The Maasai (or Masai) people are an East African tribe who today principally occupy the territory of southern Kenya and northern Tanzania, and who speak the language of the same name. The Nilo-Saharan Maasai migrated southwards to that region in the 16/17th century CE, and they thrived thanks to their skills at animal husbandry, especially the herding of cattle. Maasai warriors are particularly famous for their height, stamina, and striking red hair and their success in warfare brought them domination of the Rift Valley grasslands. The Maasai Mara game reserve in southern Kenya is named in honour of the tribe which still lives there.

The Maasai Tribe Migration

The Maasai were originally a Nilo-Saharan people centred around the area of what is today Sudan. They then migrated southwards, along with other tribes such as the Tutsi, searching for better grazing and agricultural lands, a quest which eventually took them into central East Africa around 1750 CE. They passed through the highlands of Kenya and past Lake Turkana, finally settling on the savannah grass plains of what is today southern Kenya and northern Tanzania. The Nilotic-Kushite origins of the Maasai are evident in their physical characteristics and the many instances of words borrowed from Kushite or Eastern Nilotic languages present in the Maasai or maa language.

The Maasai were influenced in some aspects of their culture by Nilotic peoples settled in the Highlands of Kenya who had migrated there earlier. Consequently, such cultural practises as circumcision and a fish taboo were adopted, too, by the Maasai. The arrival of the Maasai in the region in the late-16th and early-17th century CE also saw the decline in the dominance of local tribes.

The Maasai peoples adapted extremely well to their new environment, as the UNESCO General History of Africa Vol. II puts it: "In these fine pastures, in fact, the central Maasai sections succeeded…in pursuing the pastoral ethic to its ultimate extreme" (323). The irregular rainfall of the inland zones of Kenya and Tanzania had meant that the Maasai were obliged to focus on stock-raising, especially of cattle, and abandon the cultivation of grain in some areas. Other animals herded on a much smaller scale included goats, sheep and poultry. Livestock provided milk, blood to drink, dung for fuel, material for weapons, tools and clothing, and, occasionally, meat.

The Maasai continued to expand their domain, which is sometimes called Maasailand and is approximately located in the area between Lake Victoria in the East and Mount Kilimanjaro in the west, by sending out younger generations of families to settle new pastures with a certain quantity of the home community's livestock. This process continued through the 17th and 18th century CE as the tribe looked for 'empty lands' where there was a low existing population. As East Africa began to fill up over time with competing tribes and populations increased in density, so the Maasai were obliged to fight for their right to raise animals in a particular area, this was especially so in the 19th century CE.

The Maasai Oral Tradition

The Maasai developed an oral tradition which reinforced their own view that they were the only pure pastoralists in East Africa. The stories essentially identify the Maasai as superior in all ways to other tribes, especially hunters (Dorobo) and agriculturalists who had to perform such undignified tasks as digging the soil. One such tale tells the consequences of the Dorobo people ignoring a message from God to await his gift of cattle. They do not turn up as instructed and consequently lose out to the Maasai. The story is quoted here from P. Curtin's African History:

God let down a bark-rope…from the sky and began to let cattle down, until there were so many that they intermingled with those of the Dorobo. Then the Dorobo came, and when he could no longer recognize his cattle among those of the Maasai, he was angry and shot away the bark-rope with an arrow…God caused the cattle to stop descending and he moved up into the sky, and was never seen on the ground again. Thus all cattle which Maasai now own were first given to them by God. (113)

Other oral traditions perpetuate the belief that the Maasai were born to be cattle herders, including literally that the first male progenitor of the tribe was given a herding stick for this purpose. Further, it was thought that this specialisation should not be compromised by taking up other activities which other peoples pursue such as hunting and farming. It is important perhaps to note, though, that pure pastoralism amongst the Maasai probably only arrived quite recently (c. 1800 CE) and a minority of Maasai groups and some Maasai-speaking peoples did subsist almost exclusively by farming. It seems clear then that the oral traditions favouring pure pastoralism were really only a device by those rich elites with many cattle to justify and perpetuate their position at the top of Maasai society - they never had a need to resort to farming and so they had the right to rule.

Society & Property

Maasai status in their society was dictated and measured by how many cattle a male owned. Livestock was an indicator of prosperity and animals were commonly offered as part of a bride price, but the Maasai did sometimes lend their cattle to kinsmen in difficulties, too. In a certain sense, cattle held communities together by providing a common and mutually beneficial bond of ownership. Animals were herded by specific members of kin groups, but the whole belonged to the wider social unit irrespective of their actual geographical spread. The emphasis on cattle and the large number required to support a family did have unfortunate repercussions for the poorer members of Maasai society. In times of drought when milk was in short supply or animals even died, those with only a small herd were forced to farm or hunt for themselves, which as we have seen above, was regarded as the ultimate failure.

