Mary of Guise (aka Marie de Lorraine, 1515-1560) was a French noblewoman who became the second wife of James V of Scotland (r. 1513-1542). With the premature death of her husband, her daughter Mary, Queen of Scots (r. 1542-1567) became queen. Mary was still a minor and so Mary of Guise acted as her regent from 1554 to 1560. A staunch Catholic and supporter of French interests in Britain, Mary was not always popular with more traditional-minded Scottish nobles and Protestant leaders like John Knox (c. 1514-1572 CE). Mary’s daughter did eventually become queen in her own right, and her grandson, James I of England, went on to unify the thrones of Scotland and England from 1603.

Early Life

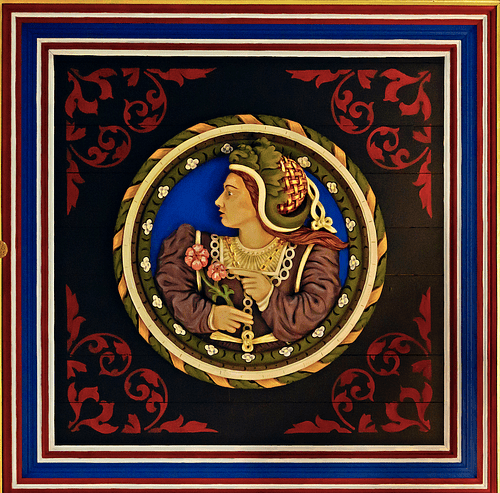

Mary of Guise was born on 22 November 1515 in Bar-le-Duc, Lorraine, France. She was born into the powerful and most prominent Catholic family in France. Mary was the eldest daughter of her father Claude, Duke of Guise, and her mother Antoinette de Bourbon. Mary is described as having a striking figure with good looks, an unusual height, and red-gold hair. Her personal emblem was the phoenix, an indication of her strong and ambitious character.

On 4 August 1534, Mary married Louis II d’Orléans, Duke of Longueville, and the couple had two sons, François and Louis (only the former lived to inherit his father’s dukedom). Louis II died in June 1537, and Mary’s destiny now lay abroad. The French king, Francis I of France (r. 1515-1547), wished to seal the 'Auld Alliance' between his kingdom and Scotland and so he arranged for Mary, still only 21, to marry the king of Scotland. Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547) had been another possibility, but that monarch’s record with his first two wives was hardly likely to instil confidence in Mary or Francis I.

Queen Consort: James V of Scotland

James V of Scotland had married Madeleine de Valois (1521-1537), daughter of Francis I of France, on 1 January 1537 CE in Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, but, always having had frail health, Madeleine died of consumption six months later. On 12 June 1538, James married Mary of Guise, presumably, the two had met while James had stayed in France for seven months in 1536-1537. Mary was actually a cousin of James’ through the Gueldres line, but more importantly, she brought with her a handsome dowry. The Scottish king was known to have had many mistresses and fathered at least nine illegitimate children, but he needed, above all, a legitimate heir. Such was the necessity for this, Mary was not given a coronation until she was pregnant,an event held at Holyrood Abbey. Both their first two children - both males - died in 1541, but Mary of Guise did produce one daughter, Mary Stuart, born on 8 December 1542 at Linlithgow Palace, Lothian.

Mary influenced her husband to take a stance against Lutheran Protestants, a decision which blackened the reputations of the royal couple when later Protestant writers drew up their histories of Scotland. The king was unpopular in his own lifetime, too, because of his heavy taxes, high spending on lavish refurbishments for his castles, and, at least for some, his too-close-for-comfort relations with France. Stirling Castle was a particular beneficiary of the king’s attention, and today the Queen’s chambers have been faithfully restored to how they would have looked when Mary of Guise resided there.

King James died on 14 December 1542 of a lingering 'fever' (perhaps cholera or dysentery). This disaster came one month after military defeat to an English army at the Battle of Solway Moss. James had left no male heirs and as a result, his infant daughter Mary, who was only six days old, inherited the throne, when she became known as Mary, Queen of Scots. Young Mary was crowned on 9 September 1543 in Stirling Castle, and her regent, selected by the Scottish Parliament, was James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, a great-grandson of James II of Scotland (r. 1437-1460). Mary of Guise replaced Arran in April 1554 and became her daughter’s regent with James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell (c. 1535-1578), a loyal and powerful ally. A further practical aid to Mary was the arrival of 700 French troops, distributed to several key castles across the kingdom. However, these did not come cheap, and the regent was obliged to sell off some of her plate and even personal jewellery to pay for them.

