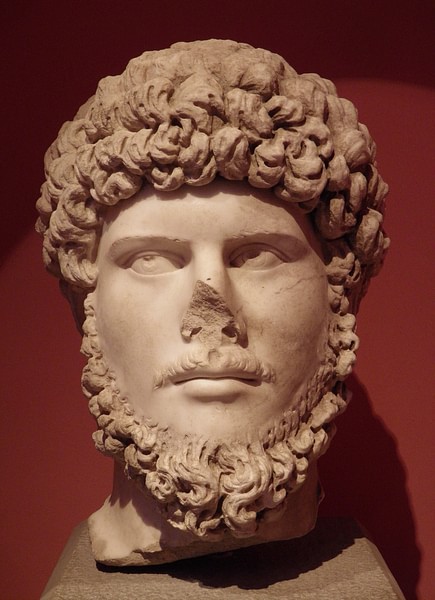

Lucius Verus was Roman emperor from 161 to 169 CE. Lucius Verus was Marcus Aurelius' adopted brother and co-emperor, a man whose time on the throne is overshadowed by the reign of the last of the Five Good Emperors. In the final years of the Pax Romana, a period of almost two centuries of relative peace and stability following the rule of Augustus, a young Stoic philosopher, Marcus Aurelius, came to the throne in 161 CE, and for the first time in the empire's short history he chose to have someone rule at his side; his adopted brother Lucius Verus.

Adoption & marriage

The future emperor Lucius Ceionius Commodus was born in 130 CE and raised in Rome, the eldest son of the one-time consul Lucius Aelius Caesar. Since the childless Emperor Hadrian (117 CE – 138 CE) was without either a successor or heir, he chose, against the wishes of many, the 35-year-old Aelius to be his adopted son in 136 CE. Aelius was immediately dispatched to the Roman province of Pannonia (located to the north along the Danube) to serve as governor. Unfortunately, however, Aelius died of tuberculosis suddenly in January of 138 CE. In his place, the emperor opted to adopt his second choice for an heir, Aurelius Antoninus Pius, also known as Antoninus the Dutiful. Although Hadrian wanted the much younger Marcus Aurelius to succeed him, he realized Marcus was far too young and instead chose the highly respected but elderly Antoninus – many thought him to be harmless – until the young Marcus matured. To ensure both an orderly line of succession and as a condition of his adoption, Antoninus subsequently adopted both his nephew Marcus and Aelius's son Lucius. The relatively young Lucius would henceforth become known as Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus; he would later drop Commodus and add Verus after ascending to the throne.

Like his brother, Lucius was not new to the Roman political scene, having served as a quaestor in 153 CE and consul in both 154 and 161 CE – the latter was with Marcus. So, in March of 161 CE, after a 23-year reign, the death of Emperor Antoninus Pius brought Marcus Aurelius to the imperial throne, assuming the titles of Augustus and Pontifex Maximus. Out of respect for his adopted father's wishes, he immediately appealed to the Roman Senate to name his 'brother' Lucius to rule at his side, bestowing upon him tribunician powers as well as the titles of both Caesar and Augustus. Under Antoninus, trade and commerce had flourished, and his strict control of finances allowed for a state surplus by the time of his death. However, while the rule of Antoninus Pius had seen years of peace and economic stability, the reign of Marcus and Lucius experienced almost constant warfare in the north and east as well as a devastating plague that swept through the entire empire.

Aside from their adoption, marriage secured both men to the throne. Marcus wisely divorced his first wife and married Faustina the Younger, the daughter of Antoninus, while Lucius married Marcus' daughter Annia Aurelius Galeria Lucilla at Ephesus in 164 CE. In his Roman History, the historian Cassius Dio wrote,

Marcus Antoninus, the philosopher… was frail in body himself and devoted the greater part of his time to letters. … Lucius, on the other hand, was a vigorous man of younger years and better suited for military enterprises, Therefore, Marcus made him his son-in-law by marrying him to his daughter Lucilla and sent him to conduct the war against the Parthians. (Vol. IX, 3)

After Lucius' abrupt death in 169 CE, she would marry the military commander Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus. Unfortunately, she became involved in a plot against her brother, the Emperor Commodus (Marcus' son), and was exiled and later executed.

