Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455 CE) was an Italian Renaissance sculptor and goldsmith whose most famous work is the gilded bronze doors of the Baptistery of Florence's cathedral. These doors, which took 27 years to complete, were so impressive that Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE) famously described them as the 'Gates of Paradise', a name which has stuck ever since. Another major contribution to the history of art is Ghiberti's autobiographical Commentaries, an invaluable record of the Renaissance art world in the mid-15th century CE and the oldest surviving autobiography by a European artist.

Influences & Techniques

Lorenzo Ghiberti was born in Florence in 1378 CE, his given name being Lorenzo di Cione di ser Buonaccorso. He began his career as a goldsmith but he eventually built a reputation in Florence for his masterly skills in bronze sculpture work, then an expensive and much appreciated medium. Ghiberti did his own casting (not all famous artists did) using the direct lost-wax technique, that is creating a wax model with a clay core which was then covered in clay and baked in order to melt out the wax so that the space left could then be filled with melted bronze. However, the part of the process Ghiberti really showed his mastery of metal was in his ability to 'chase' or finish a cast piece, that is to use files, chisels and pumice stone to remove imperfections and bring the metal to shining life.

Inspiration for what to do with these craft skills came from Ghiberti's studies of past and present art. The sculptor was a keen student of the surviving art from antiquity and especially classical artist's preoccupation with human anatomy and proportion. He even had his own small collection of antique pieces. Other influences came from such renowned sculptors as his fellow-Florentine Donatello (c. 1386-1466 CE), who had actually been an assistant to Ghiberti early in his career. In addition, Ghiberti took ideas from the prevalent International Gothic Style and those metalworkers he had contacts with from northern Europe, particularly German craftsmen.

The Gates of Paradise

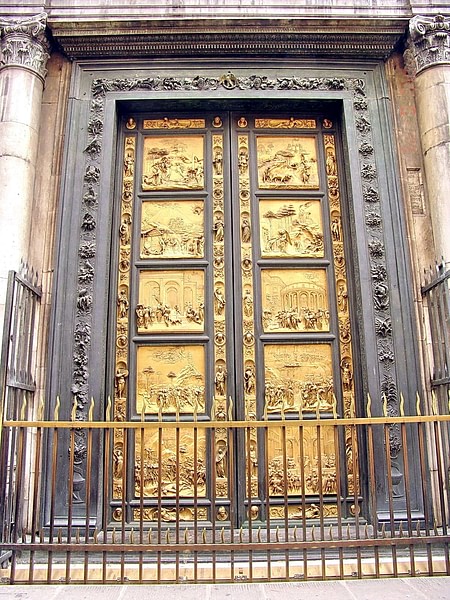

Florence's Baptistery of San Giovanni is a massive octagonal building with a pyramid roof, which stands opposite the main facade of the city's cathedral. First built in the 4-5th centuries CE, the Baptistery was remodelled in the 11-13th centuries CE and given its distinctive green and white marble exterior. The Baptistery has three doorways, and Ghiberti was commissioned to produce the (now) north doors, which show stories from the New Testament. Ghiberti had beaten six other artists, including fellow Florentine sculptor Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446 CE) in a competition in 1401 CE to see who would make these doors. These doors alone would take over 20 years to complete and, in the end, consisted of 28 panels, 74 slim border panels, 48 heads, and another three broad outer borders. The south doors, meanwhile, were created by Andrea Pisano and show scenes of John the Baptist and the Virtues.

It is the east doors, though, that have captured the public imagination. These doors were commissioned by the Arte dei Mercanti in 1425 CE. The work necessitated the creation of a specialised workshop and many noted Renaissance artists would pass through its doors over the years. One big-name artist to be involved was Michelozzo di Bartolomeo (1396-1472 CE) who acted as foreman for the project for some years and he may well have had an influence on the architectural elements of some of the panels. The doors were not finished until 1452 CE.

The doors are each composed of five gilded bronze panels, which show scenes from the Old Testament. Each panel measures approximately 80 x 80 cm (31.5 x 31.5 inches). Around the panels is a frame which contains representations of famous figures from the Bible and contemporary artists. There are even the heads of Ghiberti and his son Vittorio.

The art historian K. W. Woods gives the following technical explanation of how the panels were cast:

Ghiberti cast some figures separately using more fluid bronze and joined them onto the main panel. All of the reliefs were then fire gilded: the bronze surface was covered with a paste of ground gold mixed with mercury and fired at a low temperature so that the mercury burned off, leaving the gold melted and fused with the bronze surface without melting the sculpture. (121)

The main panels show the following:

Left door, top to bottom

- The creation of Adam and Eve, their fall from grace and expulsion from Paradise.

- Noah offering a sacrifice after leaving the ark and the drunkenness of Noah.

- Scenes from the lives of Esau and Jacob.

- Moses receiving the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai.

- The battle against the Philistines and David killing Goliath.

Right door, top to bottom

- The work of the first men and the story of Cain and Abel.

- The angels before Abraham and the sacrifice of Isaac.

- The story of Joseph and his brothers.

- The people of Israel in the River Jordan and the fall of Jericho.

- Solomon meets the Queen of Sheba.

