The Lombards were a Germanic tribe that originated in Scandinavia and migrated to the region of Pannonia (roughly modern-day Hungary). Their migration is considered part of "The Wandering of the Nations" or "The Great Migration", which was a period roughly defined as lasting between 376-476 CE.

Even so, scholars recognize that these migrations may have begun earlier and lasted longer than the traditional dates given. The historian J. F. C. Fuller writes that "The Wandering of the Nations" officially begins "with the crossing of the Danube by the Goths in 376", but there is evidence of such migrations prior to this date (277).

The Lombards are first mentioned in Roman sources in 9 CE by the historian Velleius Paterculus, again in 20 CE by Strabo, and in 98 CE by Tacitus. The most comprehensive early account of their origins is The History of the Lombards written by Paul the Deacon in the late 8th century CE based on an earlier work known as The Origin of the Lombards but, as historian Roger Collins points out, "This is a work that is full of problems for the historian" because "it depends for its information on a variety of sources, not all identifiable and of uneven worth" (198).

Further, Paul the Deacon's work includes accounts which he, himself, labels "silly", and others (such as the prostitute giving birth to seven children at once, one of whom later becomes the Lombard king Lamissio) which he claims should be accepted as fact. Still, historians have relied on Paul's work for the more reliable information it provides on the early history of the Lombards.

They allied themselves with the Eastern Roman Empire against the Ostrogoths of Italy and fought for Rome at the Battle of Taginae against Totila in 552 CE. In 568 CE they left Pannonia en masse and invaded Italy, setting up the Lombard Kingdom under their king Alboin (r. c. 560-572 CE). Their kingdom grew in size and strength until it comprised almost the whole of modern-day Italy; it lasted until 774 CE when they were defeated by the Franks and, afterwards, existed in Italy only as small city-states under other powers. Their name still survives in the modern-day region of Lombardy in northern Italy.

Early History & Alliance with Rome

Paul the Deacon relates how the Lombards were originally a Scandinavian tribe known as the Winnili. The leaders of one sub-group of this tribe were Ibor and Aio who, with their mother Gambara, left the tribe and migrated south, finally settling in the region Paul refers to as Scoringa (near the Elbe River). Paul writes that the Vandals in the area were "coercing all the neighboring by war" and "sent messengers to the Winnili to tell them that they should either pay tribute to the Vandals or make ready for the struggles of war" (8-9). The two brothers determined "that it is better to maintain liberty by arms than to stain it by the payment of tribute" and sent word to the Vandals that they would rather fight than live as slaves. Their problem, however, was that they did not have a very large fighting force and were sure to be outnumbered by the Vandal army.

Paul the Deacon writes that both sides appealed to their chief god, Odin, for victory:

At this point the men of old tell a silly story that the Vandals, coming to Godan (Odin) besought him for victory over the Winnili and that he answered that he would give the victory to those whom he saw first at sunrise. (9)

Gambara of the Winnili then went to Freia (also given as Frigg or Frigga), Odin's wife, and asked her to give victory to her sons in battle. Freia told Gambara that the women of the Winnili should "take down their hair and arrange it upon the face like a beard, and that in the early morning they should be present with their husbands and in like manner station themselves to be seen by Godan from the quarter in which he had been wont to look through his window toward the east" (9). The women arranged themselves in the ranks with their hair tied to look like beards and, the next morning, Odin looked out his window at sunrise and saw them standing ready in the field. He said, "Who are these long-beards?" And then Freia said how, since he had now given the tribe their name, he should also give them the victory, which he did; and so the Winnili became the "Longbeards" which, in time, became "Lombards".

Paul then writes of this tale that "these things are worthy of laughter and are to be held of no account" and claims that the name "Langobards" comes from the length of the men's beards ("Long Beards") which they refuse to cut or trim. Most scholars believe their name derives from one of Odin's names, Langbaror, as the tribe had dedicated themselves to the worship of Odin at some point after leaving Scandinavia.

