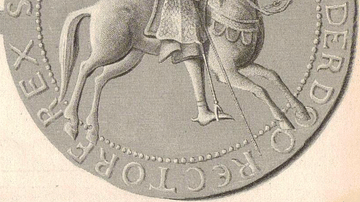

Malcolm III of Scotland (aka Máel Coluim mac Donnchada) reigned as king from 1058 to 1093 CE. He took the throne after his young predecessor Lulach (r. 1057-1058 CE), the stepson of Macbeth, king of Scotland (r. 1040-1057 CE), was killed in an ambush. Malcolm thus restored the ruling house of Dunkeld, founded by his father Duncan I of Scotland (r. 1034-1040 CE). He had been helped in removing Macbeth and Lulach from the throne by the English king Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066 CE) who hoped to make Malcolm his puppet across the border. The Norman Conquest of England in 1066 CE then upturned English-Scottish relations and Malcolm married Margaret, sister of a Saxon claimant to the English throne now occupied by William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087 CE). Repeated raids in both directions continued to sour relations, and Malcolm was killed in one such expedition in Northumbria in 1093 CE. Malcolm was succeeded by his brother, Donald III of Scotland (r. 1093-1097 CE). Remarkably, four of Malcolm's sons would rule as kings of Scotland while his daughter became the Queen of England.

Macbeth & the Dunkelds

Duncan I of Scotland (aka Donnchad ua Maíl Choluim) was born c. 1010 CE and he had inherited the throne via his mother Bethoc, who was the daughter of the previous king, Malcolm II of Scotland (r. c. 1005-1034 CE), the last of the McAlpin kings. Duncan, whose father was Crinán, lay abbot of Dunkeld, thus founded the House of Dunkeld, which would rule Scotland until 1286 CE. Duncan proved to be a less than capable ruler, and his failure to expand his kingdom in Scotland and a disastrous attack on Durham in England in 1039 CE tested the loyalty of his most powerful allies. One such man was his cousin Macbeth Macfinlay, mormaer (ruler or 'earl') of the region of Moray in the north of Scotland. Duncan and Macbeth met in battle at Pitgaveny in 1040 CE, and Duncan was killed. Macbeth took over the throne on 14 August. Meanwhile, Duncan's sons, Malcolm (b. 1031 CE) and Donald (b. c. 1033 CE), fled the country. It was a lucky escape, but when Malcolm reached adulthood he would prove to be Macbeth's nemesis.

Malcolm's Early Life

When Malcolm's world was turned upside down in 1040 CE, he sought safety in Northumberland in northern England. There he was looked after by Siward, earl of Northumbria (r. 1041-1055 CE) who had his own ambitions to acquire territory in southern Scotland. By the time Malcolm reached maturity, he had acquired another, even more powerful ally, the king of England, Edward the Confessor. The English king saw an opportunity to restore a Dunkeld to the throne and make Malcolm his puppet ruler.

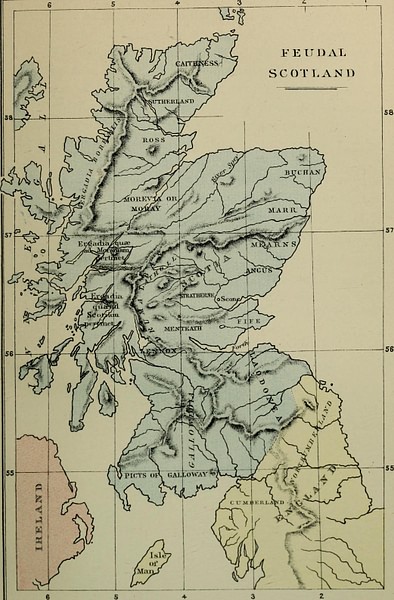

Macbeth's Scottish kingdom was far from unified. Sutherland and Caithness were still under Viking control. Another threat was the regular incursions in the north from Earl Thorfinn of Orkney (d. c. 1065 CE). Malcolm's grandfather Crinán, the lay abbot of Dunkeld led an uprising against Macbeth in 1045 CE. Crinán was defeated and killed but Macbeth's problems were only delayed. The next year Siward led an army into Scotland and defeated Macbeth. Siward may have briefly grabbed control of Lothian and perhaps Strathclyde before Macbeth gathered a second army and drove Siward south. For now, the threat had been dealt with, but Macbeth's enemies were prepared to bide their time. Malcolm would have to wait eight more years to get the better of Macbeth.

