The Mary Rose was a carrack warship built for the Royal Navy of Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547). The ship infamously sank in the Solent off the south coast of England on 19 July 1545, probably because water entered its open gun ports as it made a sharp turn. Almost all of the Mary Rose crew, up to 500 men, drowned. The wreck was raised in 1982, and is now preserved and on public display in the Portsmouth Historic Dockyard along with some 19,000 artefacts which give a unique insight into life in Tudor England.

The Royal Navy

Henry VIII was ambitious in his foreign policy, perhaps more so than he could actually afford. Attacking both Scotland and France several times in large land campaigns, Henry also decided to spend big on warships and so create the Royal Navy, one of his most significant contributions to England's history over the next few centuries. The king inherited a number of ships from his father, Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509), and was likely encouraged by such minor naval victories as during the Battle of the Spurs against the French on 16 August 1513. Further, a strong fleet would enable him to control the English Channel and blockade ports on Continental Europe if required. Henry's fleet was constructed in two spells, one prior to 1515, and another round of construction leading up to the 1540s. By the end of his reign, Henry would leave his heirs a navy boasting an impressive 53 ships, which now had a permanent fortified base at Portsmouth.

Carrack Design

Henry's fleet included the two great warships Mary Rose, built in Portsmouth and launched in 1511, and Henry Grâce à Dieu (aka 'Great Harry'), launched in 1514. The Mary Rose, with a keel length of 32 metres (105 ft) was assigned as Henry's vice-flagship while the latter never saw action despite its impressive size at 1,500 tons. The Mary Rose was originally 500-600 tons but after a refit was nearer 800 tons when it sank. In a long career, it served in the Battle of St Mathieu against the French in August 1512 and acted as a troopship in the Scottish campaign of 1513.

The Mary Rose was a carrack, a short and not particularly fast vessel which had forecastles for accommodation built high at the bow and stern. These forecastles were necessary for the large complement of marines on board as naval tactics still prioritised boarding as the best way to defeat an enemy ship. Carracks had only a 2:1 ratio of length-to-beam while their arrangement of masts and complement of 9-10 sails was as follows: "The fore and main masts had square main and topsails while the mizzen and, when fitted, the fourth (bonaventure) masts were lateen rigged." (Bicheno, 337). Although stable in heavy seas and capable of carrying a large quantity of cargo, the carrack's width and superstructures made them top-heavy and unwieldy during sharp manoeuvres. The relative lack of manoeuvrability of this class of ship was considered an acceptable risk, given that the Royal Navy's function was to protect England's shores and not to sail the High Seas as in later periods.

Previously, ships carried many small cannons, which were used to blast soldiers from the deck of an enemy vessel with scattered shot. Gradually, though, larger cannons were being employed which were capable of sinking an enemy ship by blasting holes in their hulls below or near the waterline. As these larger cannons were too heavy to place in the forecastles, where they would seriously unbalance the ship, they had to be placed lower in the hull, necessitating the use of gun ports - in effect windows which could be closed with a shutter when not in battle. On the Mary Rose, the gun ports would have been only about one metre (39 inches) above the waterline. Smaller cannons were still carried in the forecastles, especially at the stern, as these could be used to fire down on the lower middle deck of an enemy ship.

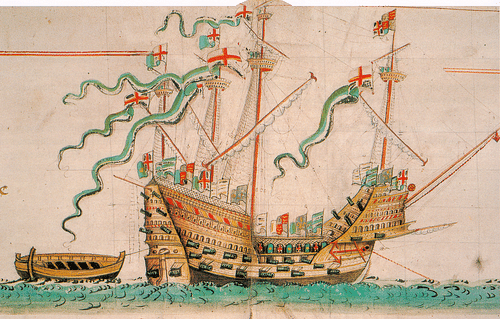

The Mary Rose was, therefore, refitted out along these lines. Originally, its hull was clinker-built (with overlapping planks) but was refitted with a smooth carvel hull around 1535. Gun ports were added along the length of the hull so that the ship boasted over 90 cannons. This new-look Mary Rose is the version famously portrayed on the Anthony Roll. These three rolls of vellum, now in the British Library in London, carried illustrations of 58 English ships and, created by Anthony Anthony, they were presented to Henry VIII sometime in the early 1540s. The illustrations are not always entirely accurate but they do give a good impression of the Mary Rose at its best.

