The Manila galleons were Spanish treasure ships which transported precious goods like silk, spices, and porcelain from Manila in the Philippines to Acapulco, Mexico, between 1565 and 1815. The Atlantic treasure fleets then shipped some of these goods – along with silver, gold, and other precious materials extracted from the Americas – on to Spain. The Manila galleons, meanwhile, returned to the Philippines each year loaded with silver to buy more goods for the next trip. Manila galleons going in either direction were a floating Aladdin's cave of treasures and so they tempted many a pirate and privateer but, such was their armament, only four were ever captured at sea.

The Spanish Empire

In the 16th century, two European powers were colonising the globe. The 1529 treaty of Zaragoça (Saragosa) between Portugal and Spain extended the astonishing division of the world these two nations had previously established in the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494. The Zaragoça treaty confirmed Portugal's claim over the Spice Islands while Spain was given the Philippines. From 1565, galleon ships were used to transport trade goods, gold, and silver accumulated at Manila from across Asia to the Americas and then to Spain.

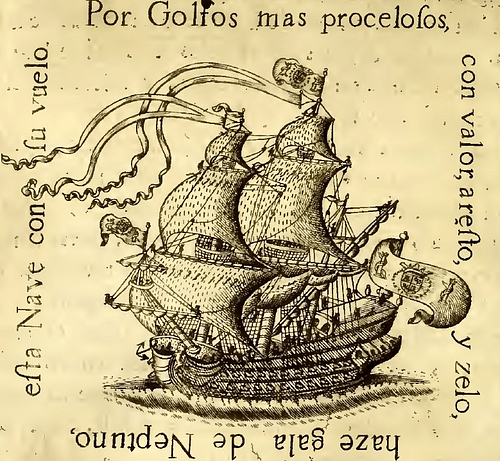

Unlike other ships, such as those of the Portuguese Empire which used the Cape of Good Hope trade route around the tip of southern Africa, the Spanish preferred to send their ships eastwards to the Americas. The one, or more rarely two, annual Manila galleons arrived at Acapulco on the Pacific coast of what is today Mexico and which was then part of the Spanish Empire in the Americas, the Spanish Main. Setting off from Manila in the Philippines, these ships became known as the Manila galleons to the British, although the Spanish themselves called them the naos de China or 'Chinese ships'. Almost all Spanish galleons operating in the Pacific were built in the Philippines, a requirement enforced by law from 1679, and they were funded and owned by the Spanish Crown.

Crossing the Pacific

The journey was a perilous one, with galleons usually leaving in June or July and using the trade winds to sail in a high arc that often crossed the 40th parallel. The Kuroshio Current, which originates in Taiwan, contributed another welcome push in the right direction. Despite these natural aids, it was not uncommon for a galleon to have to turn back to Manila if a series of storms was encountered or if the ship was too unwieldy because it had been overloaded with cargo. The long voyage to the Americas was memorably described by the Italian Gemelli Careri who made the crossing at the end of the 17th century:

The voyage from the Philippine Islands to America may be called the longest and most dreadful of any in the world, as well because the vast ocean to be crossed being almost one half of the terraqueous globe, with the wind always ahead, as for the terrible tempests that happen there, one upon the back of another, and for the desperate diseases that seize people in 7 or 8 months, lying at sea sometimes near the line, sometimes temperate, and sometimes hot, which is enough to destroy a man of steel, much more flesh and blood, which at sea had but indifferent food. (Giraldez, 119)

Not for nothing then did Spanish galleons have the letters AMGP painted on their sails. These letters represented the opening four words of the Hail Mary prayer: Ave Maria, gratia plena…

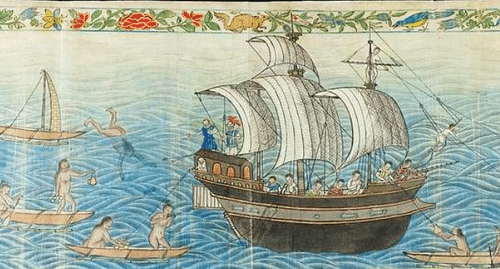

The voyage to the American continent, which was the ships' first sight of land, generally took six months, although it might take four or eight depending on wind and sea conditions. The galleons carried around 40 paying passengers as well as cargo, although no foreigners were permitted passage unless they acted as officers on the ship. With a poor diet and disease rife, it was not uncommon for 50 to 150 souls to die at sea during the voyage. When the galleons finally hit land in what is today Oregon or California, they then worked their way south following the coast, although not too closely since the indigenous peoples were extremely hostile to any interlopers in their territory.

The Cargo

The Manila galleons carried cargo like rolls of silk, Chinese porcelain, Persian carpets, jewellery, medicines, and rolls of Indian cotton cloth. There were exotic spices like cinnamon, clove, mace, and pepper, and perfumes like musk. There was always a quantity of gemstones, uncut precious stones, and Chinese gold bullion (which was worth much more in the Americas and Europe), and often a number of slaves, too.

The cargo was stored below decks in galleons that could weigh in at up to 2,000 tons, although most were around 1,000. The cargoes were unloaded into the Acapulco storehouses. Officially, the goods could only be sold in Mexico, but traders did re-export what they could get away with. Merchants made anywhere from 150 to 200% profit on their investment. A roll of silk, for example, was worth 10 times more in the Americas than in Manila. The Spanish Crown received a cut of the trade, as did the factors who brokered the deals in port. Officers might also make a handsome profit above their salaries by selling goods they had brought across in their personal luggage allowance. Goods not sold at the Acapulco trade fairs were transported by land to Veracruz on the Atlantic coast which had been founded by Hernán Cortés in 1519. There they might be sold or, in the case of Chinese porcelain, silk, and cottons, transported in the annual treasure fleet that sailed to Havana and then Spain. Such was the demand, manufacturers in Asia adapted their output. Ming porcelain was already highly collectible and much sought-after by Europe's aristocracy, so much so, Chinese potters began to produce designs which were most popular in that market.

