Mary Read, sometimes spelt Reade (b. c. 1690), was an infamous pirate during the Golden Age of Piracy (1690-1720) active in the Bahamas until her capture by the Jamaican authorities in 1720. As a crew member of the English pirate John Rackham, aka 'Calico Jack' (d. 1720), Read dressed as a man in battle and fought courageously in her last stand against the authorities while her fellow male pirates hid below decks.

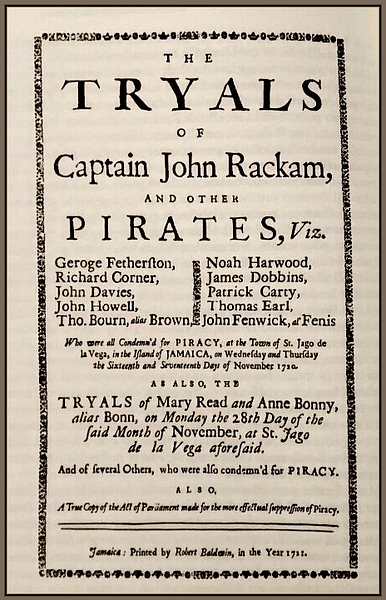

Read was one of only two female pirates of the so-called Golden Age who gained infamy, the other being her friend and crewmate Anne Bonny. Both were captured, tried, and sentenced to be hanged for piracy, but they had their executions delayed because they were each pregnant. While the fate of Bonny is not known, Read died in prison of fever in 1721.

Early Life

Details of Mary Read’s life before she turned to piracy are not known. However, this has not stopped writers from inventing a colourful if improbable biography. Read features in the celebrated pirate’s who’s who A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, compiled in the 1720s. The work was credited to a Captain Charles Johnson on its title page, but this is perhaps a pseudonym of Daniel Defoe (although scholars are still debating the issue). The work has been hugely influential on all later writers concerned with piracy in the Golden Age, even if it is an obvious but entertaining mix of fact and fiction.

The author of the General History did clearly have access to official papers, records of trials, and journalistic contemporary accounts, and many statements have proven to be factual when corroborated with historical records. However, there are also countless exaggerations and pure inventions such as private conversations and speeches seemingly repeated ad verbatim. It is perhaps significant that Defoe was both a successful journalist and author, in other words, he knew exactly how to blend fact and fiction for maximum literary effect. The presented life stories of Read and Bonny are incredible ones, with the author using the old literary trick of admitting as much and that, consequently, a reader may be forgiven for their scepticism but not total disbelief: "the odd incidents of their rambling lives are such, that some may be tempted to think the whole story no better than a novel or romance" (153).

According to some sources, Mary Read was born in Plymouth around 1690, although the account in the General History is based on Mary being born sometime earlier. According to Johnson/Defoe, Mary's mother had married a seaman, and they had a son. The father then disappeared, perhaps meeting his death in what was a dangerous occupation. Mary’s mother then fell pregnant to another man and, not being married, she left her home in London to have Mary born in secret. Mary’s elder brother died of illness in the meantime. Mary and her mother returned to London, and in order to persuade her mother-in-law to support her financially, Mary's mother dressed her daughter as a boy to make her late husband's relatives think their grandchild was still alive. The deception worked, and Mary’s mother received a crown each week by way of maintenance. Mary then continued the ruse when she was older in order to gain employment as a young footman. Apparently dissatisfied with this work, she next sought a life at sea, but as this was restricted to men only, she was again obliged to disguise herself. In this way, Read got a job as a servant on a British warship.

During the Nine Years’ War (1688-97) Read was back on land and fought in the army in Flanders against the French. She tried to become an officer but failed and so she left the infantry and joined a cavalry unit. During the conflict, which she fought in with some bravery, she fell in love with a fellow soldier, and they married. The pair entered civilian life and ran a public house called the Three Horse Shoes near Breda in the Netherlands. Mary then suffered two heavy blows to her happiness. First, her husband died prematurely, and then the public house faced ruin when the end of the war meant the soldiers moved on and Mary lost most of her clientele.

Mary decided to return to soldiering, but she was by now middle-aged, and in peacetime, there was not much hope of advancement. Presumably, too, her talent for disguise was by now being severely tested. Read next joined the crew of a ship headed for the Caribbean. She fell in love with a mariner on this ship who was challenged to a duel. Confident of her martial talents and keen to protect her lover, Read pre-empted this duel by insisting the challenger first face her. Read chopped down her assailant with her cutlass and shot him with a pistol or vice-versa but with the end result being the same: Read won the duel. Mary Read’s ship was then captured by pirates, and these she joined - the stark choice was often 'join or be killed'. This was perhaps around 1717. The fate of her male lover is not known as Read refused to name him at her trial.

