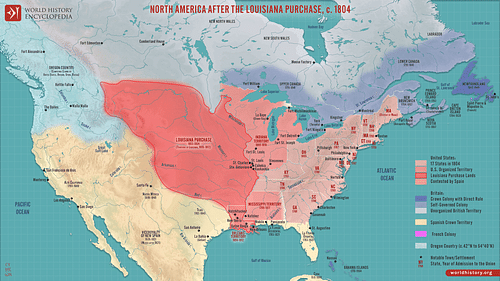

The Louisiana Purchase was a land deal made in 1803, in which the United States purchased 828,000 square miles (2,144,510 km²) of land west of the Mississippi River from France for $15 million, or an average of three cents per acre. The purchase nearly doubled the territorial size of the United States and fostered the westward expansion of the young republic.

Background: The Louisiana Territory

The colony of Louisiana was founded on 9 April 1682, when French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle reached the mouth of the Mississippi River. La Salle erected a cross at the spot, and, in a ceremony performed before his own men and his Native American guides, he proceeded to claim the entire Mississippi Basin for France, naming it Louisiana in honor of King Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715). Shortly thereafter, he returned to France, where he convinced the king to give him control of the new colony. La Salle then embarked on another expedition to fortify the mouth of the Mississippi by establishing another French colony around the Gulf of Mexico. This expedition, however, was beset by difficulties from the start. La Salle was unable to rediscover the mouth of the Mississippi and was ultimately assassinated by mutineers in 1687.

Over the next several decades, scattered settlements began popping up around the Mississippi River. New Orleans was founded in 1718, on the site where La Salle had made his proclamation 36 years earlier, and quickly turned into a rich port city. Timber, agricultural produce, and high-quality furs were shipped down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, where they would be sent on to Europe or New Spain. Despite the wealth generated from New Orleans, the Louisiana Territory as a whole was not highly valued by France. In 1710, Louisiana governor Antoine de La Mothe Cadillac reported that "the people are aheap of the dregs of Canada" and that the colony was "not worth a straw at the present time" (Smithsonian). Therefore, at the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763, France agreed to cede control of the entire Louisiana Territory to Spain. The exact boundaries of ‘Louisiana' were still murky, and the terms of the treaty granted Spain control of all lands west of the Mississippi River. At the same time, France ceded its northern colony of Canada to Britain, thereby unburdening itself of all continental colonies so that it could focus on its much more lucrative sugar colonies in the Caribbean.

Spain enjoyed a tenuous hold on the Louisiana Territory, which it viewed with disinterest, as little more than a buffer between British North America and Mexico. In 1783, the United States won its independence and gained control of the eastern banks of the Mississippi River. This led to rising tensions between the US and Spain, as each nation claimed the right to navigate the Mississippi, which had become a vital waterway for trade. This dispute was settled on 27 October 1795, with the signing of the Treaty of San Lorenzo, also known as Pinckney's Treaty. The agreement gave the Americans the right to navigate the entire Mississippi and allowed American merchants to store goods in New Orleans warehouses. While the treaty de-escalated tensions between the US and Spain, it increased American influence in the region at the expense of Spanish power, which had never been strong to begin with in the Louisiana Territory and was now on the decline.

Then, on 1 October 1800, Louisiana changed hands once again. Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) – who had risen to power in France a year earlier – made a secret deal with King Charles IV of Spain (r. 1788-1808) in the Treaty of San Ildefonso. In it, Spain agreed to cede the entire Louisiana Territory back to France, in exchange for control over the Kingdom of Etruria in Italy, which King Charles wanted to give to his daughter. Napoleon was pleased by the easy acquisition of the Louisiana Territory, seeing it as the first step in re-establishing France as an imperial power in North America. He envisaged Louisiana as a breadbasket of sorts, shipping food and supplies to France's Caribbean colonies of Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Saint-Domingue, all highly valuable for their production of sugar. A significant condition of the Treaty of Ildefonso was that France could not turn around and sell the Louisiana Territory to a third party, as Spain was worried about having a hostile power so close to Mexico. At the time, Napoleon intended to adhere to this condition, although his plans would soon be turned upside down.

