Mary Prince (l. c. 1788 to c. 1833) was the first enslaved Black woman to publish an autobiography/slave narrative. Prince was illiterate but dictated her life story to the writer Susanna Strickland (l. 1803-1885), published in 1831 as The History of Mary Prince, which became a bestseller and garnered support for the abolitionist movement.

Prince was born a slave in Bermuda, taken to Antigua, and finally to England, where she left her master and found refuge in the Moravian Church (which opposed slavery). She was then taken under care by the abolitionist Thomas Pringle (l. 1789-1834), who was a friend of fellow abolitionist Susanna Strickland (better known by her married name, Susanna Moodie), who took down Prince's account.

Owing to the prevailing belief that Blacks were subhuman and incapable of writing, and because the work was put to paper by Strickland and edited by Pringle, it was dismissed by pro-slavery advocates as propaganda created by the Anti-Slavery Society. The details of her account, however, were corroborated by others who were acquainted with slavery as practiced in Bermuda and Antigua.

Even readers who knew nothing of daily life in those regions found Prince's story profoundly moving, and it went through three printings in its first year. England had outlawed the slave trade in 1807 but retained slavery, which was only ended by the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. How much influence Prince's autobiography had on Parliament passing that act is still debated, but judging by the work's popularity between 1831 and 1833, it quite likely played a significant role.

In her introduction to The History of Mary Prince: A West Indian Slave, scholar Sara Salih writes:

Telling her life story gave Prince and her supporters the opportunity to demonstrate that, contrary to contemporary belief, 'Negroes' were not merely chattels, but humans who were seriously damaged by the brutal treatment they were forced to suffer at the hands of their white masters and mistresses.

(8)

Prince's death date is unknown, but the last public record of her in England is 1833. Today, she is recognized as a national hero of Bermuda, and Mary Prince Day is celebrated annually on 2 August.

Slave Life & Freedom in England

Prince was born a slave in Devonshire Parish, Bermuda, c. 1788. Her father was an enslaved sawyer held by one David Trimmingham, and her mother was a domestic slave held by a Charles Myners. She had two sisters and three brothers, all belonging to Myners, and when he died, they were sold away from their mother to Captain George Darrell, who presented Prince to his granddaughter, Betsey Williams, who, as Prince says, treated her kindly as a pet.

When she was 12 years old, she was sold to Captain John Ingham while her two sisters were sold to another slaveholder. Ingham and his wife Mary regularly beat their slaves, killing Prince's friend, Hetty, who died after an especially severe whipping. Prince ran away from Ingham and took refuge with her mother, who was now the property of one Richard Darrell. Her mother hid her in a cave, but because she could be executed for harboring a fugitive, her father intervened and brought her back to the Ingham plantation.

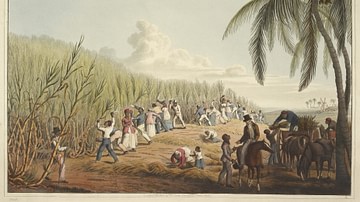

Ingham sent her to Grand Turk Island, where she was forced to work in the salt ponds, harvesting salt from the sea, and regularly standing in the water for 17-hour shifts, before she was bought by Robert Darrell and returned to Bermuda. Darrell put her to work on his farm before selling her to the merchant John Adams Wood Jr. in 1815.

Wood and his wife brought Prince to their farm in Antigua where she worked as a domestic. When the Woods were away on trips, Prince earned money selling coffee and yams and taking in washing, hoping to be able to buy her freedom. She also approached one Mr. Burchell, asking him to buy her, as the Woods were brutal masters who beat her often, but they refused to sell her and would not accept any amount she had made to purchase her freedom.

She joined the Moravian Church, where she began to learn to read, but to continue her studies, she would require a note from her master granting permission, which she knew he would not give, and so she never asked him. Soon after this, she met Daniel James, a free Black carpenter, and they were married in 1826. The Woods were outraged that she had married without their permission, and she was flogged with a horsewhip.

In 1828, the Woods took her with them to England, and she left their house one day, finding refuge at the Moravian Church in Hatton Garden, London. She was found there by Thomas Pringle, who hired her as a domestic and petitioned the Woods to free her, but they would not. Prince was only free as long as she remained in England, and so she could not return to Antigua and her husband without becoming enslaved again. Whether she ever saw Daniel James again is unknown, but unlikely.

