Martin Bucer (l. 1491-1551) was a German reformer and theologian who had been a Dominican friar and priest until converted to the Protestant vision by Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) c. 1518. Bucer is best known for his focus on unity among all Christians, and consequently, he never established his own sect but influenced many.

Like other reformers, Bucer was drawn to the works of the humanist theologian and scholar Desiderius Erasmus (l. 1466-1536) before hearing Luther speak in 1518. Erasmus' humanism, in fact, convinced Bucer that Luther's views were acceptable even though Luther and Erasmus disagreed on many significant points. After leaving the Dominican order in 1521, Bucer preached the Protestant view and embraced the new movement, marrying the former nun Elisabeth Silbereisen in 1522.

He was taken under care by the Reformed pastor Matthew Zell (l. 1477-1548) and, later, his wife Katharina Zell (née Schütz, l. 1497-1562) of Strasbourg and became one of the most prominent theologians and pastors of the city, always emphasizing the importance of unity among the Protestant sects developing there and elsewhere, and was co-author of the Tetrapolitan Confession (also known as the Strasbourg Confession) with Wolfgang Capito (l. c. 1478-1541), which presented a unifying confession of faith for the Reformed Church. He also attempted to mediate the dispute over the Eucharist between Martin Luther and Swiss reformer Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531), though without success.

When the Augsburg Interim went into effect in 1548, forcing cities in the Holy Roman Empire to return to Catholicism, Bucer accepted the invitation of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (l. 1489-1556) and left for England where he was instrumental in revising the Book of Common Prayer and contributing to Reformation efforts in other ways. He died of natural causes in England at the age of 59. His insistence on unity of vision for all Protestant sects meant that he never felt compelled to establish his own, but his works influenced Lutherans, Zwinglians, Anglicans, and many others who, today, claim him as one of their own.

Education & Conversion

Bucer was born to a family of coopers (barrel makers) in Selestat, Alsace, in 1491. Nothing is known of his early life, whether he had siblings, or his mother's name. His father and grandfather were both named Claus Butzer, and Bucer's last name is sometimes given this same spelling. His parents were almost certainly well-off as he was educated instead of apprenticed in his father's craft, learning Latin at the local school. Here, he may have met the humanist and later reformer Beatus Rhenanus (l. 1485-1547), also a native of Selestat, who attended the same school and is later referenced as Bucer's mentor. Bucer graduated Latin school and, in 1507, he entered the Dominican order and was ordained a deacon in 1510.

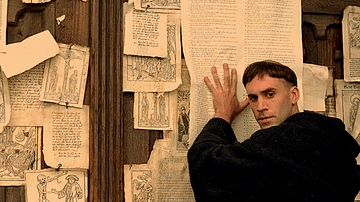

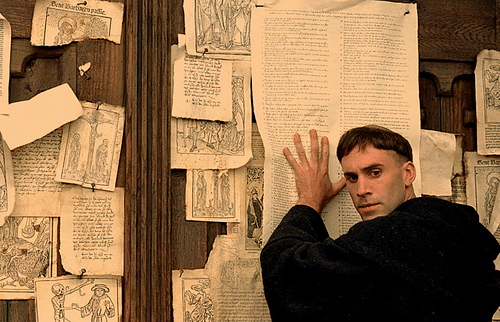

He was a student in Heidelberg by 1515, studying for the priesthood, and was ordained at Mainz in 1516, then returned to Heidelberg where he immersed himself in the scholasticism which was then considered essential for a priest's education. He was especially drawn to the works of Thomas Aquinas (l. 1225-1274), who had also been a Dominican, and then those of Erasmus. In 1517, Martin Luther's 95 Theses were posted, and the movement that became the Protestant Reformation was launched in Wittenberg, which drew Bucer's attention by 1518.

