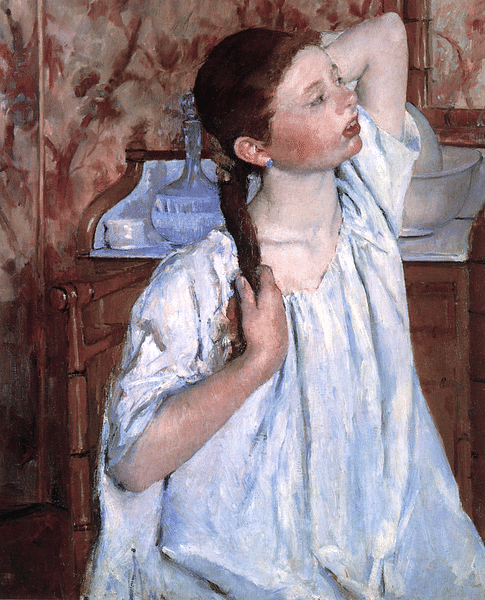

Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) was an American impressionist painter who lived most of her life in France. She focussed on capturing women at their daily tasks in oils, pastels, and prints, and produced many innovative representations of mothers and children. Cassatt was hugely influential in encouraging the exhibition and collection of impressionist art in the United States.

Early Life

Mary Stevenson Cassatt was born on 22 May 1844 in Allegheny City outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She was born into an upper-middle-class family, her father was Robert Simpson Cassatt, a highly successful stockbroker, and her brother Alexander would become a very wealthy railroad magnate and President of the Pennsylvania Railroad. In 1849, the family moved to Philadelphia. Between 1851 and 1855, Mary accompanied her family on a tour of Europe. Aged just 16, Mary began her studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Like many of the impressionists, she was disappointed with the more traditional teaching methods, and she decided to go her own way.

Cassatt moved with her mother and a friend to Paris in 1865 to study painting under Thomas Couture, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and Charles Chaplin (not the actor). Her studies were interrupted by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 when she returned to the United States. Back in Europe in 1871, Cassatt embarked on an extended cultural tour that took in the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, and Italy. She studied the art in public galleries and was impressed by such masters as Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and Correggio (1489-1534).

Eventually finding her way back to Paris, Cassatt again settled in the capital and set her sights on having a submission accepted by the Paris Salon, then the premier exhibition space for fine art. Her During the Carnival was accepted by the Salon in 1874, and two more paintings were selected the next year. All three works remind of Spain, then a vogue in picture painting known as Espagnolisme. In 1877, the Salon rejected a portrait Cassatt had sent for consideration, and this disappointment may have been the catalyst for her to explore other avenues, ones where she could work "without considering the opinion of a jury" (Roe, 186).

The art historian S. Roe gives the following memorable physical description of Cassatt:

Mary Cassatt was tall and imperious, with a tiny waist, small eyes and a strong jawline. She was certainly not conventionally pretty, but as she quite reasonably remarked to [her friend] Lousine, that was hardly her fault. She dressed immaculately in the latest svelte, tailored fashions, smart boots and chic hats, and held herself very straight. She had a loud voice... [and] an atrocious accent when speaking French.

(183)

Influences & Style

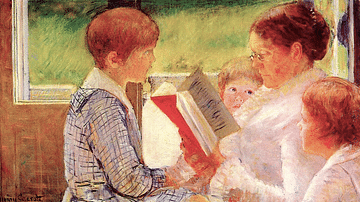

Cassatt was keen to find out more about the new avant-garde artists who were causing such a stir in the art world. Fluent in French, she became good friends with many of her fellow impressionists. She was close to Edgar Degas (1834-1917), whom she met around 1875. Cassatt was the model for several of Degas' paintings, notably Mary Cassatt at the Louvre (1885) where she is shown from behind admiring ancient Egyptian artefacts. She crops up, too, in many of Degas' pastels of milliner shops, no doubt, because of Cassatt's own taste in fine hats. Cassatt was also friends with Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), and she even visited the reclusive Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) at his home in Aix-en-Provence in 1894. Cassatt, along with Morisot, added a new dimension to the impressionist movement since they often chose as their subjects more feminine activities and presented real women living real lives (as opposed to the sometimes idealised view of women the male artists sometimes gave). Cassatt and Morisot show us women at leisure, reading, taking tea, enjoying the opera, and caring for their children. The latter particularly interested Cassatt since she found them "so natural and truthful. They have no arrière pensée [ulterior motive]" (Roe, 184).

The subjects may have been slightly different, but Cassatt's artistry is on a par with the male impressionists. Degas, describing her craft, once noted her "reflections and shadows on skin and costumes for which she has the greatest feeling and understanding" (Howard, 165). Cassatt created images which were a blend of strong composition with a tender emotional insight.

The art historian M. Howard gives the following summary of the mature Cassatt style:

Her work reveals a strong decorative sensibility, combined with a particular fondness for unusual perspectives, asymmetrical compositions, clean coloration, sharp incisive drawing, and a shrewd and sympathetic characterization of her subjects.