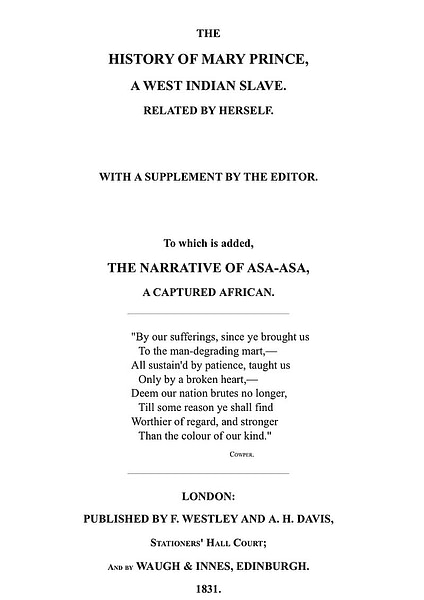

In 1830, while working for Pringle, Prince dictated her autobiography to Susanna Strickland. It was Prince's idea to publish her life story as she hoped it would influence lawmakers to abolish slavery. The History of Mary Prince was published, along with another slave narrative, The Narrative of Louis Asa-Asa, A Captured African, as a pamphlet in 1831, going through three printings in its first year.

Two libel cases arose from the publication, the second one brought by Wood, and Prince testified at both. Wood won his suit in 1833, the same year the Slavery Abolition Act was passed by Parliament, and this is the last time Mary Prince appears in the historical record.

Text

As noted, the influence of The History of Mary Prince on the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 is still debated, but the work significantly increased public support for abolition and the Anti-Slavery Society. Abolitionists had been publishing tracts and pamphlets for years arguing for an end to chattel slavery but, before Prince, did not have a firsthand account of what it was like to be a slave woman in the British colonies.

The History of Mary Prince also garnered support for abolition in the United States, appearing there shortly after David Walker's Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World (1829), among the most influential abolitionist works of the 19th century. Prince's work remained in print through abolitionist presses and remains as powerful a condemnation of racial slavery and racist attitudes today as when it was first published.

The following excerpt from The History of Mary Prince is taken from Documenting the South (https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/prince/prince.html), pp. 1-4. The site gives the work in full, and it appears below in the bibliography and External Links.

I WAS born at Brackish-Pond, in Bermuda, on a farm belonging to Mr. Charles Myners. My mother was a household slave; and my father, whose name was Prince, was a sawyer belonging to Mr. Trimmingham, a shipbuilder at Crow-Lane. When I was an infant, old Mr. Myners died, and there was a division of the slaves and other property among the family. I was bought along with my mother by old Captain Darrel, and given to his grandchild, little Miss Betsey Williams. Captain Williams, Mr. Darrel's son-in-law, was master of a vessel which traded to several places in America and the West Indies, and he was seldom at home long together.

Mrs. Williams was a kind-hearted good woman, and she treated all her slaves well. She had only one daughter, Miss Betsey, for whom I was purchased, and who was about my own age. I was made quite a pet of by Miss Betsey, and loved her very much. She used to lead me about by the hand and call me her little nigger. This was the happiest period of my life; for I was too young to understand rightly my condition as a slave, and too thoughtless and full of spirits to look forward to the days of toil and sorrow.

My mother was a household slave in the same family. I was under her own care, and my little brothers and sisters were my playfellows and companions. My mother had several fine children after she came to Mrs. Williams, –three girls and two boys. The tasks given out to us children were light, and we used to play together with Miss Betsey, with as much freedom almost as if she had been our sister.

My master, however, was a very harsh, selfish man; and we always dreaded his return from sea. His wife was herself much afraid of him; and, during his stay at home, seldom dared to shew her usual kindness to the slaves. He often left her, in the most distressed circumstances, to reside in other female society, at some place in the West Indies of which I have forgot the name. My poor mistress bore his ill-treatment with great patience, and all her slaves loved and pitied her. I was truly attached to her, and, next to my own mother, loved her better than any creature in the world. My obedience to her commands was cheerfully given: it sprung solely from the affection I felt for her, and not from fear of the power which the white people's law had given her over me.

I had scarcely reached my twelfth year when my mistress became too poor to keep so many of us at home; and she hired me out to Mrs. Pruden, a lady who lived about five miles off, in the adjoining parish, in a large house near the sea. I cried bitterly at parting with my dear mistress and Miss Betsey, and when I kissed my mother and brothers and sisters, I thought my young heart would break, it pained me so. But there was no help; I was forced to go. Good Mrs. Williams comforted me by saying that I should still be near the home I was about to quit and might come over and see her and my kindred whenever I could obtain leave of absence from Mrs. Pruden. A few hours after this I was taken to a strange house and found myself among strange people. This separation seemed a sore trial to me then; but oh! 'twas light, light to the trials I have since endured! –'twas nothing–nothing to be mentioned with them; but I was a child then, and it was according to my strength.