In April of 1518, Luther came to Heidelberg to lecture on his views at the Heidelberg Disputation and Bucer met and spoke with him, concluding that he was right in rejecting the teachings of the Catholic Church. Prior to the 95 Theses, Luther's 97 Theses had been published, arguing against the scholasticism Bucer had embraced. Bucer wrote to Rhenanus at this time expressing his concerns over associating with Luther but, at the same time, explaining how Luther's views were supported by the works of Erasmus, a scholar Rhenanus knew personally. Rhenanus' humanist views may have influenced Bucer early on, possibly encouraging his interest in Erasmus and acceptance of Luther, but this is unclear.

By 1519, Bucher had received his bachelor's degree from Heidelberg and fully embraced Luther's vision, rejecting his former interest in scholasticism. Having publicly supported Luther's position, Bucer was targeted by the Dominican Inquisition but was able to avoid persecution by having his vows to the order annulled in 1521. He was still considered a threat by authorities, however, but was protected by two powerful knights who also supported Luther's cause, Ulrich von Hutten (l. 1488-1523) and Franz von Sickingen (l. 1481-1523), best known for their leadership of the Knights' Revolt (1522-1523). During this time, Bucer was closely associated with the Lutheran movement, offering his support to Luther at the Diet of Worms, though his assistance was not asked for nor appreciated.

Diet of Worms

Luther was summoned to appear at the Diet of Worms in April 1521 by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, to explain his views and, hopefully, recant. Charles V was interested in restoring unity to his territories, and Luther's 'new teachings', as they were called, were an obstacle to this. The emperor gave Luther a promise of safe conduct to Worms from Wittenberg for 20 days from the day he received the mandate to appear. According to Luther's later works, Bucer intervened as they neared the city, trying to persuade Luther not to enter as his works were being burned there and so, Bucer feared, would Luther be himself. Luther rejects Bucer's alleged good intentions in his later account:

When I arrived at Oppenheim, near Worms, Master Bucer came to see me, and tried to dissuade me from entering the city. He told me that Glapion, the emperor's confessor, had been to him and had entreated him to warn me not to go to Worms; for that if I did, I should be burned. I should do well, he added to stop in the neighborhood, at Franz von Sickengen’s, who would be very glad to entertain me.

The wretches did this for the purpose of preventing me from making my appearance within the time prescribed; they knew that, if I delayed only three more days, my safe-conduct would have been no longer available and then they would have shut the gates in my face, and, without hearing what I had to say, have arbitrarily condemned me. (Michelet, 79)

Luther rejected Bucer's suggestion and continued on to Worms, where he gave his famous "Here I Stand" speech. Luther's speech at the Diet of Worms signaled his complete break with the Catholic Church and became a rallying point for his followers, among whom was Bucer.

It seems unlikely that Bucer, who had already left the Dominican order and whose own life had been threatened, would have purposefully tried to keep Luther from attending the assembly, but this is how Luther interpreted his intervention. Scholar Lyndal Roper notes that Bucer's suggestion enraged Luther and "he mistrusted Bucer forever after, which would have wide-ranging consequences" (167). Bucer seems to have had no idea he had offended Luther and, according to scholar Thomas Kaufmann, identified himself completely with Luther's cause:

In many respects, Martin Bucer represents the ideal type of "Lutheran" of the early period. Like Luther, he came from a mendicant order, in his case that of Saint Dominic. Like most other Reformers, he had received a rigorous Humanist education and had discovered Luther via the "detour" of Erasmus. Similar to other Humanists, he admired Luther's biblical commentaries tremendously; he transmitted news about the Wittenberg Reformer and disseminated his texts. (Rublack, 153)

It is unclear how Luther concluded that Bucer was in league with his enemies, but his animosity toward Bucer is thought to have played a part in his later rejection of unification with Zwingli at the Marburg Colloquy and the Diet of Augsburg.

