The London Blitz was the sustained bombing of Britain's capital by the German and Italian air forces from September 1940 to May 1941 during the Second World War (1939-45). The objective was to bomb Britain into submission, but despite almost 100,000 civilians being killed or injured in the nightly raids, Londoners resisted, and the war went on.

Hitler's Objectives

Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939 following the latter's invasion of Poland. By mid-1940, Germany had marched through the Low Countries, British forces had abandoned the Continent in the Dunkirk evacuation, and France had fallen. A German invasion of Britain (Operation Sea Lion) looked imminent, and it would surely be preceded by the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) attacking Britain to gain air superiority. Cities might also be threatened, just as they had been in the First World War (1914-18) when German Zeppelin airships had attacked London.

At first, the Luftwaffe concentrated on trying to destroy the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the air and on the ground by bombing airfields. When this strategy proved unsuccessful, and the RAF effectively won the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe changed tactics. Bombing London and other cities became the new objective, as specified in a directive from the leader of Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler (1889-45): "...for disruptive attacks on the population and air defences of major British cities, including London, by day and night" (quoted in Dear, 108).

The Luftwaffe was now intent on destroying Britain's material supplies and crushing civilian morale by targeting the docks in London's East End, key industrial sites, power stations, railway terminals, and other ports. London was just 30 minutes from Luftwaffe bases and an easy target thanks to the highly visible (even at night) dramatic bends in the River Thames. The strategy, in the end, failed to weaken Britain's resolve, but hundreds of thousands of civilians would first have to live through a nightmare of bombing that lasted nine months with long periods when raids came every single night.

Evacuations

Fearful of a great loss of life during the air war, both from conventional bombing and the use of poisonous gas, the government had already strongly encouraged the evacuation of children in wartime Britain to reduce casualties. Around 6 million children and mothers did evacuate to smaller towns and rural communities, four million as part of the government's Operation Piped Piper evacuation scheme, which included sending some children to North America, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. One million, that is around half the children of London, were evacuated, although a significant proportion returned home during the initial quiet months of the war, the so-called Phoney War.

The decision to evacuate was a difficult one for parents, and the experiences of the children depended largely on the kindness and tolerance of the volunteer foster parents who took them in, some for several years until the war ended. The experience contributed to a greater social mixing in Britain with all parties seeing how other people lived and witnessing habits they would otherwise have not imagined. There were also lasting psychological effects for many, and the study of just how children were mentally affected, both those who were evacuated and those who stayed at home to endure the bombing, launched a new and lasting emphasis on this side of child welfare.

Children and young mothers were not the only evacuees. Many adults left cities just for the night and returned the next morning, a phenomenon known as 'trekking'. Artworks, too, were removed from danger. The Parthenon sculptures and other treasures of the British Museum were packed into cases and kept in an underground station on the Piccadilly line. Public art and statues which could not be moved were encased in packing and sandbags, although Lord Nelson on his high pedestal in Trafalgar Square was left to glare defiantly at the incoming planes.

Civil Defence

Britain had an integrated air defence system called the Dowding System after the air chief marshal of that name. The system, managed by the RAF's Fighter Command, involved code-breakers interpreting enemy communications, radar stations and volunteer observers plotting aircraft movement, and control centres to distribute information to alert the front line of barrage balloons, searchlights, anti-aircraft guns, and fighter planes like the Supermarine Spitfire. Fighter Command also alerted the Air Raid Protection (ARP) wardens and local police so that civilians could take to the air raid shelters.

The Dowding system worked well but, it did not mean that bombers did not get through to drop thousands of bombs on London and elsewhere. London had around 1,000 barrage balloons in 1940, typically operated by the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). The number of anti-aircraft guns (just 92 at the Blitz's start) was insufficient, but they increased as it became clear that London was a specific target. In any case, due to the limited technology of the period, both balloons and guns were rarely capable of incapacitating enemy planes, although they did act as a deterrent to aircraft flying lower to make their bombing more accurate. Another defence problem was that the RAF fighters often had to deal with enemy fighters like the Messerschmitt Bf 109 before they could attack the bombers. Although unable to make London immune to bombing, the defence system did prove its value in the longer term as the air war became one of attrition.