Sinking

During the Anglo-French war of 1542-46, Francis I of France (r. 1515-1547) sent a 120-200 ship naval fleet commanded by Admiral Claude d'Annebault to cross the English Channel and attack the Isle of Wight and probably Southampton. When faced with this force on 16 July 1545, an English fleet of around 80 ships retreated back towards Portsmouth. The wind then dropped unexpectedly and four French ships rowed themselves into position and surprised the becalmed English fleet on 19 July.

The Mary Rose and the Henry Gråce à Dieu rolled out their cannons and attempted to face off with the speedier French galleys in the Solent, the strait between the Isle of Wight and the coast of England. The Mary Rose would have boasted a full complement of men: around 200 seamen, 185 marines, 30 gunners, and a good number of archers (138 longbows were discovered in the wreck). According to eyewitness accounts, the Mary Rose fired a broadside at the enemy, but then disaster struck as the English carrack heeled over to starboard. The Mary Rose then sank swiftly as the king looked on from his position on the shore at Southsea Castle. Lost with it were 400-500 men, including the vice-admiral, Sir George Carew (b. c. 1504). Perhaps as few as 25 men escaped with their lives. Not only could few seamen actually swim but nets had been placed over the Mary Rose's deck to inhibit French borders. These nets became a deadly trap for all those on board.

In the aftermath of the sinking, a French force then landed on the Isle of Wight but was successfully beaten back to their ships. Riddled with disease, the French fleet was eventually obliged to return home. As a consequence of the enormous financial loss and the further expenses which continuing the war with France would bring, Henry and the Privy Council decided to change strategy and secretly negotiate an alliance with either France or Spain. In the end, a peace deal was signed with France in June 1546. The Mary Rose was not forgotten and several attempts were made to salvage her in the late 1540s. The ship, though, had sunk deep into the soft muddy seabed of the Solent where it would remain for the next 437 years.

Theories on the Causes of the Sinking

There have been many theories discussed as to exactly why the Mary Rose sank, despite the number of eyewitnesses stating it keeled over of its own accord while turning and then quickly sank. The most likely explanation for the catastrophe is that the ship had made too tight a turn - perhaps trying to avoid running aground - and that, top-heavy in its design, the ship had so inclined that water flooded into the hold via the open gun ports. That the gun ports were open when the ship sank is attested by the wreck itself. Further, the wind direction on the day of the sinking may have further pushed the ship over to one side and exposed the gun ports to the sea.

Naturally, the French were eager to claim credit for sinking Henry's pride and joy. Intriguingly, a French cannonball made of granite was discovered in the hull, a fact some historians have used to support the theory that the ship was sunk by cannon fire. Others state that the granite might have come from Britain and been a part of the ship's ballast. Even if it had been holed by a cannon shot, the water rushing in would likely not have sunk the ship alone. However, water entering the hold and then destabilising the ship may well have then caused it to lean and let in much more water through the gun ports on one side of the ship, thus explaining the speed of the vessel's demise.

In yet another theory, scientific examination of the teeth of 18 crew members has revealed that 60% were likely not English. Could this mean the foreign members of the crew had not understood orders to close the gun ports in time? As ever, in the confusion of battle, it was perhaps a combination of several of these factors which brought about the ship's demise. Certainly, only a unique series of events would explain why the Mary Rose had never had flooding problems in its previous years of service.

Recovery Operation

The Mary Rose, leaning 60 degrees to starboard and settled in the seabed, was discovered again in 1836 by two divers, John and Charles Deane. The two brothers had noticed a few beams protruding from the seabed, and they found several cannons, too. Forgotten again for another 150 years, the area was then explored from 1965 by amateur divers in a project to find wrecks in the Solent. The team, led by Alexander McKee, came across an unusual depression in the seabed in 1966, and a sonar scan in 1967 revealed there were indeed solid remains beneath the depression. In May 1971, excavation work began, the site was surveyed, and several larger artefacts brought to the surface. Over the next ten years, a volunteer team of 600 divers made 28,000 dives to the site, recovering over 19,000 artefacts.

