Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (l. 1747-1793) was a French noble of royal blood. He was the head of the House of Orléans, a cadet branch of the royal Bourbon dynasty, and was a cousin of King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792). Despite this, Orléans supported the French Revolution (1789-1799) and voted for Louis XVI's execution in 1793.

Through marriage and inheritance, Orléans was one of the richest men in France. He used his riches to renovate the Palais-Royal, his Paris residence, which he then opened as a public forum for all French citizens, no matter their social status. It was in the cafés and gardens of the Palais-Royal that the French revolutionaries often met, sharing their visions of a better France. Orléans expressed support for a weakened, constitutional monarchy and took an active role in revolutionary politics, even becoming a member of the radical Jacobin Club. After the abolition of the monarchy in 1792, he relinquished his noble titles and adopted the name Philippe Égalité.

His popularity did not last, and he was met with scorn when he voted to execute his cousin Louis XVI, a move that came off as dishonorable and opportunistic. Orléans himself was guillotined on 6 November 1793. Aside from his revolutionary activities, Orléans is best known for being the father of Louis Philippe I, King of the French (r. 1830-1848), who reigned as France's last king and penultimate monarch during the July Monarchy.

Early Life

Louis Philippe Joseph d'Orléans was born on 13 April 1747 at the Château de Saint-Cloud, 3 miles west of Paris. His father was Louis Philippe I, Duke of Orléans (l. 1725-1785), a powerful French prince who was the most senior member of the French court at Versailles after the royal family. The House of Orléans could trace its origins back to Duke Philippe d'Orléans (l. 1640-1701), a younger son of King Louis XIII of France (r. 1610-1643) and brother of the Sun King Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715). The House of Orléans was, therefore, a cadet branch of the senior Bourbon dynasty, and its male members stood in line for the French throne. Louis Philippe II's ties to royal blood were strengthened further through his mother, Louise Henriette de Bourbon (1726-1759) a member of another cadet branch, House Bourbon-Conti.

On 6 June 1769, the 22-year-old Louis Philippe married Louise Marie Adelaïde de Bourbon, the 16-year-old daughter of his cousin, the Duke of Penthièvre. Louise Marie was the heiress to one of the largest fortunes in France; this, combined with the already substantial wealth of the House of Orléans, made Louis Philippe one of the richest men in France. Together, the couple had six children: three sons and three daughters. Their eldest son, also named Louis Philippe, was born in October 1773; he would go on to reign as King Louis Philippe I, the only French king to come from the Orléans dynasty.

Extramarital Affairs & Naval Career

Louis Philippe was described by King Louis XV of France as "libertine" and by his mistress Grace Elliott as "a man of pleasure" (Fraser, 66). The duke was a known womanizer, an activity he heartily returned to only months after being married. Grace Elliot was his most famous mistress; author of an eyewitness account of the French Revolution, Elliot would later become the mistress of King George IV of Great Britain (r. 1820-1830) as well. Louis Philippe's other mistresses included one of his wife's ladies-in-waiting, Stéphanie Félicité, Comtesse de Genlis, and Marguerite Françoise de Buffon. Louis Philippe shared several illegitimate children with his mistresses.

His many extramarital affairs ended up being much less scandalous than his military career. In 1776, he was given the rank Chef d'Escadre (squadron commander) as well as a 64-gun ship-of-the-line Solitaire; he had no military experience but was awarded his command due to his royal status. He was put to the test in 1778 when France officially joined the 13 American colonies in their war against Great Britain. On 27 July 1778, Louis Philippe commanded a squadron of ships in the Battle of Ushant, the first major naval engagement between British and French ships during the American Revolutionary War. At a decisive moment in the battle, Louis Philippe failed to take advantage of a gap in the enemy lines, allowing the British fleet to escape. The battle proved indecisive, with no vessels lost on either side.

However, when Louis Philippe returned to Versailles on 2 August, he announced that the battle had been a great French victory and that he himself had played a significant role. He received leave from his cousin, King Louis XVI, to be the one to officially announce the news; upon traveling to Paris he was given a hero's welcome. But when other reports of the battle trickled into Paris, Louis Philippe's true conduct was revealed, and he became a laughingstock. He was ridiculed for abandoning the fleet to rush back to Paris, and aristocrats and commoners alike wondered if he made his blunder in the battle out of ignorance or cowardice.

The stain on his reputation was hard to shake off. Around the same time, he was attending a ball where he was characteristically commenting on the appearances of ladies, one of whom he referred to as "faded". Overhearing the insult, the lady whirled around and retorted, "like your reputation, Monseigneur!" (Fraser, 165). Ultimately, the embarrassing fiasco cost Louis Philippe his military career, as Louis XVI denied his request to join Comte de Rochambeau's expeditionary force to America in 1780. Louis Philippe also later became connected to palace intrigue, involving corrupt ministers. For this, Louis XVI had him temporarily banished from the French court. These two instances were viewed as slights by Louis Philippe, whose animosity toward the Bourbon branch of the family began to sprout.

