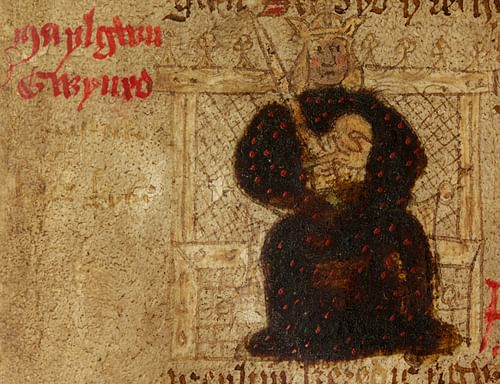

Maglocunus, known as Maelgwn Gwynedd in Welsh (d. c. 547), was a 6th-century monarch based in Gwynedd, in north-western Wales. Maglocunus' name means "princely hound", and he expanded his influence to become one of the pre-eminent rulers of Britain in the 6th century.

Unusually for an early medieval British king, we have a contemporary account of his reign, in the form of Gildas' De Excidio Britanniae (On the Ruin of Britain). Gildas (c. 500-570) presents him as a violent and tyrannical ruler; later writers, however, generally portray him in a more neutral or positive light. Maglocunus is the version of his name given in Gildas, and appears to come from the Common Brythonic *Maglo-kunos or "princely hound". This evolved to Mailcun in Old Welsh, and Maelgwn in Middle and Modern Welsh; all three versions of the name are given to him in the historical and legendary sources.

Background to Maglocunus' Reign

After the withdrawal of the Roman army from Roman Britain and the collapse of Roman authority during the 5th century, the island had reverted to the control of native British leaders ruling over small kingdoms based on the old Roman government districts, or civitates as they were called in Latin. These little realms were vulnerable to raids and invasions, particularly from the Irish to the west and the Picts to the north. In an attempt to boost their defences, the Britons hired Saxon mercenaries whom they paid with land and food – a strategy copied from the Western Roman Empire.

As often happened, this strategy ended in disaster, as a dispute over pay caused the Saxons to rebel against their erstwhile employers c. 441 CE. Almost uniquely among the inhabitants of the former Roman Empire, however, the Britons managed to organise against the invaders before they were completely overrun. There followed about half a century of warfare between the Britons and the Saxons, with many victories on either side. Although the Britons could not drive the Saxons out of Britain altogether, they controlled most of the island, with the Saxons driven back to the eastern parts of the island. A period of relative peace ensued, lasting until c. 577, and it was during this time that Maglocunus' career was situated.

Maglocunus' Ancestry

Maglocunus' family had been prominent in Britain since Roman times. His ancestor Paternus (Welsh Padarn) was nicknamed Beisrudd or "Red-Cloak"; scarlet cloaks were a mark of high rank in the Roman army, and it, therefore, seems likely that Paternus held some kind of senior military command. Later tradition places his descendants in the Gododdin region, roughly coterminous with present-day Lothian. One of Paternus' descendants, Cunedda by name, moved to north Wales and drove out the Irish who had occupied the region. The 9th-century historian Nennius dates this to 146 years before Maglocunus' reign, that is, sometime in the late 4th century. It is possible that Cunedda was acting on imperial authority to shore up the defences of a vulnerable part of Roman Britain.

Gildas' Record

Most of our information about Maglocunus comes from Gildas' De Excidio Britanniae. Gildas was a monk who believed that British immorality and wickedness would bring divine judgement and disaster upon the country. He wrote De Excidio in order to highlight the sinfulness of Britain's secular and religious rulers and urge them to repentance. As part of this, he condemns five British kings by name: Constantine of Dumnonia, Aurelius Caninus, Vortiporius, Cuneglassus, and – "last in my writing, first in wickedness" (Gildas, De Excidio Britanniae, 33) – Maglocunus.

Gildas tells us that Maglocunus was a notably powerful man, both politically and physically: "the King of all kings… made thee superior to almost all the kings of Britain, both in kingdom and in the form of thy stature" (Gildas, De Excidio Britanniae, 33). This power was gained by violent means: whilst still a young man, Maglocunus had overthrown his own uncle and seized control of his kingdom, and subsequently went on to depose and kill "many of the tyrants mentioned previously" (Gildas, De Excidio Britanniae, 33) – either the four others specifically named, or else the British tyrants in general, whom Gildas has earlier castigated en masse.

These violent actions seem to have troubled Maglocunus' conscience, however, as some time after seizing power he abdicated and became a monk, causing "much joy and pleasantness, both to heaven and to earth" (Gildas, De Excidio Britanniae, 34). It is possible that he met Gildas himself during this period: Gildas knows about the tyrant's outstanding physical appearance, perhaps indicating a personal acquaintance, and a friendship and subsequent estrangement might explain some of the vitriol which Gildas shows towards him.

Maglocunus did not long remain in his monastery. He soon returned to his old ways, "like a sick dog to its fearful vomit" (Gildas, De Excidio Britanniae, 34), and seems to have taken control of his kingdom once again. He got married shortly afterwards, before tiring of his new bride and murdering his own nephew in order to marry this man's wife instead.

Other Sources

Gildas, writing whilst Maglocunus was still alive, naturally gives no details regarding his death. The 10th-century Annales Cambriae (Annals of Wales), however, report that "Mailcun king of Gwynedd" passed away in a "great plague" in the year 547. This was probably Justinian's plague (541-542 CE), which struck the Byzantine Empire and subsequently spread throughout Europe and the Middle East, claiming the lives of millions of people.

