The Maori people of Aotearoa (New Zealand) have long observed the heliacal (pre-dawn) rising of the star cluster commonly known throughout the world as Pleiades or Messier 45 (M45), located in the constellation of Taurus. Matariki is the Maori word for this group of seven stars, which are an important astronomical feature and source of cosmic knowledge for Maori.

Pleiades is visible for most of the year in the night sky but dips below the western horizon during the early evening of May. The pre-dawn appearance of Matariki from the northeastern horizon at the beginning of the winter months (June and July) signified the beginning of the Maori New Year, celebrated by singing, dancing, and acknowledging Matariki’s deep connection to harvesting, celebration of life, and the honouring of tupuna (ancestors). Matariki coincided with the end of the harvest season when pātaka (food storehouses) were full, and there was more time to spend with whanau (family).

The last heliacal rising of Matariki during Pipiri (June) was especially significant as Maori believed that the spirits or life force (wairua) of those who had died would journey along Te Ara Wairua (pathway of the spirits), descend into the underworld and the endless night. Pohutukawa, one of the stars of the Matariki cluster, was connected to the dead, and whanau would farewell loved ones by calling out the names of the deceased as Matariki rose in the early morning sky.

Tohunga kokorangi (astronomy experts) would observe the visibility, shape, and colour of each star in the Matariki cluster and make predictions about the coming year for their iwi (tribe). For example, if the stars were hazy and appeared close together, a cold winter was forecast, and the planting of kumara (sweet potato) would be delayed until October. Expert Maori navigators on voyaging waka (canoe) would use Matariki as a celestial guidance system in their journey across the Pacific.

Not all iwi celebrate Matariki at the same time, but it is a period of renewal and reflection, as well as an opportunity to learn from the successes and failures of the past year. Traditionally, a pūtātara (shell trumpet) was used to signal the start of Matariki, and pākau (kites) would be flown as they were thought to touch to the sky.

Pleiades in the Ancient World

Pleiades has long held the imagination of people throughout the world, possibly because it is one of the nearest star clusters to Earth (440 light-years) and can be seen by the unaided eye. The Pleiades stars are considered 'sibling stars,' born from the same dust cloud around 100 million years ago.

Pleiades has served as an agricultural and maritime calendar for many civilisations, as well as being a time marker. The name is thought to have derived from the ancient Greek word plein, meaning "to sail", although another version of the name is spelt 'Peleiades', meaning a "flock of doves". For the Greeks, Pleiades signalled a return to sailing the Mediterranean. The 20,000-year-old Palaeolithic drawings in the Lascaux Caves in France are thought to represent Pleiades.

The entire star cluster contains over 1000 stars, although only six to nine are visible to the naked eye, depending on the observer's eyesight. Classical antiquity considered the number seven to be mystical and auspicious, so Pleiades was called the Seven Sisters, Seven Maidens, or Seven Little Girls. The ancient Greeks referred to Pleiades as the seven daughters of Atlas and Pleione (protectress of sailing), while the Australian Aboriginals believe they are seven women being pursued by mythological men.

A Bronze Age artifact, the Nebra Sky Disk, dating to 1600 BCE, was found in the Ziegelroda Forest in Germany. A cluster of seven dots at the top right of the disk has been interpreted as the Pleiades constellation.

In North America, the Cherokee believed they descended from Pleiades and came to Earth as star seeds, which is a reference to the name the Zuni people of modern-day New Mexico gave to the cluster of stars – The Seed Stars. For many cultures worldwide, 'seed stars' is a fitting name as the seed-planting season is associated with the cluster’s disappearance in spring in the northern hemisphere.

The Japanese name for Pleiades is Subaru, which means "gathering" or "coming together". The logo for Subaru, the Japanese car manufacturer, incorporates six stars. One of the earliest astronomical references to Pleiades in Chinese literature dates to 2357 BCE, and the glittering cluster was called blossom or flower stars.

Although Pleiades has been known by different names throughout history, ancient cultures and mythologies associated with the small dipper-shaped arrangement of stars shared certain themes: changing seasons, renewal and death, planting, and harvesting.

Matariki in the Pacific

Starlore in the pre-European Pacific referred to Pleiades by several names that share a similarity in language: Matali'i (Samoa), Matari'i (Tahiti), Makali'i (Hawaii), Mata-ariki (Tuamotu archipelago), and Matariki (Rapa Nui, Rarotonga, and Aotearoa).

Matariki has been translated as "little eyes" or "small eyes", although Maori translate it as the "eyes of the god", an abbreviation of Ngā Mata o te Ariki. According to one legend, the god being referred to is Tāwhirimātea, god of the winds and weather. He became distraught when his parents, Ranginui (sky father) and Papatūānuku (earth mother), were forcibly separated by their other children, and Ranginui was sent to the skies. Tāwhirimātea gouged out his eyes and hurled them into the heavens as a sign of his aroha (love) for his father, where they stuck to Ranginui’s chest, forming Matariki. Te Tautari-nui-o-Matariki is another name for the star cluster and means "Matariki fixed in the heavens".