Palais-Royal

In 1776, Louis Philippe's father granted him ownership of the Palais-Royal, the family's main Paris residence that had once been owned by Cardinal Richelieu (1585-1642). Louis Philippe sought to transform the palace into an extravagant resort that would combine cafés, theaters, shops, and "places of more doubtful recreation" (Schama, 134). He hired architect Victor Louis to work on the project, but he soon ran out of funds, and by 1784, construction was halted. But the next year, Louis Philippe's father died, leaving him the title of Duke of Orléans as well as the family's vast wealth. Louis Philippe (henceforth referred to by his new title, Orléans) used his inherited wealth to continue working toward his vision.

The Palais-Royal was open to anyone, regardless of social class. It became a major center of social life in Paris, the place to be for people from all walks of life. As Schama describes it:

Cafés of every kind flourished, from the staid Foy to the risqué Grotte Flamande. One could visit wigmakers and lace makers; sip lemonade from the stalls; play chess or checkers at the Café Chartres; listen to a strolling guitar-playing abbé (presumably defrocked) who specialized in bawdy songs; peruse the political satires (often vicious) written and distributed by a team of hacks working for the duke; ogle the magic-lantern or shadow-light shows; play billiards or gather around the miniature cannon that went off precisely at noon when struck by the rays of the sun (136).

While the Palais-Royal was staffed with Swiss Guards loyal to the duke (employed primarily to toss out drunks and break up fights), regular police were forbidden from entering the grounds without invitation. For this reason, the Palais-Royal became a major hub for illegal activity and black market deals; it also became a hub for early revolutionary thought. Some in the National Assembly later credited the Palais-Royal with being the birthplace of the Revolution itself. Orléans succeeded in establishing a public forum where people could meet and express themselves; for this reason, he became immensely popular.

Rivalry with the Bourbons

On the eve of the Revolution, Orléans was becoming increasingly radicalized. He had read the works of the philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire and began to speak out against feudalism and slavery. He saw the merits of a more limited monarchy and professed to admire Britain's constitutional monarchy and wanted a similar system for France.

Such beliefs helped drive a wedge between him and his Bourbon cousins; likely, he had not forgotten the perceived slights from Louis XVI either. Along with inheriting the title "Duke of Orléans", Orléans was also the First Prince of the Blood. This meant that should none of the males in the senior Bourbon line produce heirs, the throne would pass to him. Orléans' proximity to the throne must have made it all the more vexing with each new child born to Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, which carried him further away from kingship. At the birth of Marie Antoinette's first daughter in 1778, Orléans appeared to snub the royal family by decorating the Palais-Royal with only modest illuminations. The duke's suspected lust for the throne has been suggested as the true motive behind his support of the Revolution.

Whatever his motives, Orléans began to appeal to the people more and more in the years leading up to the Revolution. During the affair of the diamond necklace, when Marie Antoinette was under scrutiny for reckless spending, Orléans sided with her enemies, even though Orléans was almost as wasteful a spender as she was. Many were happy to gloss over this fact, as in the late 1780s, Orléans made himself more popular by making generous donations to Paris' poor. Once, during the Réveillon riots, his carriage was stopped by crowds of rioters. He waved to them and began tossing out bags of money. These acts helped him cultivate a reputation as a charitable noble, making him look especially good while juxtaposed against the despised Bourbons.

As Orléans showered the poor with money, France's ministers were faced with the problem of mountainous state debt. This dire financial situation forced Louis XVI to convene the Assembly of Notables of 1787, which he hoped would sign off on a series of radical financial reforms. Instead, the assembly insisted that only a gathering of the three estates of pre-revolutionary France, known as an Estates-General, had such a power. Frustrated, Louis XVI dismissed the assembly and took his reforms directly to the Parlement of Paris, a powerful judicial court that had the authority of registering royal edicts. When the Parlement agreed with the Notables, Louis XVI tried to circumvent its authority by issuing a lit de justice, which would force the edicts to go into effect. In this dramatic moment, Orléans himself stood up and challenged Louis XVI's authority by declaring such an action to be illegal and an abuse of royal authority. Stunned, Louis XVI responded by banishing Orléans to his estates and exiling the parlements. But the parlements had the people's support, and Louis XVI realized he had no choice but to recall them and promise an Estates-General for 1789.

Revolution

In early 1789, Orléans was one of the 282 deputies elected to represent the Second Estate (nobles) in the Estates-General of 1789. During the parade held to mark the Estates-General's opening, Orléans was cheered by the same citizens who greeted Marie Antoinette with icy silence. Playing up to his reputation as champion of the people, Orléans chose to mingle with the representatives of the Third Estate (commoners), rather than his own class. When the meeting commenced, the Third Estate refused to validate its own elections, protesting that it had unequal representation; this ground all procedures to a halt.