The English Invasion of Scotland

In 1054 CE Edward the Confessor, Siward, and Malcolm joined forces, and an English army again invaded southern Scotland. Macbeth was defeated at Dunsinane (in Perthshire) on 27 July of the same year and so lost control of Perth and Fife. Then, in 1057 CE, Macbeth was fatally wounded in a skirmish at Lumphanan (Aberdeenshire) against a group of Malcolm's supporters. Macbeth was succeeded on 8 September 1057 CE by his stepson Lulach (b. c. 1032 CE), but Malcolm disputed his right to reign. Malcolm controlled most of southern Scotland, and he had Lulach murdered in an ambush at Essie in Strathbogie on 17 March 1058 CE. Malcolm became king as Malcolm III of Scotland, and the Dunkeld line was restored.

Forging a Kingdom

In 1059 CE Malcolm solidified his alliance base and married Ingibiorg, the widow of Thorfinn of Orkney, greatly helping to unify northern and southern Scotland. In the same year, he visited - or was obliged to attend - the court of Edward the Confessor to swear his loyalty. Details of Malcolm's reign are scarce, but his one defining achievement was to better unify Scotland, as the historian D. Crouch here notes: "Máel Coluim's adroit handling of his multilingual collection of realms did more than anything else to define in contemporary consciousness the kingdom of Scotland out of Alba, Lothian, Galloway and Moray" (24). It is for this reason that Malcolm became known as Malcolm Canmore, from the Gaelic ceanmor, meaning 'Great Head' or 'Chief'. The king was able to maintain a sizeable infantry army through military service and to raise money from taxes. Not content with this, Malcolm also harboured ambitions south of the border, and he raided Northumberland in 1061 CE, looting the monastery at Lindisfarne. This was a continuance of a wide and deep border dispute between England and Scotland that rumbled on and off throughout the medieval period.

Queen Margaret

One of the most significant actions of Malcolm's reign was the king's decision to marry again in 1070 CE, about one year after the death of Ingibiorg. His choice was Margaret, an Anglo-Saxon princess who in 1068 CE fled her native country following the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 CE. Margaret was a keen supporter of the Catholic Church, and her promotion of it continued the demise of Gaelic Christianity in Scotland. Malcolm's reign saw an increase in Anglo-Saxon influence in Scotland as the king seems to have bent to his queen's wishes in most things. He allowed his children to be given Saxon names, permitted English to replace Gaelic as the language of the court at Dunfermline, and invited English monks and priests into his kingdom. He himself spoke English, Gaelic, and Latin. Margaret was made a saint in 1250 CE for her efforts to spread Roman Catholicism and charity work for the poor. For this reason, she is today better known as Saint Margaret of Scotland.

Edgar Ætheling & William the Conqueror

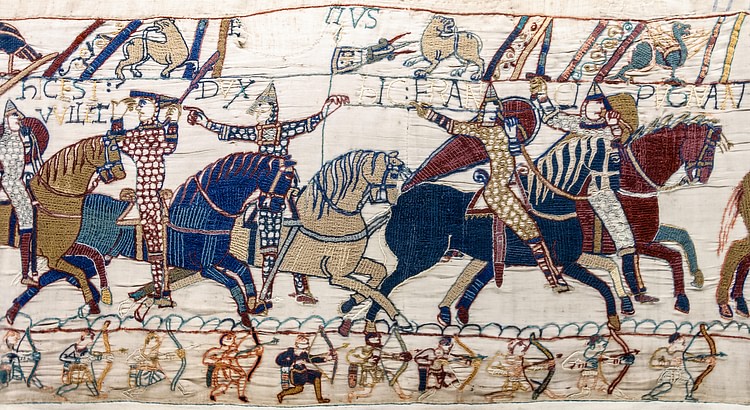

Margaret brought to Scotland one other important consideration. She was the elder sister of Edgar Ætheling, son of Edward the Exile (d. 1057 CE), great-grandson of King Ethelred II of England (r. 978-1013 & 1014-1016 CE), and the great-nephew of Edward the Confessor. Edgar had missed out on inheriting the throne of England from Edward the Confessor in 1066 CE because he had then only been in his teens and the Saxon lords had preferred to back the military experience of Harold Godwinson (r. Jan-Oct 1066 CE). When the Norman duke William the Conqueror took over England in 1066 CE and declared himself king, Saxon rebels chose Edgar as their figurehead and candidate number one to replace the Conqueror, now crowned William I of England. The Normans proved impossible to shift, though, and William secured his new throne by defeating rebellions in various parts of his realm, including the north of England. Edgar did not give up hope and sought shelter with his future brother-in-law Malcolm, taking with him his mother and two sisters Margaret and Christina.