After defeating the Vandals, the Lombards found little food or resources in the region and, according to Paul, "suffered great privation from hunger" and "their minds were filled with dismay" (10). They therefore decided to move on and, after a number of other adventures (including battles and single combat with various opponents), they settled in the land east of the Elbe, known to Paul the Deacon as Mauringa and corresponding to modern-day Austria. Here they were overpowered by the Saxon Confederacy for a time, until they rose under their king Agelmund (son of Aio) and lived as an autonomous people for the next 30 years.

It is at this point that Paul gives his account of the prostitute who gave birth to seven unwanted children and threw them into a fish pond to drown. King Agelmund stops at the pond to give his horse water and finds one of the children still living, so he draws him out and raises him as his own son. This was Lamissio who, "when he had grown up, became such a vigorous youth that he was also very fond of fighting, and after the death of Agelmund, he directed the government of the kingdom" (13-14). Lamissio's rise to power came after a raid by the Bulgarians in which Agelmund was killed and his daughter was kidnapped.

Lamissio rallied the Lombards, defeated the Bulgarians, and rescued the princess. Other kings, such as Lethu, Hildeoc, and Gudeoc followed Lamissio and, possibly because of overpopulation and lack of resources, or possibly because of conflict with the Huns, they moved on in c. 487 CE to the Danube region following Odoacer of Italy's destruction of the Rugii tribe who lived there.

It is at this point, roughly, that they came to the notice of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire who invited them to Pannonia to defend the region against the Gepid tribe or, according to other sources, they were a part of the Thuringian (Goth) hegemony, which broke apart and they migrated to Pannonia on their own. This is the period, c. 526 CE, when the first "definitely historical king, Wacho" reigned over the Lombard tribe (Halsall, 398). They defeated the Heruls, who lived in Pannonia, and took over their ancestral lands.

Allies & Enemies of Rome

Under their king Wacho and, later, Audoin (reigned 546-560 CE), the Lombards prospered in Pannonia. Audoin died in 560 CE and was succeeded by his son Alboin (reigned 560-572 CE), one of the greatest Lombard kings. Alboin, according to some sources, felt the best way to defeat the Gepids was by allying himself with King Bayan I of the Avars (reigned 562/565-602 CE) and defeated them in battle in 567 CE, killing their king Cunimund and taking his head as a trophy which he later turned into his wine cup.

Sources differ on these details, however, and it may have been Bayan I who suggested the alliance and who killed Cunimund, later giving the skull to Alboin to celebrate their victory. Once the Gepids were subdued, however, the Avars gained the upper hand in the region owing to the deal Alboin had made with Bayan I prior to battle. Bayan I had insisted that, should they defeat the Gepids, all Gepid land and wealth would revert to the Avars, not the Lombards. Why Alboin agreed to these unfavorable terms is not known. With Gepid land under their control, the Avars began to exert more power than the Gepids had ever commanded. Scholar Guy Halsall writes:

Eventually, in spite of victories over the Gepids, in the third quarter of the fifty century the Lombards found themselves once again in the position of a losing political faction when the Avars, moved to the Danube region by the eastern Romans, emerged as the area's dominant power. (399)

Alboin then married Rosamund, the daughter of king Cunimund, in order to tie the Lombards and Gepids in alliance against the Avars but, by this time, the Avars had grown too powerful and the Gepids too weak; Alboin felt it more prudent to leave the region. A large number of Lombard troops had served in the imperial forces under the general Narses in Italy, performing particularly well in combat at the Battle of Taginae in 552 CE, where Narses defeated the Ostrogothic king Totila and re-claimed Italy for the empire. These soldiers still remembered Italy as a green and fertile land, and either they suggested a migration to Alboin or, according to other sources, Narses himself invited them to Italy (this later claim is routinely contested). Whatever his motivation, in 568 CE, Alboin led the Lombards out of Pannonia and into northern Italy.

Invasion of Italy & Death of Alboin

Alboin found the country relatively deserted and, for the most part, took city after city with little or no opposition from imperial forces (the great exception being Pavia which took a siege of three years to conquer). By 572 CE, Alboin had conquered most of Italy, establishing his capital at Verona until Pavia had been taken. He divided the country into 36 territories known as "duchies", each presided over by a duke who reported directly to the king.