The Bombers

London was first hit from the air when a small group of Heinkel He 111 aircraft bombed the city on 24 August 1940. They had been sent to hit an oil terminal but mistakenly hit the city, thus beginning a tit-for-tat bombing of civilian areas that escalated for the remainder of the war. The RAF bombed Berlin on 25 August, and the Luftwaffe sent 300 bombers to hit London on 7 September. The bombing continued until May 1941, and it was the British press that first called this sustained attack 'the Blitz'. The German aircraft were based in occupied France and the Netherlands. The Italian air force, operating from occupied Belgium, also took part in the Blitz. Sometimes just seven planes attacked London, in other raids there were 400, but the average raid involved around 250 aircraft.

The bombing was usually carried out at night since the bombers remained vulnerable to RAF fighter attacks and were much more exposed to anti-aircraft shells during the day. There were some daylight raids, particularly when there was cloud cover. The consequence of focusing on night raids was that bombing was very inaccurate. The Luftwaffe dropped explosive bombs to ruin buildings and then incendiary bombs to start fires that might spread to neighbouring structures. The incendiary bombs were so light that they often drifted badly and hit unintended targets. The East End of London, where the docks were located, was a particular target.

Peter Stahl, a crew member of a Junkers Ju 88 bomber, noted in his diary his experience of bombing London:

It must be terrible down there. We can see many conflagrations caused by previous bombing raids. The effect of our own attack is an enormous cloud of smoke and dust that shoots up into the sky like a broad moving strip.

(Holland, 731)

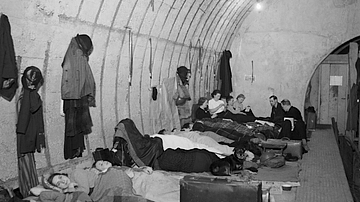

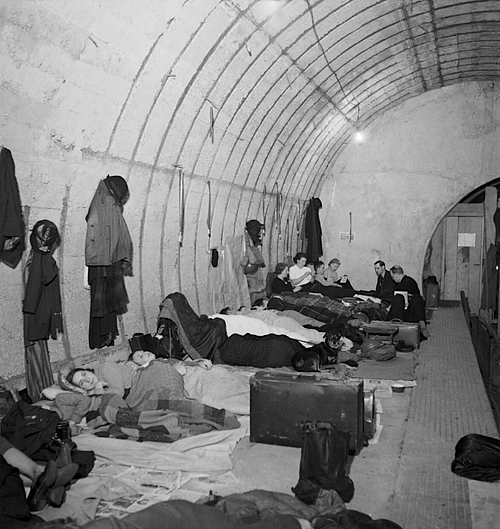

Taking to the Shelters

Civilians were made aware that an air attack was 12 minutes away by a siren. The safest place was in shelters like the stations of the London Underground, although even here bombs did occasionally cause loss of life. One had to bring one's own bedding, there was plenty of noise from chatter and children running about, and the sanitation was limited, but this did not put off over 150,000 people who chose to spend the nights in the stations.

For those not near a Tube station, there were shelters built in the street. Community shelters were, at first, short in number and poorly built, but they improved as the Blitz went on, and many were supplied with toilets, beds, and a small canteen. London had around 5,000 community shelters.

The government had initially favoured a policy of not encouraging people to congregate in shelters since this meant a direct hit would bring a higher loss of life than if people were dispersed. Certainly, shelters were not immune to the attacks. In one infamous episode, the Kennington Park Shelter – a long trench lined with concrete – was struck by a bomb, which killed 47 people. Community shelters in the cellars of buildings like schools and town halls could be safer, but there were cases where the building collapsed on top of the foundations and trapped people underneath.

Businesses were obliged by law to provide some sort of shelter for their workers (who worked day and night shifts) and were given government funds to do so, but, again, the ability of such shelters to withstand bombing varied greatly.