(163)

Mary Cassatt: A Gallery of 30 Paintings

The Impressionist Exhibitions

Cassatt was invited to participate in the fourth edition of the Paris Impressionist exhibitions, 1874-86. In April and May of 1879, over 260 works by 15 artists were on display. There were oil paintings, pastel works, and painted fans (thought to be more saleable). An innovation for this exhibition was the use of coloured frames for certain works when it was considered complementary to the art. For example, Cassatt's Woman with a Fan was given a vermilion frame, and her Box at the Opera a green one. The exhibition was the most successful so far in terms of visitors – some 16,000 – and money, with each artist receiving a dividend of 439 francs. With her share, Cassatt bought a painting by Monet and one by Degas. She would return in the fifth edition in 1880 (which she helped to fund), the sixth in 1881 (when she was one of the few artists to receive favourable reviews), and the eighth and final impressionist show in 1886.

It had been a long and sometimes fierce battle to put on the independent exhibitions and have impressionism recognized as something of value, as Cassatt once noted in a letter:

There are so few of us that we are each required to contribute all that we have. You know how difficult it is to inaugurate anything like independent action among French artists, and we are carrying on a desperate fight and we need all our forces, as every year there are new deserters.

(Howard, 96)

As noted, some critics did eventually come around and rally to the cause. Cassatt's work in the sixth exhibition drew the following comments from Joris-Karl Huysmans in L'Art Moderne: "There has arisen an artist who owes nothing to anybody, an artist who at first attempt has established her personality" (Howard, 100).

Printing

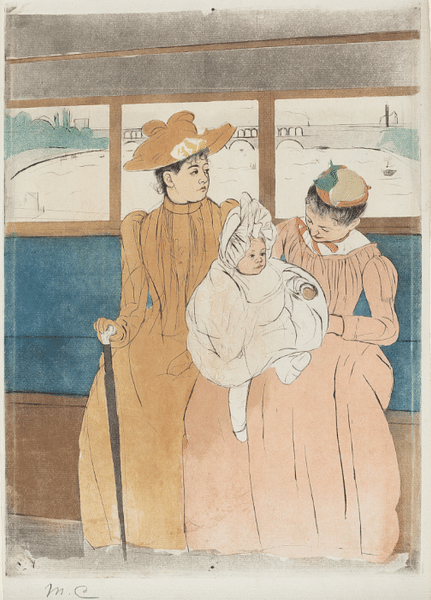

Cassatt was influenced by Japanese art from the 1880s, particularly the prints which had become popular in France in that period. The artist not only used oil paints but she also frequently worked with other media, notably pastels and intaglio. She was, too, very interested in engravings, a technique she had studied in Rome, and it was in these drypoints and coloured lithographs that she displayed the influence of Japanese art. Like her paintings, Cassatt's prints continue to show women at their daily tasks, but she uses broader areas of a single colour, outlines are bold, sweeping, and well-defined, and she ignores perspective. With Degas (who owned a printing press), Cassatt, Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), and Gustave Caillebotte (1848-94) together developed brand new colour printing techniques. This work influenced their later painting styles, but none seems to have hit on the idea that printing multiple and cheap copies of an artwork could be a sales opportunity.

Encouraging the Collectors

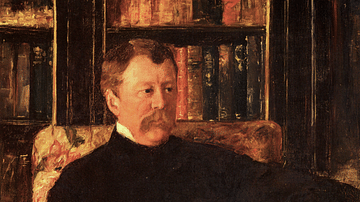

From the 1880s, international art dealers like Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922) began to exhibit the impressionists outside Europe, notably in New York. In America, this new art style received a more favourable response from the public and critics alike compared to their reception in Paris. Cassatt was influential on the success of impressionism in her home country. With her fine clothes and extravagant hats, Cassatt became a memorable bridge between buyers and painters. She encouraged her brother Alexander to build an art collection and her friend Henry Osborne Havemeyer, the immensely rich sugar refiner known as the 'Sugar King', and his wife Louisine (an old school friend of Mary's) to begin adding impressionists to their collection of Old Masters. Havemeyer followed Cassatt's advice and amassed a stellar collection, which now resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Another friend encouraged to collect was Bertha Palmer, who later bequeathed her paintings to the Art Institute of Chicago. One area where Cassatt did not help fine art in the United States was in competitions, for she refused to participate on juries despite receiving many invites to do so. She may have felt that serving on such selection panels would have compromised her artistic independence.

Death & Legacy

In 1891 she had a solo exhibition in Durand-Ruel's gallery in Paris. In 1893, Cassatt briefly returned to the United States to paint a large mural for the Women's pavilion at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. That same year, Durand-Ruel held a successful sales show in his gallery dedicated only to Cassatt and which was a much bigger affair than the show two years before. Cassatt did not need to earn a living from her art, but she must have been, in any case, pleased with the public success, and the money was turned into a useful property investment. From 1894, Cassatt made her home at Château de Beaufresne in Le Mesnil-Théribus in northern France. In 1895, Durand-Ruel organised another exhibition for Cassatt, this time in his New York gallery where 58 works were exhibited for sale.

Suffering from ill health and loss of vision in her later years, the artist had to give up painting around 1914. She spent time in Grasse in southern France during the war years (1914-18) and met up with Renoir there. Mary Cassatt died in Paris on 14 June 1926. She had never married or had children.

Cassatt had offered a unique view into family life in the 19th century, her work capturing scenes that male painters did not care to investigate. In addition, Cassatt was one of the few successful female painters in a period when it was considered unladylike to pursue a career in the arts. Her success helped open doors for other women artists, such as the decision by the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris to accept women from 1897.