with the idea that they were the authorized representatives of the white races or peoples, and they were quick to realize the desirability of controlling the natives through their most influential chiefs. Little Crow became quite popular with post traders and factors. He was an orator as well as a diplomat, and one of the first of his nation to indulge in politics and promote unstable schemes to the detriment of his people.

When the United States Government went into the business of acquiring territory from the Indians so that the flood of western settlement might not be checked, commissions were sent out to negotiate treaties, and in case of failure it often happened that a delegation of leading men of the tribe were invited to Washington. At that period, these visiting chiefs, attired in all the splendor of their costumes of ceremony, were treated like ambassadors from foreign countries.

One winter in the late eighteen-fifties, a major general of the army gave a dinner to the Indian chiefs then in the city, and on this occasion Little Crow was appointed toastmaster. There were present a number of Senators and members of Congress, as well as judges of the Supreme Court, cabinet officers, and other distinguished citizens. When all the guests were seated, the Sioux arose and addressed them with much dignity as follows:

"Warriors and friends: I am informed that the great white war chief who of his generosity and comradeship has given us this feast, has expressed the wish that we may follow to-night the usages and customs of my people. In other words, this is a warriors' feast, a braves' meal. I call upon the Ojibway chief, the Hole-in-the-Day, to give the lone wolf's hunger call, after which we will join him in our usual manner."

The tall and handsome Ojibway now rose and straightened his superb form to utter one of the clearest and longest wolf howls that was ever heard in Washington, and at its close came a tremendous burst of war whoops that fairly rent the air, and no doubt electrified the officials there present.

On one occasion Little Crow was invited by the commander of Fort Ridgeley, Minnesota, to call at the fort. On his way back, in company with a half-breed named Ross and the interpreter Mitchell, he was ambushed by a party of Ojibway, and again wounded in the same arm that had been broken in his attempted assassination. His companion Ross was killed, but he managed to hold the war party at bay until help came and thus saved his life.

More and more as time passed, this naturally brave and ambitious man became a prey to the selfish interests of the traders and politicians. The immediate causes of the Sioux outbreak of 1862 came in quick succession to inflame to desperate action an outraged people. The two bands on the so-called "lower reservations" in Minnesota were Indians for whom nature had provided most abundantly in their free existence. After one hundred and fifty years of friendly intercourse first with the French, then the English, and finally the Americans, they found themselves cut off from every natural resource, on a tract of land twenty miles by thirty, which to them was virtual imprisonment. By treaty stipulation with the government, they were to be fed and clothed, houses were to be built for them, the men taught agriculture, and schools provided for the children. In addition to this, a trust fund of a million and a half was to be set aside for them, at five per cent interest, the interest to be paid annually per capita. They had signed the treaty under pressure, believing in these promises on the faith of a great nation.

However, on entering the new life, the resources so rosily described to them failed to materialize. Many families faced starvation every winter, their only support the store of the Indian trader, who was baiting his trap for their destruction. Very gradually they awoke to the facts. At last, it was planned to secure from them the north half of their reservation for ninety-eight thousand dollars, but it was not explained to the Indians that the traders were to receive all the money. Little Crow made the greatest mistake of his life when he signed this agreement.

Meanwhile, to make matters worse, the cash annuities were not paid for nearly two years. Civil War had begun. When it was learned that the traders had taken all of the ninety-eight thousand dollars "on account", there was very bitter feeling. In fact, the heads of the leading stores were afraid to go about as usual, and most of them stayed in St. Paul. Little Crow was justly held in part responsible for the deceit, and his life was not safe.

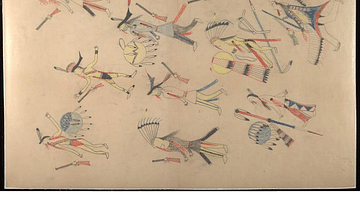

The murder of a white family near Acton, Minnesota, by a party of Indian duck hunters in August 1862, precipitated the break. Messengers were sent to every village with the news, and at the villages of Little Crow and Little Six the war council was red-hot. It was proposed to take advantage of the fact that north and south were at war to wipe out the white settlers and to regain their freedom. A few men stood out against such a desperate step, but the conflagration had gone beyond their control.

There were many mixed bloods among these Sioux, and some of the Indians held that these were accomplices of the white people in robbing them of their possessions, therefore their lives should not be spared. My father, Many Lightnings, who was practically the leader of the Mankato band (for Mankato, the chief, was a weak man), fought desperately for the lives of the half-breeds and the missionaries. The chiefs had great confidence in my father, yet they would not commit themselves, since their braves were clamoring for blood. Little Crow had been accused of all the misfortunes of his tribe, and he now hoped by leading them against the whites to regain his prestige with his people, and a part at least of their lost domain.

There were moments when the pacifists were in grave peril. It was almost daybreak when my father saw that the approaching calamity could not be prevented. He and two others said to Little Crow: "If you want war, you must personally lead your men to-morrow. We will not murder women and children, but we will fight the soldiers when they come." They then left the council and hastened to warn my brother-in-law, Faribault, and others who were in danger.

Little Crow declared he would be seen in the front of every battle, and it is true that he was foremost in all the succeeding bloodshed, urging his warriors to spare none. He ordered his war leader, Many Hail, to fire the first shot, killing the trader James Lynd, in the door of his store.

After a year of fighting in which he had met with defeat, the discredited chief retreated to Fort Garry, now Winnipeg, Manitoba, where, together with Standing Buffalo, he undertook secret negotiations with his old friends the Indian traders. There was now a price upon his head, but he planned to reach St. Paul undetected and there surrender himself to his friends, who he hoped would protect him in return for past favors. It is true that he had helped them to secure perhaps the finest country held by any Indian nation for a mere song.

He left Canada with a few trusted friends, including his youngest and favorite son. When within two- or three-days' journey of St. Paul, he told the others to return, keeping with him only his son, Wowinape, who was but fifteen years of age. He meant to steal into the city by night and go straight to Governor Ramsey, who was his personal friend. He was very hungry and was obliged to keep to the shelter of the deep woods. The next morning, as he was picking and eating wild raspberries, he was seen by a woodchopper named Lamson. The man did not know who he was. He only knew that he was an Indian, and that was enough for him, so he lifted his rifle to his shoulder and fired, then ran at his best pace. The brilliant but misguided chief, who had made that part of the country unsafe for any white man to live in, sank to the ground and died without a struggle. The boy took his father's gun and made some effort to find the assassin, but as he did not even know in which direction to look for him, he soon gave up the attempt and went back to his friends.

Meanwhile Lamson reached home breathless and made his report. The body of the chief was found and identified, in part by the twice broken arm, and this arm and his scalp may be seen to-day in the collection of the Minnesota Historical Society.