Maglocunus is also mentioned, under the name "Mailcunus", in Nennius' 9th-century Historia Brittonum (History of the Britons). A Welsh monk, Nennius tells us that Maglocunus "reigned as great king among the Britons, that is in the Gwynedd region," at the same time as "Talhaern Tataguen was famous for his poetry, and Neirin, Taliesin, Bluchbard, and Cian, who is called Guenith Guaut, were also famous in British poetry" (Nennius, Historia Brittonum, 62). We know from Gildas that Maglocunus was fond of listening to praise poems composed in his own honour, and it is possible some or all of the poets mentioned by Nennius found patronage in Maglocunus' court.

Later books of ecclesiastical records, such as the 12th-century Book of Llandaff, mention Maglocunus as a benefactor of the Church. His donations are recorded across Wales, indicating that his control spread beyond the borders of Gwynedd. He is also commemorated in a rare surviving example of Dark Age British epigraphy: a stone in Nevern, Pembrokeshire, bears an inscription in Latin and Ogham reading, "[The monument] of Maglocunus son of Clutorus".

Reliability of the Sources

Although we have more sources for Maglocunus' life than for almost any other 6th-century ruler, we must nevertheless bear in mind their limitations. Gildas, as a contemporary and possible personal acquaintance of the monarch, should have the most reliable information, although the moral purpose of his De Excidio Britanniae causes him to emphasise what he sees as the more negative aspects of Maglocunus' reign. We do not know how widely Gildas' negative assessment was shared among contemporaries.

Nennius, writing several centuries after Maglocunus' death, would have relied on oral and written records of his life; since these records have not survived, we are unable to check their accuracy. Nennius shows no knowledge of Gildas' account – details such as Maglocunus overthrowing his uncle, joining a monastery, and marrying his nephew's wife, are all absent from the Historia – so it seems that he does at least offer independent confirmation of Maglocunus' status as a powerful monarch. The association of Maglocunus with Gwynedd has been questioned on the grounds that 6th-century Gwynedd was something of a backwater, whereas Maglocunus himself was evidently a powerful figure. It is possible to reconcile these two data points, however: Gildas reports that Maglocunus overthrew many other tyrants, so it is possible that he began his career as ruler of Gwynedd, before conquering nearby kingdoms and thereby becoming one of the leading monarchs of Britain.

The Annales Cambriae similarly appear to be independent of the Historia Brittonum. The original manuscript does not actually give dates for the events it records: instead, it is marked as a sequence of years, each one designated by the word "an." (an abbreviation of the Latin annum, "year"). To calculate the dates of events, we have to start from an event whose date we do know and then count forwards or backwards. Unfortunately, these events do not all have the right number of years listed between them. Depending on which event we take as our starting point, therefore, the death of Maglocunus could be placed as early as 537 or as late as 550.

Maglocunus' Legacy

As befits such a powerful figure, Maglocunus continued to be remembered in Welsh legend long after his death. He is mentioned in the medieval Welsh Triads: his cow Brech ("Speckled") was apparently one of the Three Principal Cows of the Island of Britain, whatever that might mean. Maglocunus also plays an important role as the antagonist of the late medieval Ystoria Taliesin or Tale of Taliesin. In this, he is portrayed as a wealthy and powerful monarch, but also somewhat arrogant: he imprisons Taliesin's friend Elphin when the latter claims to have a more virtuous wife and more skilful bard than the king until Taliesin releases him using magic. Taliesin and Maglocunus do seem to have been contemporaries, judging by Nennius' account, but the Ystoria Taliesin, like the Arthurian romances being circulated during this same period, is fundamentally a work of fiction, drawing on historical traditions about early medieval Britain but by no means bound by them.

Outside Wales, Maglocunus was best known for his appearance in Geoffrey of Monmouth's pseudohistorical Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain). Geoffrey's account of Maglocunus (or "Malgo", as Geoffrey calls him) is heavily based on Gildas, although Geoffrey puts a much more favourable spin on the monarch's actions.

Echoing Gildas, Maglocunus is described as "the most handsome of almost all the leaders of Britain". We are also told that he "strove hard to do away with those who ruled the people harshly" (Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum Britanniae, 11.7), apparently based on Gildas' report that he had "driven many of the tyrants mentioned previously, as well from life as from kingdom" (Gildas, De Excidio Britanniae, 33). The only vice which Geoffrey attributes to Maglocunus is that of sodomy, a possibly overliteral interpretation of Gildas' description of him "[wallowing] in such an old pool of black crimes, as if sodden with the wine that is pressed from the vine of Sodom" (Gildas, De Excidio Britanniae, 33).

Unlike Gildas, for whom Maglocunus is simply one, albeit powerful, British monarch, Geoffrey claims that Maglocunus "became ruler of the entire island" (Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum Britanniae, 11.7); this almost certainly comes from Geoffrey's anachronistic conception of "Britain" (i.e. England) as having always been united, rather than from any genuine early medieval tradition. Geoffrey even claims that Maglocunus' authority extended beyond Britain itself to encompass the six neighbouring "islands" of Ireland, Iceland, Gotland, the Orkneys, Norway, and Denmark. His source for this claim is unclear, although we can be certain that no real 6th-century polity ruled all these lands.

Maglocunus was remembered by his descendants, the kings of Gwynedd, as an important early member of their dynasty. Although Gwynedd's control over the surrounding kingdoms does not seem to have outlived Maglocunus himself, his descendants ruled in Gwynedd for over seven centuries after his death, making their family perhaps the oldest royal house of medieval Europe by the time of their demise. Gwynedd once again became the most powerful Welsh kingdom during the reign of Rhodri the Great (844-78) and was the last of all the Welsh territories to fall to the invading English in 1282. Hence for a period of some 400 years, Maglocunus' descendants played a leading role in Welsh affairs and in maintaining their country's independence against the descendants of those same Anglo-Saxons, whom his ancestors had fought back in the 5th century.