While this made for efficient government from a bureaucratic point of view, it left too much power in the hands of the individual dukes, and regions either prospered or suffered, depending on the quality of their particular duke. Alboin ruled effectively from Verona but, as he was more concerned with securing his borders against the Franks and fending off the eastern empire, he left the affairs of government to these subordinates, which resulted in a lack of cohesion between the territories as each duke, naturally, wanted the best for his particular region.

The Lombard Kingdom, therefore, was in a particularly vulnerable state in 572 CE when King Alboin was assassinated by conspirators led by his wife Rosamund. According to Paul the Deacon, she had never forgiven Alboin for killing her father and convinced Alboin's foster brother, Helmechis, to murder him. Other sources on Alboin's assassination (such as Gregory of Tours or Marius of Aventicum) provide different details, but all agree that the plot was set in motion by Rosamund who had Alboin killed to avenge her father.

Paul the Deacon provides the famous story of Alboin forcing Rosamund to drink from the cup he had made from her father's skull, inviting her "to drink happily with her father." This insult, Paul, claims is what finally drove Rosamund to have her husband killed. Following the loss of their king, the various Lombard territories became even less unified, fighting with each other until they were threatened by the outside forces of the Franks and the eastern empire.

The Byzantine Empire had expended enormous amounts of money to win back Italy from the Ostrogoths following the death of Theodoric the Great in 526 CE. Between 526-555 CE the eastern empire was almost constantly at war with the Ostrogoths of Italy, often employing the Lombards against them. It was a blow, therefore, to have their former allies now occupying the lands that the imperial forces had fought so hard to reclaim.

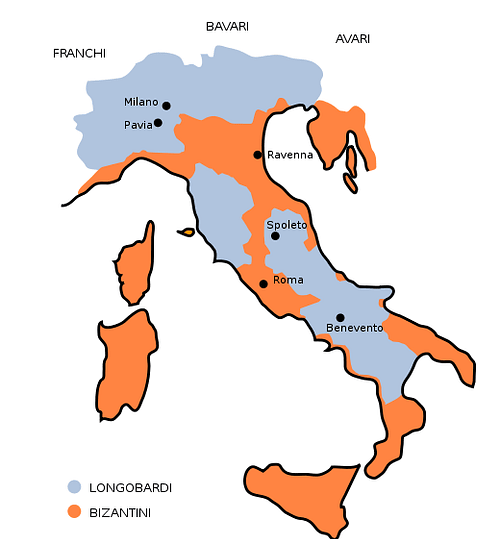

In c. 582 the emperor of the Byzantine Empire, Maurice, established the Exarchate at Ravenna whose purpose was to reclaim Italy from the Lombards. The Exarchs were military commanders whose role would be to organize the populace and equip an army. The people of Italy, however, who still remembered the exorbitant taxes of the empire, were not interested in seeing a return of imperial rule and had even less interest in seeing their tax money go to finance more wars of the empire instead of going to improvements in their own land. The Exarchate, therefore, was ineffective and came to nothing.

Alboin's Successors & The Lombard Kingdom

The threat of an imperial force, however, did prompt the Lombard dukes to stop fighting amongst themselves and choose a king, Authari, in 586 CE. Authari defeated the Byzantine forces which finally rallied against the Lombards in 586 CE but lost lands to them in another battle the next year. In an effort to strengthen his position, he initiated a marriage with the daughter of one of the Frankish kings, Childebert II, but negotiations fell through, and Childebert married his daughter to a Visigoth king. The Franks, who had long been hostile to the Byzantine Empire, now allied themselves with it against the Lombards and, in 590 CE, mounted a full-scale invasion of Italy, taking a number of important cities.