Another option was to have an Anderson shelter in one's garden. Made of sheet metal and packed around with soil, an Anderson shelter could resist close calls, showers of shrapnel, and flying debris but not, of course, a direct hit. The shelter measured 6 ft by 4 ft 6 in and was 6 ft high (1.8 x 1.4 x 1.8 m). They were meant to accommodate four people or six at a push. Around two million shelters were distributed free of charge to low-income families with priority given to areas considered most vulnerable to attacks.

Despite all these provisions for shelters, the most popular place to see out an air raid remained people's cellars if they had them or, failing that, under a steel table known as a Morrison shelter or, most popular of all despite the danger, simply gathering under the stairs. Most raids lasted most of the night. People were informed that a raid was finally over by sirens ringing a steady note. Eventually, the authorities stopped the sirens in favour of a calmer warning system using the ARP wardens. The people themselves became tired of leaving their homes night after night, and by November 1940, only 40% or so of Londoners were going to the public shelters for refuge.

Volunteer Services in the London Blitz

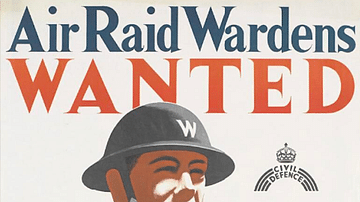

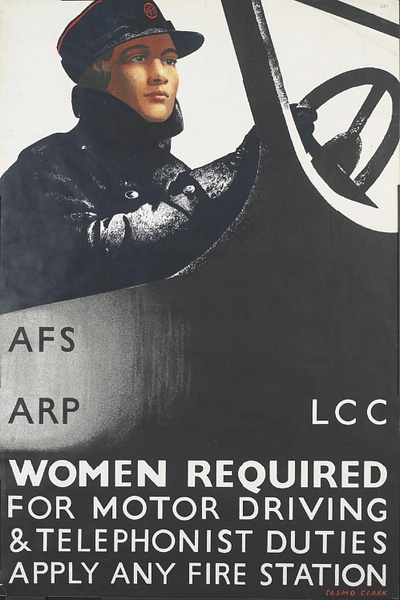

London dealt with the air raids thanks to an army of tens of thousands of volunteers and workers in key roles such as the fire service and ARP service. ARP wardens ensured the blackout was enforced, the policy that non-essential lights should not be seen outdoors and help enemy aircraft. Air raid wardens guided people to shelters, informed the authorities where the bombs were falling, helped dig people out of ruined buildings, and formed stretcher units. In London, there were around ten warden posts to every square mile (2.6 sq. km), each post usually having five wardens.

The regular fire service could not have coped alone with the number of incidents in the Blitz. In one raid, for example, on the night of 29 December 1940, the city's fire services had to deal with over 1,500 separate fires. Accordingly, the regular fire service was supplemented by male and female volunteers of the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS). The public often helped to put out fires using buckets and stirrup pumps.

There was also a compulsory scheme of firewatchers (aka Fire Guards), people who looked out for incendiary bombs and ensured they did not start huge blazes. Another key volunteer service was the Women's Voluntary Service for Civil Defence (WVS). WVS volunteers operated mobile canteens, which were much appreciated by those made homeless and other volunteers working in the streets like the firefighters. WVS volunteers also operated rest centres, which distributed food and clothing to those who had lost everything they possessed. The feelings of the destitute are summed up by Lily Merriman, who lost her house to a bomb: "We felt like refugees. I used to feel dirty. We didn't see any of our old neighbours any more. We was shifted, and that was it" (Levine, 30).

Other key services that performed essential duties included the bomb disposal squads who dealt with unexploded munitions (UXBs) – and there were lots of them since around one in ten bombs failed to explode on impact. The Home Guard, male volunteers who were too young or too old to join the regular armed services, helped out in any way they could during the raids, particularly in rescue work. Finally, there were all sorts of volunteers in the medical services, acting as stretcher-bearers, ambulance drivers, and staffing first-aid centres. The logistics of organising the services to best respond to where they were required was another huge task and this work was often done by volunteers who staffed control centres, distribution centres, and advice bureaus.