The Return to Manila

After maintenance and repair works were carried out, a galleon was ready for the return journey back to the Philippines, typically carrying up to 3 million silver pesos to buy goods to fill up the hold again. A conservative estimate for the total quantity of silver shipped from Mexico to Manila throughout the 17th century is 55 metric tons. Silver was much more valuable in East Asia than it was elsewhere in the 16th century. For example, 1 oz of gold bought 11 oz of silver in Amsterdam while the same silver in China could be re-exchanged for 2 oz of gold. Other cargo included relatively small quantities of cacao, cochineal dye, wine, and olive oil. The galleons typically left Acapulco in March or April and used the trade winds to reach Guam and then the Philippines. The journey was much easier in this direction and took about three to four months.

Threats & Captures

The Manila-Acapulco galleons were an obvious temptation for foreign powers and their privateers. Pirates, too, dreamed of taking a ship that could result in every crew member grabbing a lifetime's wages in a single day. In the early days, before the Pacific waters attracted other European ships on the prowl for loot, the galleons went unarmed, but the Spanish quickly remedied this oversight. Galleons could present a formidable array of up to 60 cannons below and above deck, and they carried large crescent blades fixed to the yardarms which were designed to cut the sails and rigging of any ship that dared get alongside. The elevated superstructures at the stern and bow of a galleon provided marksmen with an excellent platform above an enemy ship.

As a consequence of these defences, and despite usually travelling the High Seas unescorted, only four Manila galleons were ever captured at sea in over 250 years of service. The ships were, first of all, very difficult to find in the open sea, and even pirate vessels that loitered around the American coast for many weeks usually failed to find them. Even if they were found, a galleon was far bigger and far better-armed than any pirate vessel and even most naval ships. Further, they had large crews of around 100 men in the 16th century and up to 250 in the 18th century. Crews were usually made up of Filipinos, Chinese, Mexicans, and Spaniards. There was, too, a contingent of professional soldiers led by a war captain. Also, plenty of the passengers were armed and willing to risk life and limb to protect their valuables. Finally, the galleons were built of Eastern hardwoods which made their hulls remarkably resistant to cannonballs. In effect, a galleon was a slow-moving but formidable castle on the sea. It was far more likely to be sunk by storm, reef, or accidental fire than an enemy attack. At least 30 Manila galleons were shipwrecked in one way or another over the years.

In addition to all of these difficulties, Acapulco itself was strongly fortified from 1617 with the construction of the San Diego Fort, a five-sided structure with six angled bastions. By 1697, the fort's garrison manned 42 cannons. In addition, being on the 'wrong' side of the continent for most European ships, Acapulco remained a relatively safe harbour for the galleons. Most raiders preferred to attack the final American destination for these rich trade goods: Veracruz on the Atlantic coast. Finally, a system of warning beacons was instigated along the coast of Mexico to warn an incoming galleon that enemy ships were prowling the area.

Thomas Cavendish (1560-1592) was one of the lucky raiders who grabbed a Manila galleon. Working his way up the coast of North America, the English privateer came across the single greatest prize capture of his epic circumnavigation of 1586-8. The carrack Great Santa Ana was on its way from Manila and was loaded with 22,000 gold pesos and 600 tons of precious silks and spices. It was sighted by Cavendish's men on 14 November 1587 off the coast of California and attacked over a period of six hours. The ship was personally owned by Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598) and so Anglo-Spanish relations plummeted to a new low following its loss.

The English privateer Woodes Rogers (1679-1732) grabbed his Manila galleon on New Year's Day 1710 while he, too, was circumnavigating the globe. He captured the Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación Disengaño and its lucrative cargo off the coast of North America. Rogers had tried to take the galleon's larger companion ship, the Begoña, a few days later, but his four ships, firing over 500 cannon shots, were still not enough to prevent the Begoña's escape.

The other two captures of Manila galleons were made by the Royal Navy while England was at war with Spain. In 1743, the galleon Covadonga was taken by George Anson who commanded a powerful frigate armed with 60 cannons. The galleon was carrying 1.3 million silver pesos from Acapulco and was not far from the safety of Manila when it was boarded. The fourth and final capture was made in 1762 by a British fleet commanded by Admiral Cornish which relieved the galleon Santísima Trinidad, whose masts had been broken in a storm, of its cargo destined for Acapulco, a haul worth over 2 million silver pesos.

The End of the Manila Galleons

The Manila galleons remained vital to Spain's trade within its empire until around 1785 when the Philippines were finally opened up to other European traders. The galleons continued to regularly sail for Mexico until 1811 when Mexican rebels took control of Acapulco. The Spanish Crown decreed an end to the route in 1813, but one final Manila galleon, the San Fernando, sailed to Acapulco in 1815.

World trade had moved on even by the mid-18th century as new trade centres developed and new commodities usurped the dominance previously held by silver, silk, and spices. The United States, Brazil, India, and China were the new big players, trading such lucrative goods as tea, opium, sugar, tobacco, coffee, and cotton in massive quantities worldwide. The Manila galleons of the Spanish Empire had certainly played their part in transporting goods and ideas from one culture to another and had even been responsible for the significant movement of populations, whether it be Peruvian traders to Mexico or Chinese manufacturers to Manila. By the 19th century, though, they had become a part of maritime history, victims of the process of globalisation in trade they had themselves helped begin.