Sir Martin Frobisher (c. 1535-1594 CE) was an Elizabethan adventurer and explorer who embarked on three expeditions in the 1570s CE to chart the waters of the North American Arctic and find the Northwest Passage to Asia. Unsuccessful in these endeavours and bankrupting many of his investors who had hoped to find gold deposits, Frobisher's later career was more military-focused as he participated in the war with Spain and the battle to repel the Spanish Armada of 1588 CE. Frobisher died in November 1594 CE after he was fatally wounded attacking a Spanish-held fortress in northern France.

Early Life

Martin Frobisher was born in Yorkshire in 1539 CE, the son of a member of the local gentry who had Welsh ancestry. Early in life, Martin was packed off to live with his uncle in London, Sir John York, who, significantly for Frobisher's later career, was a merchant who traded in exotic goods. From 1553 CE, Martin joined his uncle's and others' expeditions to acquire trade goods and indulge in less honourable pursuits such as privateering. One notable voyage was to Guinea, and other trips included the Barbary Coast of North Africa and the Middle East end of the Mediterranean. In the 1560s CE, the young adventurer was imprisoned in a Portuguese fortress on the coast of West Africa, served in Ireland as an agent of the Crown, and narrowly avoided a debtor's prison back home. This rather undistinguished early career then took an upturn as Elizabeth's chief minister William Cecil, Lord Burghley, took an interest in the adventurer and enrolled him in exploration for the Crown.

The First Northwest Passage Expedition

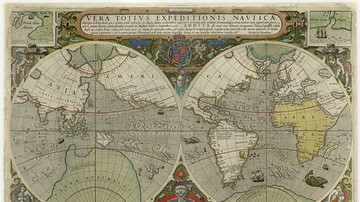

In 1576 CE, Frobisher embarked on his most ambitious project yet, to find the fabled Northwest Passage that, at least in summer, might lead through the freezing waters of North America and reach Asia with its lucrative silk and spice trade. Such a passage would avoid the lengthy and costly alternative of going around the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa or the more dangerous route around the tip of South America. To all intents and purposes, there was no Northwest Passage as the icy Arctic waters blocked any ships from that route but that did not stop a long list of explorers from trying their luck and making themselves the darling of all European traders. Frobisher persuaded a number of London merchants to finance his expedition. He also had the backing of such distinguished figures as Cecil mentioned above and the courtier Sir Humphrey Gilbert (c. 1539-1583 CE), the astrologer, mathematician and geographer John Dee (1527-1608 CE) and Ambrose Dudley, the Earl of Warwick (c. 1528-1590 CE).

The pinnace had already been lost in a storm prior to Baffin Island, and the Michael returned to England thinking Frobisher and the Gabriel had sunk. This was not the case, and Frobisher pushed on northwards. Mistakenly and rather optimistically thinking he had reached the coast of Asia, Frobisher named the inlet which led hopefully westwards the Frobisher Strait. The explorer then returned to England in October, but the Queen was unsure what to call such a strange white desert and so the name given was Meta Incognita or 'Unknown Frontier'.

Below is an extract from the diary of an officer on Frobisher's first expedition describing the meeting with Inuits:

In this place he [Captain Frobisher] saw and perceived sundry tokens of the people, resorting thither. And being ashore upon the top of a hill, he perceived a number of small things fleeting in the sea afarre off, which he supposed to be porposes or seales, or some kind of strange fish; but coming neere, he discovered them to be men in small boats of leather…Afterwards he had sundry conferences with them, and they came aboard his ship, and brought him salmon and raw flesh and fish…They exchanged coats of seales, and beares skinnes, and such like, with our men; and received belles, looking glasses, and other toyes, in recompense thereof againe. After great curtesie, and many meetings, our mariners, contrary to their captaines direction, began more easily to trust them; and five of our men going ashore were by them intercepted with their boat, and were never since heard of to this day againe.

(Courtauld, 57)

Second Expedition

Having returned to England on 2 October 1576 CE and brought back what were thought by some experts to be examples of gold-bearing ore, the explorer easily managed to convince a consortium of investors to fund a second expedition to investigate the Arctic region more thoroughly. The Company of Cathay was duly formed with even Elizabeth contributing £1,000 and giving Frobisher a new ship, a 200-ton man-of-war named Aid. The Michael and Gabriel were also made ready for their return to the North Atlantic. This time the expedition would include a number of miners to see if Meta Incognita was indeed a land of mineral wealth. The explorer set off again in the last week of May 1577 CE, this time determined to find either gold, the Northwest Passage, or both.

Below is another extract from an officer's diary, here describing the foul weather the second expedition encountered:

Here, in place of odoriferous and fragrant smels of sweete gums, and pleasant notes of musicall birdes, which other Countreys in more temperate Zones do yeeld, wee tasted the most boisterous Boreal blasts mixt with snow and haile, in the moneths of June and July, nothing inferior to our untemperate winter…All along this coast yce [ice] lieth, as a continual bulwarke, and so defendeth the Countrey, that those that would land there, incur great danger.