Britain Can Take It

After a raid, Londoners went on with their daily lives as best they could, as explained here by Phyllis Warner:

One of the oddest things about our everyday life is its a mixture of ruthless horror and every-day routine. I pick my way to work past the bomb craters and the shattered glass, and sit at my desk in a room with a large hole in the roof (a block of paving stone came through). Next to a house reduced to matchwood, housewives are giving prosaic orders to the baker and the milkman. Of course, ordinary life must go on, but the effect is fantastic. Nobody seems to mind the day raids. It is the nights which are like a continuous nightmare, from which there is no merciful awakening. Yet people won't move away. I know that I'm a fool to go on sleeping in Central London which gets plastered every night, but I feel that if others can stand it, so can I.

(Gardiner, 48)

As the destruction affected more people, the monarchy and leading politicians visited bombed-out homes, and the propaganda branch of the UK government put up posters with slogans like "Britain Can Take It".

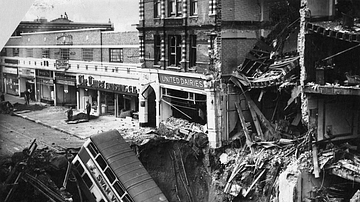

Counting the Cost

In May 1941, Hitler decided to halt the Blitz and instead attack the USSR (Operation Barbarossa). Germany continued to bomb Britain throughout the war, albeit on a much smaller scale. Many British cities had also been badly battered by the Luftwaffe, notably Coventry. The bombing resulted in 60,000 civilian deaths and another 140,000 injured (Dear, 109). Of these figures, 15,000 children were killed or injured. Civilian deaths in the Blitz totalled over 42,000 with another 50,000 injured. Up to the autumn of 1942, more British civilians were killed by bombs than British military personnel. 750,000 civilians were made homeless.

Familiar landmarks also suffered. The House of Commons burnt down, Westminster Abbey was badly damaged, Madame Tussaud's had its wax figures blown to bits (although Hitler's model only suffered a chipped nose), the British Museum lost 250,000 books in a fire, and the Natural History Museum also suffered significant damage. There were survivors. St. Paul's Cathedral was damaged but, miraculously, a massive bomb that fell next to the façade failed to explode. The Tower of London escaped with a minor blow to one of its bastions. Big Ben's clock tower suffered superficial damage when a bomb ripped right through it, but the trusty old bell struck the right time anyway a few minutes after the strike. As Big Ben rang out, keeping time throughout the Blitz night after night, Londoners imagined they could hear in its reassuring echoes, "We can take it!".

The Luftwaffe conducted 85 major operations against London and dropped 24,000 tons of high explosives. The Luftwaffe lost around 600 bombers, but this was a mere 1.5% of the total aircraft sorties. Many factories important to the war effort were struck, but repairs were made and production was not greatly affected in most cases. The government's decision to introduce rationing in wartime Britain meant the disruption to food supplies from the East End docks was overcome. Damage to transport infrastructure was repaired quickly in most cases. In the end, London, then twice the size of Berlin and 17 times bigger than Paris, was simply too big to bomb into submission. Britain gained a terrible revenge for the Blitz with the Allied bombing of Germany, but London would once again face air attacks in the final year of the war when Germany sent almost 10,000 V-weapons (unmanned flying bombs) to hit the capital.

The Blitz Myth

After the war, and even during it, there arose the idea that the Blitz was an episode in British history that was a source of great pride. It was a time when people pulled together and displayed what became known as the 'blitz spirit', a united resistance against a common foe. Modern revisionist historians have been keen to show some of the holes in this idealised view of the Blitz. It is certainly true that there were many episodes of crime such as looting of bombed houses and shops, there was a very negative reaction against other nationalities and Jews, and there were episodes of social discontent and anger at the government's lack of organisation, particularly in providing safe public shelters. However, these negative aspects did not concern the majority of people. Those who were there – civilians, armed forces personnel, volunteers, and politicians – all too frequently describe a palpable sense that everyone was in the same boat and sharing a unique and terrible experience. This was perhaps epitomised by the determination of the British Royal Family to remain in London and, when Buckingham Palace suffered several direct hits, by Queen Elizabeth stating, "I'm glad we've been bombed. Now I feel we can look the East End in the face." (Ziegler, 121)