Parthian War

Almost immediately upon assuming the throne, trouble – a dilemma their adopted father had been able to avoid – was brewing in the east. Lacking the calm nature and diplomatic skill of Antoninus Pius, the two new emperors became embroiled in the Parthian War. The war began over the control of Armenia, a territory that Emperor Trajan had named a Roman protectorate or client-state. The Parthian king Vologases IV (148-192 CE) expelled the Roman governor and placed a man named Pacorus on the throne. The Parthians then quickly defeated the Roman governors of Cappadocia and Syria. Although it would take him nine months to get there, Lucius was sent eastward in command of the Roman forces. The costly delay was blamed by some on illness while others pointed to his 'pleasure-loving' temperament. The authors of the Historia Augusta wrote:

… while legions were being slaughtered, while Syria meditated revolt, and the East was being devastated, Verus was hunting in Apulia, travelling about through Athens and Corinth accompanied by orchestras and singers. (207)

When he finally arrived, Lucius spent much of his time at a resort outside Antioch. Thankfully, the Roman generals were more than capable, eventually opposing and defeating the Parthians. The commander Statius Priscus invaded Armenia, capturing and destroying the capital city of Artaxata while the new governor of Syria, Gaius Avidius Cassius, and commander Publius Verus moved further eastward into Mesopotamia, conquering the cities of Odessa, Nisibis, and Nicephorium. The war finally ended in 166 CE with the capture and sack of the cities of Seleucia and Ctesiphon; in Ctesiphon, the royal palace of the Parthian king was completely destroyed. Afterwards, Mesopotamia would remain a Roman client-state.

Despite his limited involvement in the war, Lucius was hailed with a triumph (the first since Trajan) upon his return to Rome in October 166 CE, a triumph he would share with his brother. In addition, he and his brother (who had no involvement in the war) were given the additional titles of Armeniacus, Parthicus, and Medicus. Both brothers were also hailed as Pater Patriae (father of the country). The war against the Parthians would serve as a prelude for their move against the Germanic tribes to the north.

The Antonine Plague

Problems northward along the Danube River drew the attention of Marcus and Lucius after the offensive in the east ended; preparations were made to move towards Germania in 167 CE. Unfortunately, something unforeseen had arrived in Rome with the returning army from Mesopotamia, a plague known forever in history as the Antonine Plague. The plague would spread throughout Asia Minor, Greece, and into Italy, eventually making its way northward to the Rhine. Many years later, it would be blamed for a partial weakening of the empire. The plague, together with a shortage of food, delayed the brothers, so when they finally arrived to do battle, the invaders had withdrawn. The plague would claim ten percent (some claim 30 percent) of the empire's population. The Roman physician Galen (129-199 CE) described its symptoms as diarrhea, high fever, and pustules on the skin. It was later believed to have been smallpox.

While Marcus was demanding a drive across the Alps, his brother was pushing for a return to Rome. They took up winter quarters at Aquileia. As the plague spread among the army, they decided it was best to return to Rome and set out for the city in 169 CE; however, at Altinum, Lucius became ill, suffered a stroke and died as a supposed victim of the plague. His body was returned to Rome where he was buried in Hadrian's mausoleum alongside Antoninus Pius, later to be deified. To protect the empire from the plague Marcus, always the Stoic philosopher, appealed to the Roman god Apollo at his oracle at Claros in eastern Asia Minor to dispel the demons.

Legacy

Marcus would rule until 180 CE when his son Commodus took the throne. Marcus' death brought an end to the Roman peace, for he was the last of what history calls the Five Good Emperors – Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius. Those emperors who followed for the next century would witness a time of both chaos and decline. Commodus, the first of these inept emperors, was not only unscrupulous and corrupt but also power-hungry, seeing himself as the reincarnation of the Greek god Heracles (Hercules). Although Commodus considered his reign a Roman golden age, his lack of concern for political matters together with his life of leisure and extreme paranoia brought about what others might consider a reign of terror. He was eventually poisoned (192 CE) and when that failed choked to death.

The reign of Lucius Verus became lost within his brother's time on the throne. While he participated, albeit in name only, in the Parthian conflict, his eight years of rule brought him little glory. His was the adopted son of an adopted son, the son of one of the better emperors, Antoninus Pius. While his name is almost completely lost to history, having demonstrated little in military acumen, he is best known for simply falling victim to the plague.