(ibid, 58-9)

Arriving for a second time at Baffin Island, the miners got busy and loaded the ships with 160 tons of what they hoped was precious ore. Once again, a number of Inuit were met and this time painted by the expedition's artist and cartographer John White (d. 1593 CE). Some Inuit were forcibly kept on the ships and there was a skirmish when the Inuit attacked a number of seamen with their bows and arrows. Five Inuit were shot dead, and Frobisher himself was struck by an arrow in the behind. The explorers returned to England in September 1577 CE.

Third Expedition

After more mineral experts had satisfied themselves the ore Frobisher had brought back did contain gold (although many other experts thought not), the explorer found financial backing for a third expedition. Again Queen Elizabeth contributed to the enterprise and so did her notoriously tight-fisted Lord Burghley. This new effort was far larger than the first two expeditions and consisted of a fleet of 15 ships. A group of Plymouth miners also joined the team. Setting off on 31 May 1578 CE, the expedition landed on southern Greenland - which they called West England - but met with little success going further north due to storms, unusually cold summer temperatures, and the sea made perilous by sea ice and icebergs. The 100-ton Dennys was sunk by an iceberg and the Thomas' crew decided to mutiny and return straight home. The bad weather and conditions caused the fleet to be separated and much time was wasted in trying to regroup.

In this third extract from the officer's diary, the awful conditions on board are described that terrible third summer:

In this storme being the sixe and twentieth of July, there fell so much snow, with such bitter cold aire, that we could not scarce see one another for the same, nor open our eyes to handle our ropes and sayles, the snow being over halfe a foote deepe upon the hatches of our ship…every man perswading himselfe that the winter there must needes be extreme, where they found so unseasonable a Sommer.

(ibid, 67-8)

Frobisher pressed on and accidentally made the single most important discovery of his three expeditions when his fleet was blown into what we today call the Hudson Strait on 7 July. Frobisher called this the 'Mistaken Strait' but realised it was a far more likely candidate for an eventual Northwest Passage than the much smaller Frobisher Strait. The explorer sailed 320 kilometres (200 miles) up the Strait but then turned back, mindful that his financial backers had been adamant that the real purpose of this third expedition was to find gold-bearing ore. Frobisher had also been commanded to leave 100 men behind to form a tentative colony but as he had lost with the Dennys the prefabricated huts intended to provide them with accommodation, the idea was abandoned.

On returning to England with another load of ore, it was eventually discovered that all the rocks Frobisher had brought back to England contained nothing of any value, their yellow mica content having been mistaken for gold. The Company of Cathay investors lost some £20,000, and Frobisher's dream of a fourth expedition seemed an impossible one. Yet, in 1579 CE Frobisher was made captain of another ship destined for the frigid north but as the aim of the expedition was solely trade and not exploration, he withdrew from the project.

Frobisher's exploration had achieved very little but it was, at least, a beginning. In 1578 CE Sir Francis Drake (c. 1543-1596 CE) had a go at finding the Northwest Passage but he got only as far as what is today Vancouver. John Davis (aka Davys, c. 1550-1605 CE) explored the region again, making three visits between 1585 and 1587 CE, and achieved much more concrete geographical knowledge but the passage still proved elusive. Many more attempts were subsequently made by many different explorers but the navigation of the Northwest Passage would have to wait for the early years of the 20th century CE and the efforts of the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen (1872-1928 CE).

The War with Spain

Frobisher was not quite finished with the high seas and, after a spell of privateering in Irish waters, he sailed as vice-admiral with Sir Francis Drake in 1585 CE in an expedition to raid the Spanish West Indies. The Englishmen managed to disrupt the plans of Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598 CE) who was trying to build up his Spanish Armada to attack England. The destruction of supplies and capture of many cannons was a blow which resulted in Philip's Armada being large but not as huge as he had originally planned. Frobisher fought in the battles to repel the Spanish Armada in the summer of 1588 CE, commanding a squadron and the ship Triumph. After the victory, he was knighted by a grateful queen for his efforts. Frobisher was involved in further naval engagements and privateering in the Azores against the same enemy's New World treasure ships in the early 1590s CE.

In August 1594 CE Frobisher was given command of a small fleet which included the royal galleons Vanguard and Rainbow with orders to attack Spanish positions in northern France, now England's ally. Frobisher attacked the Spanish-held fortress of Crozon in Brittany, laying siege to it during September. The fortress was cut off from supplies by land when Frobisher put a force of soldiers and cannons on the peninsula. At the same time, English ships fired broadsides at the fortress from the sea. The thick walls of the fortress resisted the cannon shot, and it was only when a group mined under the walls that Frobisher could directly attack. It was in this assault that Frobisher was fatally wounded on 7 November. Shot in the hip, the explorer, sailor, and privateer made it back to Plymouth but, aged 59, he died from gangrene of the wound on 22 November 1594 CE. The historian H. Bicheno summarises Frobisher's colourful career thus:

Unrivalled as a combat leader, he was kept from greatness by his poor education and a crudely larcenous disposition that led him to cheat the queen - and his men - in the matter of rations, and to revert to petty piracy…his last years were embittered by a corrosive envy of Drake, who was so abundantly endowed with the star quality Frobisher sadly lacked.

(280)