Transfer to France

The secret transfer of Louisiana to France became public knowledge in October 1802, when King Charles IV finally signed the royal decree to make it official. A few days later, the Spanish administrator in New Orleans abruptly canceled the Americans' access to the city's warehouses, arguing that the terms of Pinckney's Treaty had expired. This caused much outrage in the United States, as more than half of the country's merchants used New Orleans as the primary port to ship out their produce. Loss of access to the city and the navigation of the Mississippi threatened to deliver a heavy blow to the young republic. Additionally, US President Thomas Jefferson felt anxious at having a new neighbor as insatiably ambitious as Napoleon Bonaparte. The feeble Spanish Empire had been something Jefferson believed he could handle, at one point stating that a continued Spanish presence in Louisiana would be "hardly felt by us" (Wood, 368). Napoleonic France, by contrast, was a rising power whose control of New Orleans was predicted by Jefferson to be a "point of eternal friction with us" (ibid). Indeed, Jefferson was quick to grasp that whichever power controlled New Orleans would forever be in contention with the United States. As he wrote in April 1802:

there is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three eighths of our territory must pass to market, and from its fertility it will ere long yield more than half of our whole produce and contain more than half of our inhabitants.

(quoted in Meacham, 384)

It was clear, therefore, that the United States had to find some way of taking possession of New Orleans. Many Americans, enraged over the loss of access to the city, urged Jefferson to take it by force; one Pennsylvania senator went so far as to draft a resolution calling on the president to raise a 50,000-man army to invade Louisiana and capture the city. These belligerent sentiments were backed up by several newspapers, with one declaring that the United States alone had the right to "regulate the future destiny of North America" (Smithsonian). Jefferson, however, resisted these calls to action. An outspoken Francophile, the president viewed war as a last resort and instead wondered if he could purchase New Orleans from the French. As early as April 1802, when the first rumors of the transfer of Louisiana had reached his desk, Jefferson had contacted Robert R. Livingston, the US ambassador to France, to inquire whether the United States might buy the city. He told Livingston that France might be willing to sell New Orleans for $6 million and, in January 1803, sent James Monroe to Paris as a presidential envoy to help Livingston close the deal.

Napoleon, meanwhile, was experiencing buyer's remorse as his plans for a colonial empire unraveled. The main thorn in his side was the colony of Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti), which had been embroiled in a slave uprising since 1791. Napoleon had planned for Saint-Domingue to be the heart of his colonial empire; by far the most valuable French colony, Saint-Domingue provided France with 70% of its sugar supply. In 1801, Napoleon dispatched an expeditionary army under his brother-in-law General Charles Leclerc to restore French authority over the island by crushing the uprising and overthrowing the revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture. However, the expedition met with disaster. Although the French managed to capture Louverture, they were met with fierce resistance. The French army was also devastated by an outbreak of yellow fever, which killed thousands of soldiers, including Leclerc. By 1803, it was clear that the reoccupation of Saint-Domingue had failed, and with it, Napoleon's dreams of a colonial empire. He believed that the Louisiana Territory was worthless without Saint-Domingue and was now eager to find someone to take it off his hands.

Negotiations

In April 1803, James Monroe arrived in Paris after a long and painful journey. Beset by financial troubles, he had been forced to sell his fine china and furniture to pay for the trans-Atlantic passage, only for his departure to be delayed by a snowstorm and strong winds. Yet Monroe never doubted the importance of his mission, having been told by Jefferson that the "future destinies of this republic" depended on his success. Upon arrival in Paris, he was greeted by Livingston who excitedly told him that the situation had changed. Just days before, Livingston had met with French Treasury Minister François Barbé-Marbois, who had offered to sell not just New Orleans but the entire Louisiana Territory to the United States. Barbé-Marbois offered to sell the territory for $15 million, or three cents per acre. Although Monroe and Livingston had only been authorized to spend up to $10 million, they were certain that this was not an offer they could pass up.

The Americans were quick to enter negotiations, eager to seal the deal before Napoleon changed his mind. In fact, there was no danger of that, as the First Consul was equally as eager to sell. The loss of Saint-Domingue had not only rendered the Louisiana Territory worthless to him but also made it a liability; the longer Napoleon held onto the territory, the more he risked coming into conflict with the United States, a war he neither wanted nor could afford. Napoleon also knew that the sale of Louisiana would nearly double the size of the United States and turn it into a continental power. With this newfound strength and additional resources, Napoleon hoped that the US would be able to rival Britain's maritime supremacy and thereby weaken his arch nemesis. Finally, Napoleon was planning an invasion of England and sorely needed the money to help pay for it.

By 11 April, he had made up his mind to sell the entire territory, telling his foreign minister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand that "I renounce Louisiana. It is not only New Orleans that I cede; it is the whole colony, without reserve…to attempt obstinately to obtain it would be folly" (quoted in Roberts, 324). One night, while Napoleon was soaking in his bathtub, his brothers Joseph and Lucien barged in to plead with him to change his mind, even threatening to publicly oppose the sale. This only enraged the First Consul who rose from his tub, proclaimed he would tolerate no opposition, and then plopped back down, causing a splash that drenched Joseph.