Authari then married the daughter of a Bavarian duke, Theodelinda, in order to secure some kind of alliance against the forces of the Franks and Byzantines. Before he could affect any kind of military engagement, however, he died in 590 CE and was succeeded by his relative (possibly nephew) Agilulf (reigned 590-616 CE) who married his widow. Agilulf was a much more effective ruler than Authari. He secured a peace with the Franks, strengthened his borders, and then re-organized the structure of the government to reduce the power of the Lombard dukes and bring the whole of Italy more tightly under his control.

The Byzantine Empire was fighting off the Avars and Slavs in the Balkan region and trying to repel the Persians in Anatolia and had no resources to spare for further campaigns in Italy. Agilulf, therefore, was able to reign in relative peace. The Lombards were primarily Arian Christians, while much of the populace was Trinitarian (Roman Catholic) and yet, as Collins writes, the division between Arians and Catholics, which caused so many problems in other kingdoms and at other times, does not "seem very contentious. There are no accounts of theological debates or of confrontations over the ownership of churches" (215). Agilulf, an Arian, patronized Catholic shrines and agreed to have his sons baptized as Catholic, at his wife's request. Collins further notes that:

Despite the abusive language used about them in such texts as the imperial letters to the Frankish king, the Lombards were by no means the barbarians they have sometimes been made out to be...they were said to be Christians by the late fifth century, and their common adhesion to Catholicism, as opposed to the Arianism of the Gepids, was used as a diplomatic counter in their relations with the Empire in the time of Justinian. Admittedly, this cannot be true of all the people, as in the generation after their invasion of Italy many of them are reported as still being pagans. Furthermore, by the time of Alboin (c. 560-72) some of the Christian Lombards seem to have become Arians. (204)

Still, the kind of sectarian violence which is recorded in other kingdoms (such as that of the Vandals of North Africa) never seems to have posed a problem in the Lombard Kingdom. As their realm became more secure, they started to imitate the customs of the people of Italy as Collins notes: "In material culture they show themselves no different from the Goths or Franks. Their dress and weapons were, like those of these other peoples, strongly influenced by Roman traditions and above all by the styles favoured by the late imperial army" (204). By the time of Agilulf's reign the native customs, dress, and mannerisms of the Lombards had been largely replaced by those of the Romans. They increasingly shed their pagan rituals in favor of Catholic rites and chose Roman names for their children at baptism.

After Agilulf's death, his wife Theodelinda reigned until 628 CE when her son, Adaloald, came of age and took the throne. He was deposed by Arioald, his brother-in-law and a staunch Arian, who objected to the king's Catholicism. Arioald was succeeded in 636 CE by Rothari who is considered the most effective Lombard king to rule between Alboin and the later Liutprand. Under Rothari, the Lombards expanded their holdings in Italy until the Byzantine Empire held only Rome and a few small provinces. The north of Italy was completely dominated by Lombard rule as was the majority of the south. He issued the first written law of the Lombards, the Edictum Rothari, in 643 CE, which codified the laws in Latin. Rothari was succeeded by his son, Rodoald, who was quickly assassinated by political enemies.

Decline of the Lombards & The Frankish Conquest

Following his death, the Lombard Kingdom split between two rulers, one at Milan and the other at Pavia, and the Lombards battled each other as well as encroaching Slavic tribes on the borders. This situation was resolved when Liutprand came to the throne in 712 CE and reigned until 744 CE. Liutprand is generally regarded as the greatest Lombard king since Alboin. He increased the Lombard Kingdom beyond even what Rothari had accomplished and allied himself securely with the powerful Franks against all enemies. His reign was characterized by security and prosperity, but this good fortune would not last long beyond his death.

His successors were generally weak and greedy men or simply ineffective rulers. The last king, Desiderius, succeeded in taking Rome and driving the Byzantines from Italy but, when he threatened Pope Hadrian I, Charlemagne of the Franks interceded, breaking the Frankish-Lombard alliance, and defeated Desiderius in battle in 774 CE. Charlemagne then seized the lands of the Lombards and so ended Lombard rule in Italy. Some territories under surviving Lombard dukes remained, but there was no longer a central Lombard government, and the people, with their culture, were absorbed into the kingdom of the Franks.