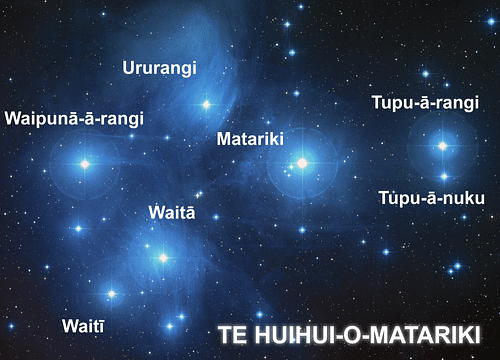

For some iwi, Matariki is a seven-star cluster containing a mother (whaea), surrounded by her six daughters with the following star names: Tupu-ā-nuku, Tupu-ā-rangi, Waipunarangi, Waitī, and her twin, Waitā, and Ururangi. Maori astronomer, Dr. Rangi Mātāmua, suggests that two stars have been lost to indigenous knowledge - Pōhutukawa and Hiwaiterangi – making Matariki a nine-star group. According to this whakapapa (genealogy), each star has a defined purpose that is connected to the Maori belief that Matariki watches over well-being, abundant harvests, and life and death:

- Matariki (the mother) is the individual star Alcyone and is referred to as kai whakahaere or the ‘gatherer’, encouraging people to reflect on the past.

- Pōhutukawa (Sterope/Asterope) is the star that carries the spirits of those who have died since the last heliacal rising of Matariki, connecting the living to those who have passed. Pōhutukawa gave rise to the saying ‘kua wheturangihia koe’ (you have now become a star).

- Tupuānuku (Pleione) is the eldest of Matariki’s daughters and encourages the cultivation of kai, rongoā, and kākahu (food, medicine, and clothing).

- Tupuārangi (Atlas) is linked to birds and food from trees, such as fruit and berries. Kererū (bush pigeon) were caught, cooked, and preserved in their fat as Matariki rose in the early morning. Tupuārangi would learn the songs of native birds, and her purpose was to encourage the sharing of gifts with others.

- Waitī (Maia) is connected to fresh water and food that comes from rivers, streams, and lakes.

- Waitā (Taygeta) is associated with the ocean. The twins, Waitī and Waitā, remind us to appreciate water sources and their environment.

- Waipunarangi (Electra). The name of this star can be translated as "water that pools in the sky" and links the star cluster to rain.

- Ururangi (Merope) determines the nature of winds.

- Hiwaiterangi/Hiwa (Celaeno) is the youngest star in the cluster and is the wishing star. Maori would request that Hiwa bring an abundant harvest or that hopes and dreams would be realised.

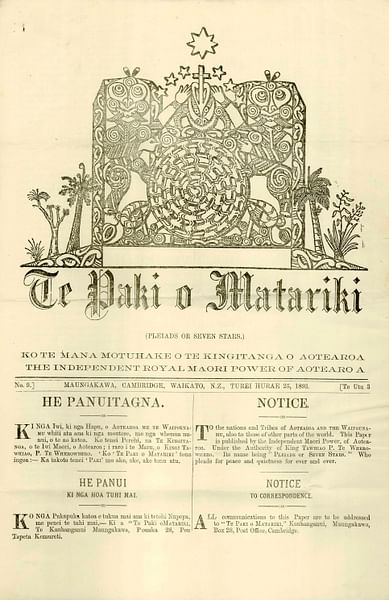

There were early attempts by Pākehā (European) settlers to record Maori starlore. The 19th-century ethnographer, Elsdon Best (1856-1931), compiled a comprehensive record in his book, The Astronomical Knowledge of the Maori (1922), which showed that ancestral knowledge of the cosmos was an integral part of Maori life. Three notable explorers to New Zealand recorded and published detailed accounts of Maori life and culture but failed to include Maori astronomy: Captain James Cook (1728-1779), Jean-François-Marie de Surville (1717-1770), a French East India Company merchant captain, and French explorer Marion du Fresne (1724-1772), who arrived in the Bay of Islands (North Island) in 1772 and was killed by Maori, all had astronomers on board, who carried out their own astronomical observations. Indigenous celestial lore was, however, closely guarded knowledge taught only to a select few in the whare kōkōrangi (astronomical house of learning).

By the late 19th century, European settlement, war, and land alienation, as well as the ravages of disease, meant that traditional Maori astronomical practices and celebrating Matariki had largely disappeared.

Matariki & Kumara

Matariki has a deep association with growing, harvesting, storing, and gifting of food and was viewed by Maori as a provider of food for the coming year. The appearance and grouping of the star cluster during Pipiri (June) was interpreted by tohunga kokorangi, who would then predict the timing for planting, especially of kumara (sweet potato). If a favourable interpretation, planting of kumara would begin in September. Matariki is sometimes referred to as ‘Hoko kumara'.

Kumara is a taonga (treasure) and a highly prestigious crop for Maori, whose Polynesian ancestors brought the vegetable with them when they arrived in New Zealand c. 1320-1350. Offerings from the first kumara crop would be given to Matariki, and when the star cluster was high in the night sky, food would be hung in nearby trees to encourage the growth of kumara throughout koanga (spring) and into raumati (summer).

Maori followed a lunar calendar (maramataka), which has twelve, 29.5-day months and a 354-day year. It was believed the phases of the moon, as well as whetū (stars), also influenced food growth, and Mawharu, which is the twelfth day after the new moon, was viewed as a favourable time to plant kumara.

Matariki’s Modern Revival

Throughout the 20th century, many Maori cultural and astronomical practices diminished, mainly because much of it was handed down through oral histories, and the celebration of Matariki disappeared.

A Matariki revival happened in the late 1990s with several festivals planned and attended by thousands who flew pākau (traditional kites named for a bird's wing). Although there is no single day that marks Matariki and some iwi look to Puanga (Rigel in the constellation Orion) as the signal to start the new year, widespread interest has led to the first Matariki public holiday, which will be held on Friday, June 24, 2022 – a unifying occasion in recognition of Aotearoa’s indigenous history and the country’s shared identity.

![Matariki [Nga mata o te ariki, o Tawhirimatea: The eyes of the god, Tawhirimatea]](/uploads/kraked/6/6-2578_ci_preview.jpg?v=1623642962-1744628777)