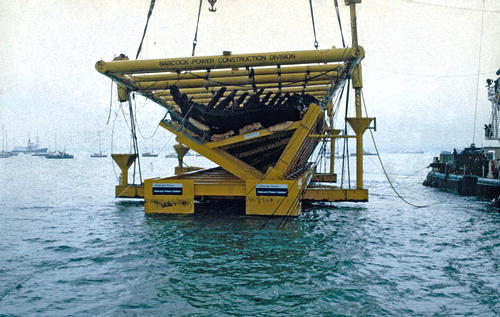

The starboard side of the Mary Rose was still intact, making a complete extraction back to the surface possible. Despite the wreck having been damaged by both time and the 19th-century attempt to dislodge what had become a hazard to shipping, the aireless muddy seabed had preserved much of the wood which would otherwise have long since disappeared. The Mary Rose wreck was thus salvaged in June 1982. A special steel frame with multiple airbags was built to carefully cradle the wreck as it finally returned to the surface where it was placed on a barge and taken to Portsmouth's Royal Naval Base. The whole delicate process was broadcast live on television as 60 million people watched what was one of the great archaeological success stories of the century.

Artefacts

The immediate problem was to preserve wood and leather items which, now exposed to air again, were in danger of quickly disintegrating. The hull was subjected to a continuous chemical spray to conserve its condition and was put on public display in 1983. Today, the wreck and its artefacts are managed by the Mary Rose Trust (maryrose.org).

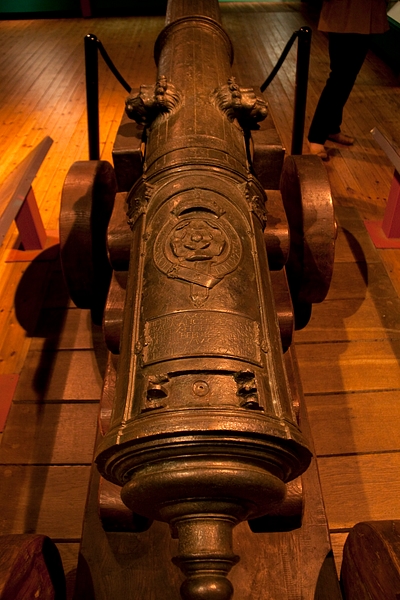

Many of Mary Rose's cast iron and bronze cannons were recovered, including examples weighing up to 25 tons and decorated with the Tudor rose or lion's heads. Other weapons included the 138 longbows mentioned above and 3,500 arrows. There were, too, a number of gunpowder handguns, swords, daggers, and pikes.

Other finds include many wooden pieces of the ship's rigging such as pulleys and sheave blocks. The huge brick galley oven (one of a pair) was recovered, as well as large cooking pots, over 50 sea chests used by crew members for their personal possessions, three compasses, nine handheld sundials, carpentry tools, medical equipment and even the ship's bell (cast in 1510 as indicated by the inscription). A grindstone and heddle frame for making rope repairs was another unique find.

At a more personal level, several wooden combs and metal scissors used by the crew survive, as do pewter plates, tankards, and spoons. The latter would have belonged to the ship's officers, and a number of examples even have the initials 'G.C.' and so were owned by the fleet commander, Sir George Carew himself. Ordinary crew members used wooden plates and mugs, some of which have survived.

Life on board a Tudor ship is further revealed by such artefacts as drums, a backgammon board, bone dice, leather book covers, musical pipes, and gold coins. In a stark reminder that the wreck of the Mary Rose was a grave, the skeletons of around 200 men were discovered, along with items of clothing such as hats, jerkins, and over 250 shoes made of leather. Finally, the wreck contained a skeleton of a young male dog who would have been kept to catch rats on board but who may also have acted as the lucky mascot on this most ill-fated of ships.