Harbouring a serious rival to the English throne proved to be a very dangerous strategy, especially against such an accomplished military leader as William the Conqueror. Further, any children of Malcolm and Margaret might well later claim a right to the English throne. Several times already Saxon and Danish lords had combined to see if they could wrest the north of England from Norman control. Edgar Ætheling was usually their nominal figurehead and cloak of legitimacy, for he, they claimed, was the rightful king of England. In 1070 CE Malcolm unwisely ravaged Yorkshire. William eventually put an end to the troublesome raids on northern England with a combined land and sea operation in 1072 CE. Scotland itself was threatened, and Malcolm, whose army was no match for the disciplined Norman cavalry, sued for peace before any battle broke out. The terms, known as the Abernethy agreement, included Malcolm swearing allegiance to William as the superior monarch, providing his son Duncan as a hostage, and ensuring Edgar's exile to Flanders (where died in obscurity around 1125 CE).

Death & Successor

Malcolm never could resist the tempting riches of Northumbria, though. It was a short-term strategy that brought plunder but no lasting territorial gains. He attacked in 1079 and again in 1090-1 CE. William I's successor, his son William II of England (r. 1087-1100 CE), responded with more castle-building, including one at Carlisle. In 1091 CE William II sent a fleet to attack Scotland, but it was wrecked in storms off the coast of Northumberland. Nevertheless, a land army ravaged the Scottish lowlands sufficiently to force another formal declaration of submission from Malcolm. In the event, it was William II who broke this latest agreement when he annexed the region of Carlisle and part of Cumbria in 1092 CE. Malcolm travelled to meet William II in Gloucester in August 1093 CE to air his grievances, but the Norman king refused to see him, perhaps in a deliberate provocation to finally settle the disputed territorial borders between the two kingdoms.

It was during a third Scottish raid on Northumberland in late 1093 CE that Malcolm was killed in an ambush on 13 November at the gates of Alnwick Castle. Malcolm was misled into thinking the castle was about to be surrendered following a siege, but he was fatally stabbed in the eye. The king's son Edward was fatally wounded, too, in the same deception. Queen Margaret, then in Edinburgh castle, died on 16 November shortly after hearing the terrible news. There then began a reaction against the anglicisation of Scotland, and Malcolm's other children with Margaret - including Edgar (b. c. 1074 CE), Alexander (b. c. 1077 CE), Edith (1080-1118 CE) and David (b. c. 1084 CE) - were forced into exile in England. Malcolm III's remains were buried at Tynemouth but subsequently reinterred at Dunfermline.

As a consequence of the hostility against the dead king's immediate family and entourage, Malcolm's younger brother inherited the throne and became Donald III of Scotland. Donald's reign was interrupted in 1094 CE by his nephew Duncan (the son of Malcolm and Ingibiorg, b. c. 1060 CE), who became Duncan II of Scotland (r. May-Nov 1094 CE). Donald then regained the throne after Duncan II's murder and ruled on until 1097 CE. In that year, Malcolm III's son Edgar returned to Scotland and took back the throne from his uncle. Edgar had the support of William II who wanted a more peaceful neighbour and so he became Edgar, King of Scotland (r. 1097-1107 CE). The dethroned Donald III was blinded and imprisoned until his death. Malcolm III's other two surviving sons would, in turn, inherit the throne as Alexander I of Scotland (r. 1107-1124 CE) and David I of Scotland (r. 1124-1153 CE). The Dunkelds, now as the branch historians sometimes call the House of Canmore, would continue to rule Scotland until the death of Alexander III of Scotland (r. 1249-1286 CE). Meanwhile, as the royal houses of England and Scotland became closer allies; in 1100 CE, Malcolm III's daughter Edith became the first queen of Henry I of England (r. 1100-1135 CE) and changed her name to a more suitable Norman one, Matilda. Thus, the two kingdoms enjoyed, if only for the moment, peaceful relations.