I knew that Mrs. Williams could no longer maintain me; that she was fain to part with me for my food and clothing; and I tried to submit myself to the change. My new mistress was a passionate woman; but yet she did not treat me very unkindly. I do not remember her striking me but once, and that was for going to see Mrs. Williams when I heard she was sick and staying longer than she had given me leave to do. All my employment at this time was nursing a sweet baby, little Master Daniel; and I grew so fond of my nursling that it was my greatest delight to walk out with him by the seashore, accompanied by his brother and sister, Miss Fanny and Master James. –Dear Miss Fanny! She was a sweet, kind young lady, and so fond of me that she wished me to learn all that she knew herself; and her method of teaching me was as follows:–Directly she had said her lessons to her grandmamma, she used to come running to me, and make me repeat them one by one after her; and in a few months I was able not only to say my letters but to spell many small words. But this happy state was not to last long. Those days were too pleasant to last. My heart always softens when I think of them.

At this time Mrs. Williams died. I was told suddenly of her death, and my grief was so great that, forgetting I had the baby in my arms, I ran away directly to my poor mistress's house; but reached it only in time to see the corpse carried out. Oh, that was a day of sorrow, –a heavy day! All the slaves cried. My mother cried and lamented her sore; and I (foolish creature!) vainly entreated them to bring my dear mistress back to life. I knew nothing rightly about death then, and it seemed a hard thing to bear. When I thought about my mistress I felt as if the world was all gone wrong; and for many days and weeks I could think of nothing else. I returned to Mrs. Pruden's; but my sorrow was too great to be comforted, for my own dear mistress was always in my mind. Whether in the house or abroad, my thoughts were always talking to me about her.

I stayed at Mrs. Pruden's about three months after this; I was then sent back to Mr. Williams to be sold. Oh, that was a sad, sad time! I recollect the day well. Mrs. Pruden came to me and said, "Mary, you will have to go home directly; your master is going to be married, and he means to sell you and two of your sisters to raise money for the wedding." Hearing this I burst out a crying, –though I was then far from being sensible of the full weight of my misfortune, or of the misery that waited for me. Besides, I did not like to leave Mrs. Pruden, and the dear baby, who had grown very fond of me. For some time, I could scarcely believe that Mrs. Pruden was in earnest, till I received orders for my immediate return. –Dear Miss Fanny! how she cried at parting with me, whilst I kissed and hugged the baby, thinking I should never see him again. I left Mrs. Pruden's, and walked home with a heart full of sorrow. The idea of being sold away from my mother and Miss Betsey was so frightful, that I dared not trust myself to think about it. We had been bought of Mr. Myners, as I have mentioned, by Miss Betsey's grandfather, and given to her, so that we were by right her property, and I never thought we should be separated or sold away from her.

When I reached the house, I went in directly to Miss Betsey. I found her in great distress; and she cried out as soon as she saw me, "Oh, Mary! my father is going to sell you all to raise money to marry that wicked woman. You are my slaves, and he has no right to sell you; but it is all to please her." She then told me that my mother was living with her father's sister at a house close by, and I went there to see her. It was a sorrowful meeting; and we lamented with a great and sore crying our unfortunate situation. "Here comes one of my poor picaninnies!" she said, the moment I came in, "one of the poor slave-brood who are to be sold to-morrow."

Oh dear! I cannot bear to think of that day, –it is too much. –It recalls the great grief that filled my heart, and the woeful thoughts that passed to and fro through my mind, whilst listening to the pitiful words of my poor mother, weeping for the loss of her children. I wish I could find words to tell you all I then felt and suffered. The great God above alone knows the thoughts of the poor slave's heart, and the bitter pains which follow such separations as these. All that we love taken away from us–Oh, it is sad, sad! and sore to be borne! –I got no sleep that night for thinking of the morrow; and dear Miss Betsey was scarcely less distressed. She could not bear to part with her old playmates, and she cried sore and would not be pacified.

The black morning at length came; it came too soon for my poor mother and us. Whilst she was putting on us the new osnaburgs in which we were to be sold, she said, in a sorrowful voice, (I shall never forget it!) "See, I am shrouding my poor children; what a task for a mother!"–She then called Miss Betsey to take leave of us. "I am going to carry my little chickens to market," (these were her very words.) "Take your last look of them: maybe you will see them no more." "Oh, my poor slaves! my own slaves!" said dear Miss Betsey, "you belong to me: and it grieves my heart to part with you."–Miss Betsey kissed us all, and, when she left us, my mother called the rest of the slaves to bid us goodbye. One of them, a woman named Moll, came with her infant in her arms. "Ay!" said my mother, seeing her turn away and look at her child with the tears in her eyes, "your turn will come next." The slaves could say nothing to comfort us; they could only weep and lament with us. When I left my dear little brothers and the house in which I had been brought up, I thought my heart would burst.