All Maasai individuals belonged to a family, clan, and district group. Representatives of these groups formed councils of male elders - seniority in age was an important criterion for the Maasai elite - which met regularly to discuss and decide matters important to the Maasai as a whole and establish the rights and mutual obligations of each of these three levels of society. Elite groups typically ended up controlling the best grazing land and the vital watering places. Youths were permitted into adulthood through initiation ceremonies which involved circumcision (for both sexes).

Prosperous groups of Maasai were able to permit some individuals to pursue other activities such as basketry, textile work, religion, and art. Another task could be housebuilding, traditionally regarded as a woman's responsibility along with the household chores and childcare, while men tended the animals. Trade with other tribes permitted the acquisition of such necessities as grain, vegetables, and other foodstuffs produced by agriculturalist tribes (notably the Kikuyu), salt, iron, weapons, tools, and luxury goods such as well-made pottery and decorative items for the body and home. Interestingly, trade was the responsibility of Maasai women. The Maasai paid for these goods in the form of cattle, milk, skins, and leather. Another area of exchange was expertise, with the pastoralists performing minor surgeries and tooth extractions in return for the agriculturalist's knowledge of medicines.

Maasai Warriors

The Maasai may have been expert pastoralists but they were also famed and feared as warriors. Indeed, warfare was often necessary because the Maasai required large swathes of territory for their animals to graze, a fact which often brought them into conflict with neighbouring peoples. Between 1500 and 1800 CE, societies in East Africa were still very much taking shape with a very large number of quite separate communities. The Miji-Kenda, like the Maasai, sought to expand their territory and so the two inevitably clashed. Another rival group was the Padhola, particularly in the Tororo area, and a third was the various hunter peoples in East Africa. Competition for land and resources only increased in times of climate extremes such as droughts.

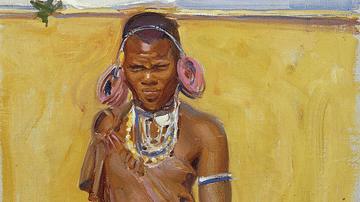

The Maasai warriors (moran) were controlled by ritual leaders (laibons). Warriors lived together in separated clusters of dwellings, ate in each other's presence, shared property, and always travelled together in small groups. They trained by throwing their spears at targets, improved stamina and physique by wrestling and fighting mock-battles, and displayed courage by hunting lions. Besides their distinctive red robes and short cape, warriors grew their hair long and caked it in a mixture of mud, cow fat and ochre. They also wore a beaded belt with a short knife and sometimes an impressive ostrich-feather headdress.

Warriors performed war dances, which included distinctive jumping up and down on the spot and other physical movements required in battle, and then set out armed with their very long spears to defeat their enemies. The Maasai were highly successful in warfare throughout the 18th century CE, although this is perhaps not surprising considering their opposition was composed of much less-militarised societies. The Cambridge History of Africa gives the following concise record of their success:

[The Maasai] established a virtual monopoly of the Rift Valley grasslands all the way from the Uasin Gishu plateau in north-western Kenya to the Maasai steppe in north-central Tanzania, a distance of approximately 970 kilometres…the Maasai predominance drove back and fundamentally changed the way of life of the older established Southern Paranilotic group. (654)

Later History

Despite their spectacular success in the previous century, the Maasai were in decline by the 19th century CE as the age-old battle between pastoralists and agriculturalists began to swing in favour of the latter. This is because the settled agriculturalists were now creating more sophisticated and centralised forms of government, which increased their prosperity. The Maasai, with few permanent roots and living in scattered communities, suffered from a lack of political and military organization compared to other, more sedentary groups once they turned their attention to warfare. The Maasai position was further weakened by the hunting of their animals by such peoples and losses to disease epidemics. From around 1850 CE, there were, too, damaging civil wars between rival Maasai groups which often drove away valuable warriors who then became mercenaries for neighbouring tribes such as the Nandi.

The Maasai did survive the European colonial era in Africa, the eastern portion of the continent being dominated by the British, Italians, and Germans. Their independence throughout this turbulent period of African history was largely thanks to their habitation of desert areas as they were driven off the grasslands by expanding agriculture, which was promoted by the Europeans. The British colony of Kenya gained its independence in 1963 CE, and the Maasai have staunchly resisted all government initiatives to 'modernise' them ever since.

The Maasai Mara

The Maasai Mara is a large game reserve in southern Kenya which was named after the Maasai people in recognition of their long-standing occupation of the territory which it covers. The reserve, located in the Rift Valley of East Africa, was established in 1961 CE. It is one of the most famous game parks in Africa and is celebrated for its diverse wildlife which includes lions, elephants, and leopards. The reserve also sees the large annual movement of wildlife both to and from the Serengeti to the south known as the Great Migration. The naming of the park was not just an empty gesture to the Maasai as they are still today permitted to graze their livestock in parts of the reserve.