The panels contain figures rendered in such high relief they are almost completely in the round. Each panel has clever devices of perspective, which give the illusion of real depth in scenes which are quite complex with multiple areas of action. The panel showing the story of Joseph (son of Jacob) is a particularly fine example of Ghiberti's skill at rendering depth with the double layer of receding architectural features behind the crowd of foreground figures. Other tricks include diminishing the size of the figures in the various scenes and using high relief in the foreground and shallow relief behind. Similar effects are achieved in the Abraham panel using mountain terrain, trees, and the foreshortening of figures (see especially the donkey in the foreground). As the artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574 CE) noted, Ghiberti "showed such invention, order, manner, and design, that his figures appear to move and to have souls" (Woods, 103). The Florentine authorities were so impressed with the results of their commission that they had Ghiberti's first set of doors moved to the north side so that the new ones could take the best position facing the cathedral.

When the famed sculptor and painter Michelangelo saw Ghiberti's doors he described them as worthy for the gates of Paradise, and this name has been used to describe them ever since. There is an additional connection with paradise as 'paradiso' was the name Florentines used to refer to the space between the Baptistery and the cathedral because the latter was used as the last resting place of important figures. Ghiberti's doors would secure his position amongst the finest of Renaissance artists. To ensure the sculptor's greatest work survives for future generations the panels were cleaned and moved to the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo in Florence. Replicas are now in their place on the Baptistery doors.

Other Works

During the second decade of the 15th century CE Ghiberti was busy in other areas, notably creating a trio of larger than life-sized statues for Florence's Church of Orsanmichele. It was unusual to cast such large figures in bronze, and Ghiberti had to accept financial liability if his ambitious plans went wrong. The c. 1415 CE bronze cast Saint John the Baptist is often taken as the finest of these figures, although his Saint Mathew (c. 1412 or perhaps c. 1423 CE) is captivating for his poise and gesture similar, one might imagine, to an orator in the Roman Senate. The third figure is Saint Stephen, created between 1426 and 1428 CE. Each of the statues is over 2.5 metres (8' 4”) in height. Ghiberti's attention to detail in these figures can be seen in the use of silver inlay for the eyes (only revealed after restoration), and this despite the distance from the viewer and the niche high in the wall where the original statues were placed. Those original figures now reside in Museo di Orsanmichele while faithful replicas stand in the outdoor niches.

Another project in Ghiberti's busy schedule was to build a new tomb for Florence's first bishop, Saint Zanobi, a work which had begun in 1409 CE under other artists and which was not completed until 1428 CE. In demand everywhere, Ghiberti was commissioned to design a new baptismal font for Siena's cathedral in 1414 CE. The impressive marble font and basin was given six bronze relief plaques for its base, and Ghiberti executed one of these, a scene showing the baptism of Christ, completed by 1427 CE. Donatello would produce one of the other plaques in the set which each measure around 62 x 63 cm (24 x 24 inches). There was a great rivalry between such cities as Florence and Siena and so it is no surprise that civic authorities should try and poach the most renowned artists from ongoing projects in rival cities.

In 1418 CE, Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi once again faced off to win the right to execute an important public project, this time the dome of Florence's Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. Both men had limited architectural experience but both submitted drawings and wooden models. Brunelleschi won the competition, but the Florentine establishment insisted on Ghiberti's involvement too. Not best of friends since the Baptistery doors competition, it was said that Brunelleschi took several days off sick in the early stages of the project, simply to show up Ghiberti for the incompetent architect Brunelleschi thought he was. Ghiberti himself would claim half-credit for the finished dome but he left the project in 1425 CE to go to Venice, which was before construction of the really difficult part got underway. As a consequence, credit must ultimately go to Brunelleschi for the soaring dome.

One of Ghiberti's final works may be a c. 1450 CE Madonna and Child sculpture. Rendered in terracotta and then painted, the half-figure has a reclining Eve in the base below. It is now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, USA. The sculpture is of interest as an example of how a pose could be repeated in many different works. In this case there are around 40 surviving examples. A workshop like Ghiberti ran would have produced such model poses for other artists and assistants to copy in different mediums. The piece is also interesting as the solid base suggests it was meant to stand alone on a piece of furniture and so it is an example of art for private enjoyment.

The Commentaries

Around 1450 CE, Ghiberti wrote his Commentaries (Commentarii), which is the first surviving autobiography by a European artist. Never before had an artist been the subject of a genre previously reserved for rulers and saints. This was a sign of the times: artists were no longer considered mere craftworkers as there was an obvious intellectual element to their work as they studied the past and considered such theories as mathematical perspective. Further, art was becoming an essential and important element in how a city or state viewed itself. More than just a biography, though, the work covers the lives and works of many other artists from antiquity to Ghiberti's contemporaries and so is an invaluable historical record of the past and the early Renaissance period. In the work, Ghiberti deplores the destruction of the art of ancient Rome and Greece by the Christian Church but takes heart from the revival in interest in antiquity and the rejuvenation of art in general, which was begun by such painters as Giotto (b. 1267 or 1277 - d. 1337 CE). Lorenzo Ghiberti died in Florence in 1455 CE; one wonders if he ever made it to Paradise and what he thought of the entrance gates.