Louis XVI was prevented from mediating on the issue when the dauphin, seven-year-old Louis-Joseph, suddenly died. As the First Prince of the Blood, the duty fell to Orléans to escort the heart of the dead dauphin to its resting place at the convent of Val-de-Grâce. Orléans refused, claiming his responsibilities as a deputy of the Estates-General prevented him from doing so. The responsibility was carried out instead by Orléans' eldest son, the Duke of Chartres. While the king grieved, the Third Estate reorganized itself into a National Assembly and pledged to deliver a new constitution. At first, the upper estates were hesitant to join them; but after deputies of the Third Estate swore the Tennis Court Oath, Orléans led 47 nobles in joining them. Afterward, the rest of the upper estates joined as well.

In July, the riots that led to the Storming of the Bastille began in the Palais-Royal. Rioters carried busts of the duke and cried out "Vive Orléans" as they took to the streets. Orléans, now a deputy in the National Assembly, continued supporting the Revolution, but some believed he aspired to kingship. This belief led to rumors that he had secretly orchestrated, or at least funded, some of the most vital moments of the early Revolution in an attempt to destabilize Louis XVI's grip on the throne.

Such rumors held that he was behind both the Great Fear of July 1789 and the Women's March on Versailles the following October, when thousands of market women descended on the Palace of Versailles and forced the king and queen to accompany them back to Paris. While there is no evidence Orléans organized either of these events, many believed he did; after a small group of women broke into the palace in the early morning hours of 6 October and tried to murder Marie Antoinette, the queen believed Orléans had instructed them to kill her. This belief was shared by her daughter who later wrote, "the principal project [of the attack] was to assassinate my mother, on whom the Duc d'Orléans wished to avenge himself because of offenses he believed he had received from her" (Fraser, 295).

Whatever Orléans' involvement in these events, the summer and autumn of 1789 saw the peak of his influence. While many in France wished to see a constitutional monarchy with Orléans as king, this notion was dangerous to the plans of Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834), whose control of the Revolution was threatened by Orléans' popularity. To get Orléans out of the way, Lafayette convinced him to go to Britain on state business, promising that, in return for such service, he would lend Orléans political support. Orléans went, reluctantly, and came back months later in time for the Festival of the Federation. However, the duke had been gone for too long and never again enjoyed the same influence that he had in 1789. In 1791 after Louis XVI discredited himself with the Flight to Varennes, there was scattered talk of making Orléans king, but he was no longer popular with the masses, who had not heard much from him in two years.

Philippe Égalité

Despite his fall from fame, Orléans continued to support the Revolution. By 1792, he and his eldest son, the Duke of Chartres, had become members of the radical Jacobin Club. Chartres, and Orléans' second son, the Count of Beaujolais, both served in French armies during the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802), and both fought with distinction at the Battle of Jemappes. On 10 August 1792, the French monarchy was abolished in the Storming of the Tuileries Palace, and France was shortly thereafter proclaimed a republic. In recognition of this, Orléans renounced his noble titles and adopted the name Philippe Égalité. Likewise, the Palais-Royal was renamed Palais-Égalité.

Égalité was elected to the National Convention, the Republic's provisional legislature. Here, he sided with the Mountain, an extremist Jacobin faction headed by Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794) and Jean-Paul Marat (1743-1793). The Mountain's rivals, the Girondins, used this as ammunition to attack the Mountain, claiming that they meant to install Égalité as king. In December, the Convention tried the deposed Louis XVI for high treason; after he had been found guilty, the Mountain wanted him executed for his crimes, while the Girondins sought to spare his life. When the votes were counted on 16 January 1793, Égalité voted for execution, claiming, "all who have attacked or will attack the sovereignty of the people deserve death" (Fraser, 398).

Égalité's vote endeared him to no one, seen as dishonorable and opportunistic. It was the only vote that visibly enraged Louis XVI when he was told, and even Égalité's allies in the Mountain, who had pushed for Louis' death themselves, considered Égalité's vote shameful. Égalité's own son, Chartres, was also horrified; he had been a committed Jacobin and a Republican soldier, but the execution of a king was a step too far. In early April, he and his commanding officer, General Charles-François Dumouriez, abandoned the Republic and defected to the Austrian army.

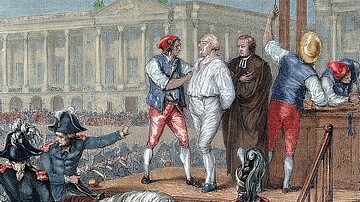

This was Égalité's undoing. Only days before, Égalité himself had supported a motion that condemned anyone presumed of being complicit with "enemies of Liberty". When it was revealed that Chartres had gone over to the enemy, Égalité was almost immediately arrested on 6 April 1793; both of his younger sons and his sister were also arrested. Égalité spent several months imprisoned in Marseille before he was brought to Paris on 2 November to stand trial. On 6 November 1793, he was condemned to death and was guillotined that same day. Powdered and well-dressed, he climbed the steps to the guillotine while members of the crowd taunted him, shouting, "I vote for death!", imitating the words that Égalité had once spoken to condemn his own relative.