Marriage & Excommunication

Following Worms, and still under the protection of Hutten and Sickingen, Bucer was employed as a chaplain by the progressive Elector Louis V, Count Palatine (l. 1478-1544), and lived in Nuremberg, where, among others, he met Andreas Osiander (l. 1498-1552), the reformer who would encourage the publication of the works of Argula von Grumbach (l. 1490 to c. 1564). Sickingen was a leading figure at the court of Louis V, had offered to take Luther under protective custody after Worms, and had made the same offer to Bucer. He finally convinced Bucer that he would be safer at his castle in Landstuhl, and Bucer moved there in early 1522. Soon after, he met and married the former nun, Elisabeth Silbereisen.

The conflict later known as the Knights' Revolt was gaining momentum at this time, and Sickingen, probably thinking Bucer would be safer elsewhere, sent him to study in Wittenberg, which, by 1522, was a safe haven for Lutherans. He stopped in Wissembourg on his way and was persuaded by the reformer Heinrich Motherer to stay and accept a position as chaplain. Bucer's sermons against church policy and, especially, the interpretation of the Eucharist, encouraged revolts against ecclesiastical authority, and Bucer was officially excommunicated by the bishop of the region.

By this time, early May 1523, the Knights' Revolt had been crushed, Sickingen was dead, and Hutten a fugitive who would only live a few more months. Deprived of his powerful protectors, Bucer left for Strasbourg, taking Motherer with him.

Strasbourg, Luther, & Zwingli

Bucer was taken under care by the leading Reformed priest of the city, Matthew Zell, and served as his assistant before accepting a position as pastor of St. Aurelia's Church in August 1523. In December 1523 he officiated the marriage of Matthew Zell and Katharina Schütz, and he continued to work with the Zells afterwards as all three shared the same ecumenical views of Christianity. He also worked closely with Wolfgang Capito and Caspar Hedio (l. 1494-1552), especially in organizing the Marburg Colloquy of 1529 which attempted to reconcile Luther's and Zwingli's differences.

Prior to that event, however, Bucer, Capito, Hedio, the Zells, and others advanced the cause of the Reformation in Strasbourg and Bucer became the eloquent champion in written defenses of Reformation ideals. Catholic opposition, in the form of the Augustinian prior Conrad Treger, condemned the reformers as heretics, but Strasbourg already supported the Reformation, and the city council sided with Bucer. Treger was arrested after his efforts to suppress the Reformation resulted in riots, and once released, he left the city. Bucer then published his Basis and Cause, establishing universal Protestant principles and explaining the rejection of Catholic doctrine, ritual, and practices. He made clear there was room for all within the Protestant vision as long as one approached God with sincere, childlike faith and understood scripture as God's word to humanity.

Although he adhered to Luther's vision of faith alone and scripture alone as the basis for one's relationship with God, he favored Zwingli's interpretation of the Eucharist. Zwingli held that the Lord's Supper was a commemoration of an event and Jesus Christ's spirit was present when it was celebrated but the bread and wine were not transformed into Christ's blood and body. Luther insisted on the actual presence of Christ in the Eucharist and refused to compromise as he believed that in doing so he was denying scripture.

In 1529, Bucer participated in organizing the Marburg Colloquy to resolve various differences between Luther and Zwingli but, primarily, their interpretation of the Eucharist. Luther and Zwingli agreed on all points presented except that one. Luther insisted on his own vision as God's vision, and Zwingli rejected this as mirroring the traditional teachings of the Catholic Church. Luther left the meeting after claiming Zwingli, Bucer, and anyone who did not agree with him were following false teachings. Bucer noted that the important aspects were faith alone and scripture alone and everything else could be left up to individual interpretation, but "scripture alone" was the stumbling block since Luther and Zwingli interpreted the passages relating to the Lord's Supper differently.

The next year, at the Diet of Augsburg of June 1530, Bucer again encouraged unity through the Tetrapolitan Confession he co-wrote with Capito, but this work, as well as Zwingli's Confession to the Emperor Charles, were overshadowed by the Augsburg Confession of Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560), Luther's right-hand man, which would become the model for other confessions and, naturally, expressed Luther's views. By this time, the division between the Lutherans and the Reformed Church of Zwingli, Bucer, and Capito had grown so wide that at first Melanchthon refused to even meet with Bucer and Capito at Augsburg but then relented and agreed to review a letter Bucer planned to send to Luther who was at Coburg because, having been branded an outlaw, he could not attend the Diet of Augsburg without being arrested and executed.