‘Calico Jack’

The English pirate John Rackham, whose nickname was 'Calico Jack' because of his preference for plain cotton clothes rather than the often outlandish silks other pirates preferred, had met Anne Bonny on Providence Island (Nassau) in the Bahamas in the spring of 1719, and they became lovers. In August 1719, the pair captured the sloop William to pursue a life of piracy. On 5 September, Woodes Rogers (1679-1732), governor of the Bahamas, issued a warrant for the arrest of Rackham and his crew of around 20.

Rackham was a relatively small-time pirate compared to some of the other figures of the Golden Age of Piracy, and he is today really only known because of his association with Bonny and then Read. The latter joined Rackham’s crew after the capture of the ship she was sailing on or the joining together of two pirate crews, depending on the version of the story. In some accounts, Read and Bonny meet earlier on Providence Island.

To have two women pirates on board was unheard of. Many pirate captains created articles that strictly prohibited women and young boys on board their ships to avoid any squabbles over sexual favours or predatory behaviour. As the historian J. Rogozinski notes, in the case of Bonny and Read, "the pirates tolerated the women because they made themselves available to everyone in Rackham’s small crew" (33).

Both Read and Bonny wore men’s clothes at sea and are described as wearing handkerchiefs around their heads (which although now commonly thought to have been worn by most pirates, were actually rare, or at least undocumented amongst men). Testimony at their trials revealed that Bonny and Read only dressed as men when in battle when they usually fought with pistols. Indeed, the romantic suggestion often presented in popular pirate histories that they disguised themselves as men all of the time tests the imagination given the cramped life on board ships, even if there are historical cases of women sometimes fooling their peers on board merchant ships of the period.

The mixed pirate crew led by Rackham managed to evade the authorities, and they plundered the merchant ships in the waters around the Bahamas and a wide arc of shipping routes from Bermuda to Hispaniola, taking such unglamorous cargoes as tobacco and peppers. Bonny and Rackham had a child, but this was abandoned in Cuba where Bonny had spent the latter part of her pregnancy.

According to the General History, Anne Bonny attempted to seduce Read. Defoe/Johnson is clear that both women disguised themselves as men all of the time and so Bonny thought Read a rather pretty boy. At some point, Read reveals that she is a woman to Bonny and, to avoid his jealousy of the two women’s "friendship", also to Rackham. The rest of the crew are, rather improbably, left in the dark as to the sex of their two crewmates.

Read’s Capture

In October-November 1720, while anchored off the western tip of Jamaica, Rackham and crew suffered a surprise attack from the Tyger, sent by the new governor of the island, Sir Nicholas Lawes, and commanded by Jonathan Barnet. The pirates, numbering 18 according to Lawes' report to London, cut their anchor cable and made a hasty departure, but they were overhauled during the night and boarded. Rackham and the rest of the crew hid below decks - they were most likely all drunk - and only Read, Bonny, and one other man put up any resistance against Barnet’s men. They were, nevertheless, captured and taken to Spanish Town (at the time called St. Jago de la Vega) on Jamaica for trial.

Trial & Aftermath

The two women were to be tried separately from the men on 28 November, but both groups faced the same terrible charge: piracy. The documents from this trial reveal interesting points about the two female pirates’ past and their characters. Read and Bonny were described by one witness, Thomas Dillon, as "both profligate, cursing and swearing much, and very ready and willing to do anything on board" (Cordingly, 111). The witness Dorothy Thomas gave the following description of an attack, which confirmed beyond doubt that Read and Bonny were willing members of the pirate crew:

…the two women, prisoners at the bar, were then on board the said sloop, and wore mens jackets, and long trousers, and handkerchiefs about their heads; and that each of them had a machet and pistol in their hands, and cursed and swore at the men, to murder the deponents; and that they should kill her, to prevent her coming against them; and the deponent further said, that the reason of her knowing and believing them to be women then was by the largeness of their breasts.

(Cordingly, 64)

Another witness, this time a Frenchman speaking through an interpreter, confirmed the habit of Read and Bonny of changing their clothes for battle: "when they saw any vessel, gave chase, or attacked, they wore men’s clothes, and at other times, they wore women’s clothes" (Ibid).

All parties pleaded not guilty to the charges of piracy, despite the obvious evidence against them and the testimony of witnesses from not one but several ships they had plundered. No defence was given, and all were found guilty. Rackham was sentenced to be hanged and, as was customary, his dead body was hung in a cage to rot in the open air as a warning to others who fancied a life of piracy.

Anne Bonny and Mary Read were also sentenced to be hanged, but both women received a reprieve upon revealing to the court that each was pregnant. The laws at the time forbade the execution of a pregnant woman - the unborn child was innocent, if not the mother - and so Read and Bonny were temporarily allowed to live. Examinations were made of both women to ensure they were telling the truth. Read was recorded in the Parish Register for the district of St. Catherine as having died in a Jamaican prison of fever in 1721, she was buried on 28 April. The fate of Bonny is unknown, although a person of that name is noted in parish records as having died in Jamaica in December 1733.