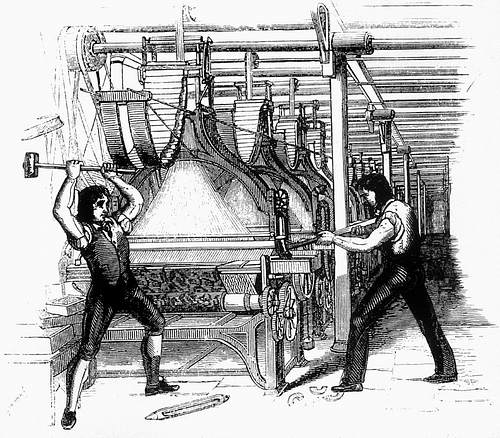

The Luddites, named after their legendary leader Ned Ludd, were workers who protested at the mechanization of the textile industry during the Industrial Revolution. From 1811 to 1816, the violent strategy of the Luddites was to smash the machines they thought had taken or threatened their jobs, to burn down factories, and to attack the private property of factory owners.

The Mechanization of Industry

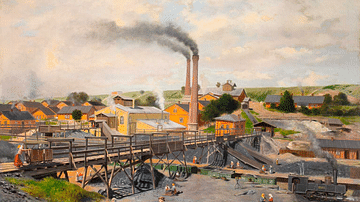

The textile industry was traditionally a cottage industry (aka the 'domestic system') where spinners and weavers worked in their own homes or in small workshops. They used simple, hand-powered machines such as the spinning wheel and handloom. Inventors and entrepreneurs were keen to increase production rates and lower the costs of textiles. This was achieved by creating machines that used water wheels or steam power that could do much more work than one individual could using more traditional methods. Machines like the spinning jenny (invented by James Hargreaves in 1764), the water frame (by Richard Arkwright in 1769), the spinning mule (by Samuel Compton in 1779), and the power loom (by Edmund Cartwright in 1785) greatly speeded up both the spinning of yarn and the weaving of cloth. The differences compared to hand-operated machines were enormous. A single spinning mule machine could have 1,320 spindles compared to the single spindle on a wooden spinning wheel. A factory or mill might have more than 60 such spinning machines while there were single factories using 1,000 of Arkwright's weaving water frames.

While there were still many spinners and handweavers working as they always had done, the future was obviously with machines. But even worse for skilled workers who made textiles by hand, the factory machines did not need any particular skill to operate. Many mill owners now employed women and children because of this and because they were cheaper than men. In addition, those men skilled at textile production that were employed in the new mills could not command the same wages as they had previously. The lower costs of textiles that factories were able to achieve meant that market prices plummeted and hand weavers could only earn in a week what they had previously done in a day of work. It was not just a case of losing money and jobs but, as textile workers were typically concentrated in particular areas, whole communities were thrown into turmoil. Some men decided to fight back, and these were the Luddites.

Smashing Machines, Arson, & Violence

Traditional textile workers were not slow to see the threat of machines to their livelihood. Robert Grimshaw intended to install 500 Arkwright water frames in his new factory at Knott Mill in Manchester, but it was burnt to the ground in 1790 after only 30 of the machines had been installed. Arkwright deliberately built his new model factory at Cromford on the River Derwent in Derbyshire, far away from any textile workers for his own safety and that of his machines. He later fortified the factory and even added cannons to its formidable defences. This phenomenon of attacking new machine inventions was not peculiar to Britain. France had experienced a wave of machine smashing by working-class militants from 1789 to 1791. The same tactics would be used by 5,000 German handloom weavers in Silesia in 1844.

In the great manufacturing towns and cities of Yorkshire, Lancashire, Leicestershire, Derbyshire, and Nottinghamshire between 1811 and 1816, a new, more violent protest group emerged, the Luddites. They were named after their mythical leader Ned Luddham, aka Ned Ludd, King Ludd, and General Ned Ludd, "a supposed Leicester stockinger's apprentice who responded to his master's reprimand by taking a hammer to a stocking frame" (Horn, 2005, p146). This was meant to have happened in 1779, and the Ned Ludd name was kept alive in popular memory by using it as a label for someone who protested against authority and technological change.

The Luddite protestors were not really unified as a group but, rather, were working-class people in different areas with the same preoccupations and the same intent to do something about them. The first Luddite outbreak came in Nottinghamshire, with similar copycat attacks then being carried out elsewhere. The Luddites' strategy was often no-holds-barred, and they frequently threatened the factory owners personally. One such threatening letter, sent to a factory owner in Huddersfield, Yorkshire, read:

Information has been given that you are the holder of those detestable shearing frames. I shall send one of my lieutenants with at least 300 men to destroy them and burn your building to ashes ...

(Hepplewhite, 29)

The letter was signed by King Ludd. The Luddites were often good on their threats. They broke into factories, smashing the hated textile machines with hammers.