So, with both parties equally enthusiastic, negotiations swiftly commenced. Monroe and Livingston tried to haggle the price down to $12 million, but once Barbé-Marbois indicated that he could go no lower than $15 million, the Americans agreed to that price. The treaty was signed by Monroe, Livingston, and Barbé-Marbois on 2 May 1803 and was backdated to 30 April. To pay for the deal, it was agreed that two banking houses – Baring & Co of London, and Hope & Co of Amsterdam – would provide the cash for the transaction. The US was to pay them back with bonds, which were to be repaid over a 15-year period at 6 percent interest, setting the final price for the purchase at $27 million.

At the time, Monroe and Livingston did not know exactly what they were buying – the exact boundaries of the Louisiana Territory were poorly defined, and borders would have to be drawn up with Britain and Spain. Not to mention the tens of thousands of Native Americans who lived within the territory who would likely not welcome floods of incoming US settlers. Yet, they recognized how monumental the deal had been. "We have lived long," said Livingston, "but this is the noblest work of our whole lives…from this day, the United States take their place among the powers of first rank" (quoted in Roberts, 326).

Boundaries & Ratification

News of the Louisiana Purchase reached Washington, D.C., on 3 July 1803, just before Independence Day. The deal was condemned by some Americans, most notably Jefferson's rivals in the Federalist Party, who denounced the Louisiana Territory as "a great waste, a wilderness unpeopled with any beings except wolves and wandering Indians" (quoted in Wood, 369). However, these detractors were in the minority. Most Americans were ecstatic by the deal, which not only secured the use of New Orleans and the Mississippi but transformed their fledgling republic into a continent-spanning power. "Every face wears a smile, and every heart leaps with Joy," wrote Andrew Jackson, then a minor Tennessee politician, while a Washington newspaper noted the "widespread joy of millions at an event which history will record among the most splendid in our annals" (Meacham, 388; Smithsonian). The Louisiana Purchase proved to be the most popular moment of Jefferson's presidency.

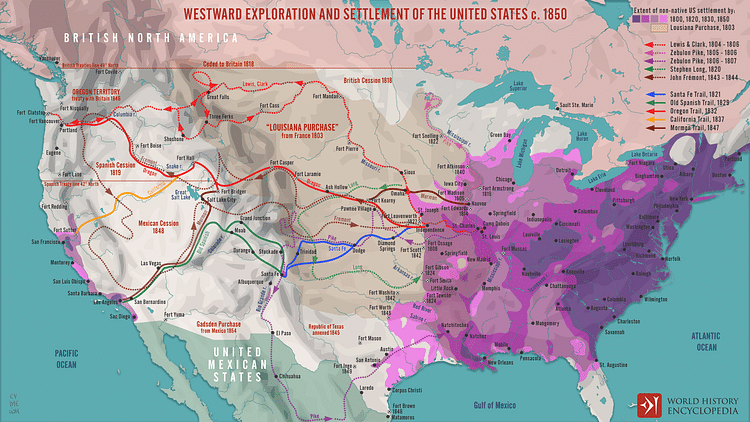

The Louisiana Territory was a vast chunk of land, stretching from the Mississippi River in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west. Most of these lands remained unexplored, leading Jefferson to commission several expeditions to explore and chart the territory, the most famous being the Lewis and Clark Expedition (14 May 1804 to 23 September 1806). But the exact boundaries of the Louisiana Territory remained hazy, leading to years of negotiations with Spain and Great Britain. The Americans believed that West Florida had been included in the Louisiana Purchase, an assertion that Spain denied; this dispute was ultimately settled in 1819 when the US purchased Florida from Spain. Additionally, the US and Britain agreed to fix the northern boundary of the territory in 1818 at the modern US-Canada border.

For a while, Jefferson was concerned that the Louisiana Purchase was unconstitutional and considered amending the US Constitution to allow for it. This proved to be unnecessary, however, as the US Senate ratified the purchase treaty on 20 October 1803 by a vote of 24 to 7. Spain felt betrayed by the purchase, having previously been promised that France would not sell Louisiana to a third party. But there was nothing Spain could do except transfer Louisiana to France on 30 November as agreed, before France, in turn, transferred the territory to the US on 20 December. On that day, the French tricolor was lowered in the main square of New Orleans and the American flag was raised. The modern-day states ultimately carved out of the Louisiana Territory include Louisiana, Missouri, Arkansas, Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Oklahoma, as well as parts of Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and Minnesota.