Bucer's letter pointed out that Luther claimed Christ was actually present in the Eucharist and that he and Zwingli and the others believed that Christ was spiritually present and so, really, there was no disagreement. It did not matter, Bucer claimed, whether Christ was physically present or spiritually present as long as the believer experienced that presence and was able to commune with God. Melanchthon was uneasy with the letter but sent it on to Luther, who rejected the argument completely. He wrote back to Melanchthon:

I won't answer Martin Bucer's letter. You know how I hate their games of dice and they slyness; they don't please me. This is not what they have taught up to now, but they will neither recognize it nor do penance, rather, they just continue to insist that there was no disagreement between us, so that we would have to admit that they taught truly but we had wrongly fought against them, or rather, that we were crazy. (Roper, 319)

As noted, it is thought that Luther rejected Bucer's efforts at unity, in part at least, because of the latter's intervention before the Diet of Worms. Luther began a series of attacks on Bucer in writing which Bucer refused to respond to citing the biblical admonition to "turn the other cheek" and to forgive others for transgressions as one had been forgiven.

Conclusion

Between 1530 and 1548, Bucer worked for the unification of the Protestant sects with sometimes more and oftentimes less success. Although he won Melanchthon to his side on significant points, he could not sway Luther. His relationship with Zwingli deteriorated when he would not take a firm stand against Lutheran beliefs. Zwingli had cut all ties with Bucer and, after his death in 1531, his successor, Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575), was at first wary of Bucer. Bullinger's First Helvetic Confession was, in part, an answer to Bucer's call for unity, but Bullinger did not fully support Bucer's efforts.

Bucer's wife, Elisabeth, and Wolfgang Capito died in 1541 when the plague struck Strasbourg, and he married Capito's widow, Wibrandis Rosenblatt (l. 1504-1564) in 1542 on the advice of Katharina Zell. Bucer had reformed the Strasbourg church and encouraged efforts elsewhere when the Augsburg Interim was declared by Charles V in 1548 mandating a return to Catholic teachings and practice throughout his realm. Bucer left for England, accepting the invitation of the Reformed archbishop Thomas Cranmer, and took a position teaching at Cambridge University.

The English Reformation encouraged just as many divisions as the movement had in Germany and elsewhere, and since Bucer was known as a moderate who had effected reforms in Strasbourg, he was asked to take sides. He refused, however, maintaining – as he had all along – that Christianity should be all-inclusive and welcoming to diverse interpretations, and details such as the Lord's Supper, the wearing of vestments, or any other source of division should be regarded as secondary to one's confession of faith in Christ and how one lived that faith in a Christ-like spirit, trusting in God and encouraging one's fellow Christians.

He died of natural causes in 1551 and was buried in the churchyard of Great St. Mary's. When Mary I of England (r. 1553-1558, known as 'Bloody Mary' for her persecution of Protestants) came to power and tried to restore Catholicism, she had Bucer and others tried for heresy, and his remains were exhumed and burned along with his works. His grave was restored under the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603) who also encouraged the translation and dissemination of his works.

Scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch notes how "Bucer talked a good deal more about the love of God than did many of his fellow Reformers. Moreover, he was capable of seeing the good in people who were deeply at odds" (180). He never established his own sect of Protestant Christianity because, to Bucer, there should be no sects, no division, only a single – and simple – devotion to the teachings and model of Christ. He advocated for the vision expressed in the Bible in Matthew 6:33: "But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness, and all these things shall be added unto you." In the present day, as shortly after his death, diverse sects have claimed him as supporting their interpretation of Christianity above others; a claim Bucer himself would no doubt disagree with.