Revolutionaries or Reactionaries?

Some historians have seen the Luddites as part of a wider revolutionary movement that sought to topple the capitalist establishment. In this period, there certainly were food riots and strikes because of the poor economic conditions for the working classes in general. Sometimes protestors of various motivations did combine with bread rioters, moving on to a nearby factory, for example. As far as E. P. Thomson is concerned: "Luddism was a quasi-insurrectionary movement which continually trembled on the edge of ulterior revolutionary objectives" (Hewitt, 50). Other historians maintain that the Luddites were in no way linked to other protest movements. M. Thomas and P. Holt note the Luddite movement "was more a spasm in the death throes of declining trades than the birth pangs of revolution" (ibid).

The Luddites were labelled as revolutionaries by some of those in government, but it is well to remember that trade unions were officially banned between 1799 and 1824 in Britain. Textile workers, whether they worked in their own homes or in factories, had no collective representation for often valid grievances, such as wage reductions and poor working conditions. It is likely, then, that some of the Luddites felt they had no other option but to make these grievances heard by attacking property. Some Luddites may have wished to overthrow the established system of employment entirely, but others would have settled, no doubt, for a more balanced system which was not so biased towards owners and capital.

The Government Fights Back

The Establishment fought back against the Luddites. In February 1812, the British Parliament passed a bill that meant anyone found guilty of breaking textile machines faced the death penalty. Spies, working for local magistrates and handsomely paid, were sent out to find out who was organising and carrying out the attacks on private property. Handsome cash rewards – up to £200 ($14,000 today) in some cases – were offered for information on or for the capture of Luddites. The army was called in to protect specific factories and their owners and to disperse large protest gatherings of workers. Sometimes the army fired at the protestors, which ended in a number being killed or wounded. 12,000 troops ensured order was maintained in this way. There were even militias formed by the propertied class to protect their own interests in the areas neglected by the government. Those protestors who were caught faced penalties ranging from fines to hanging or deportation to Australia. In two cases in York in 1812 and 1813, 17 Luddites were hanged, one group for murdering a factory owner and another for attacking a mill.

It is important to note that the Luddites were a minority within the profession of handweavers who, by the very nature of their work in isolated cottages, could not gather in groups and so they often stoically put up with the decline in their industry. A report compiled by a government committee, far from condemning handweavers as violent protestors, praised their patience with the momentous upheaval caused by mechanization:

The sufferings of that large and valuable body have for years continued to an extent and intensity scarcely to be credited or conceived and have been borne with a degree of patience unexampled.

(Hewitt, 51)

By 1816, the Luddite movement was losing its steam as the general economic situation in Britain improved after a period of recession. However, there were sporadic machine-breaking episodes into the 1830s, and there were numerous cases of agricultural workers taking up the idea and smashing threshing machines, the main threat to their own livelihood. In the end, though, the absence of any central coordination was another reason the movement failed to gain any real momentum. A third reason was the government's enthusiasm for repressing the movement and dealing out harsh punishments for those found guilty of Luddism. A fourth reason the protests and destruction ended was that factories created many more jobs than the traditional textile industry had ever done, even if these were less skilled and less well-paid. Agricultural workers, in particular, flocked to the bigger cities eager to find regular work in the mechanized factories, and the Luddites got little support for trying to preserve a way of life that many recognised had already had its day. Indeed, the term 'Luddite' came to be widely used henceforth for someone who was incapable of understanding that change and new technologies are, then as now, a constant part of working life.

Aftermath

Violence proved an unsuccessful strategy for the Luddites, but there were others with an alternative approach. Some textile workers fought back against the rise of the machines using their brains instead of muscles, as explained by the historians Sally and David Dugan:

A group of women weavers in Yorkshire, for instance, managed to maintain their independence by setting up a cooperative woollen mill. They carried on weaving at home, only bringing their cloth into the mill to be finished. In Coventry, some silk weavers invented a half-way house to the factory system. Their cottages were lined up along a court, with a steam engine at one end, and an engine shaft running through the houses. Workers paid rent to hook up to the power source, and this helped them to maintain a semi-independent status for a while. (65)

The Luddites and those who wanted to keep a modified version of the old cottage industry, were, though, fighting a losing battle. Evermore versatile machines were on the horizon, and these were capable of working more efficiently than before and working around the clock. In 1822, Richard Roberts (1789-1864) invented a new iron loom, and in 1825, he created his self-acting mule that had the spindles turn at varying speeds depending on how full they were. Essentially, workers now just had to make sure the machines were kept clean, fix any blockages, and remove the spindles when full. By 1835, around 75% of cotton mills were using steam power, and there were well over 50,000 power looms being used in Britain. In short, the British "cotton mill of 1836 was so efficient that it could out-compete hand spinning anywhere in the world" (Allen, 187).