The Regency: War with England

Henry VIII, like his predecessors, was ambitious to control Scotland. The English king’s initial plan was to use diplomacy and have his son Edward, the Prince of Wales, marry the young queen Mary. Mary of Guise was not against the idea, but the Scottish lords were not keen to forgo any of their independence, and the Scottish Parliament rejected the offer. Henry persisted with the scheme with the so-called 'Rough Wooing' of 1544-1545 CE when the Scottish Lowlands were ravaged and Edinburgh attacked in 1544. Unsurprisingly, this policy only hardened Scottish resolve, and the Scots were victorious against an English army at the Battle of Ancrum Moore in 1545. Henry abandoned his plans until another army was sent in 1547, which won the Battle of Pinkie (near Musselburgh) on 10 September. This campaign was during the reign of Henry’s successor Edward VI of England (r. 1547-1553), but no lasting advantage was achieved, and the newly established English garrisons there came under repeated Scottish attack. England was then also having problems with its own internal rebellions and defending its interests in France. In 1550 CE, a peace treaty was signed between England, France, and Scotland.

In early 1548 CE, Mary of Guise had sent her daughter to be looked after by her French family and educated at the court of Henry II of France (r. 1547-1549 CE). Mary of Guise herself spent 1550-1551 in France with her relatives before returning to Scotland. The Treaty of Haddington was signed, which arranged for Queen Mary to marry the future Francis II of France (r. 1559-1560). The marriage took place in April 1558 and so Queen Mary became the queen of France (r. 1559-1560) as well as Scotland.

Deposed as Regent

Meanwhile, Elizabeth I of England had begun her reign in 1558 (she would rule until 1603). Protestant Elizabeth even sent aid to the Protestant Lords of the Congregation in Scotland to destabilise the throne, which then led to Mary of Guise being deposed as regent, or 'suspended' as Mary’s enemies preferred to put it in October 1559.

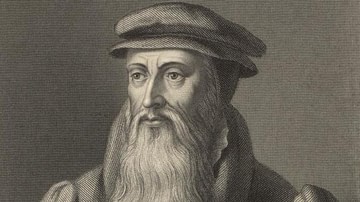

Mary’s downfall had perhaps been her too forceful support of Catholicism and her promotion of ties with France, a situation which was perhaps a result of pressure from the French king. Both of these policies diminished Scotland’s independence in the eyes of many nobles. Scottish nationalist barons resented the number of French officials at the royal court. There had also been the worrying annexation of the Duchy of Brittany by the French Crown in 1532, and the Scots did not wish to see the same fate befall them. There had even been a revolt in May 1559, led by the firebrand Calvinist minister John Knox. Knox boldly promised Mary that any threat, legal or otherwise, to Protestants in Scotland would oblige them "to take the sword of just defence" (Brigden, 218). Knox was a vociferous opponent of women as rulers, and Mary of Guise in particular, as expressed in his First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women (1558). Knox’s misogynistic position, though, was far from helpful to his own cause considering his main ally against Catholicism was Queen Elizabeth I of England.

Mary was not so easily removed from Scottish politics, however. With French military support, she managed to take control of Edinburgh Castle. Scotland, though, had become a pawn in a wider European game of thrones, and Elizabeth I responded to French interference by sending an English fleet to blockade the east coast of Scotland and a land army to besiege Leith in April 1560.

Death

Forces loyal to Mary of Guise had managed to withstand the English assault at Leith with success, but their cause there and across Scotland was dealt, literally, a fatal blow. Mary died of illness - likely dropsy (oedema) - at Edinburgh Castle on 11 June 1560; she was buried in Rheims in her French homeland in March 1561. With her death and the loss of a French fleet in a storm at sea on its way to assist the dowager-regent, the Catholic cause in Scotland was finished. The combined anti-Catholic/Mary/French cause had won. The Treaty of Edinburgh enforced the removal of all French troops from Scotland, and in July 1560, a Protestant Regency Council was established to rule the kingdom.

Back in France and following Francis II’s premature death in December 1560, Queen Mary decided to finally return to Scotland and claim her birthright in person. However, Mary, Queen of Scots’ Catholic beliefs, two marriages, and several murderous intrigues did nothing for her popularity. Ultimately, Queen Mary was obliged to abdicate in July 1567. Queen Mary even attempted to wrest the English throne from her cousin Queen Elizabeth but was ultimately executed for her troubles in 1587, having fled Scotland in 1568. Mary of Guise’s grandson had become James VI of Scotland (r. 1567-1625) following his mother Mary’s abdication. Then, when Elizabeth I of England died without an heir, James VI was invited to become the king of England as James I (r. 1603-1625) and so the Stuart line managed to join the two crowns, a unification that centuries of warfare had failed to achieve.