Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (1758-1794) was a French lawyer who became one of the primary leaders of the French Revolution (1789-1799). From his initial rise to stardom in the Jacobin Club, Robespierre went on to dominate the powerful Committee of Public Safety and oversee the Reign of Terror. He was overthrown and guillotined on 28 July 1794.

Beginning in May 1789, Robespierre's political career was brief yet impactful. He championed the will of the people with such a degree of conviction that he became known as the "Incorruptible"; a contemporary once mused that Robespierre was the type to pay a man to offer him a bribe so he could make a show of declining it. His strict adherence to his principles was drawn from a perceived mandate from the people. Robespierre considered himself to be the people's spokesman, which meant that those who opposed him necessarily opposed the people. Such would be his rise and his downfall.

For better or worse, some have considered him to be the French Revolution personified, a notion believed by Robespierre himself and mentioned by historian Patrice Gueniffey who writes, "none of [the other revolutionaries] wedded his era as Robespierre did, none merged with it to the point where his death became the conclusion of countless histories of the Revolution" (Furet, 298). Indeed, it was with this impassioned self-confidence that Robespierre led France during the bloody days of the Terror, marking him as one of the Revolution's best-known and most divisive figures.

Pre-revolutionary Life

Robespierre was born on 6 May 1758 in Arras, a small city in the French province of Artois. He had been conceived out of wedlock, and his parents had hurriedly married to avoid the shame of an illegitimate child. His father, also named Maximilien de Robespierre, was a wayward lawyer with a reckless disposition, and his mother, Jacqueline-Marguerite Carrault, was a brewer's daughter. Young Maximilien's birth was followed by three more Robespierre children: girls Charlotte (1760-1834) and Henriette (1761-1780), and another boy, Augustin (1763-1794). In 1764, Jacqueline died at age 29 while giving birth to a stillborn daughter; her death devastated the elder Robespierre who could not bear to remain in Arras any longer. He left for good in 1767, abandoning his children to the care of relatives. According to the memoirs of Charlotte Robespierre, the loss of their parents forced young Maximilien to grow up quickly to care for his younger siblings. Once a typical, carefree child, he became serious, solitary, and somewhat aloof.

In 1769, Maximilien won a scholarship to the prestigious college Louis-le-Grand in Paris. He did quite well, developing a fondness for rhetoric and ancient history and becoming close friends with fellow student and future revolutionary Camille Desmoulins (1760-1794). It was at Louis-le-Grand where Robespierre was likely first acquainted with the works of Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau's ideas strongly informed Robespierre's political development and would greatly influence his controversial revolutionary career. Particularly, Robespierre latched onto the idea that government is derived from the general will of the people, as well as the concept of patriotic virtue, which stipulated that a citizen must put the good of society above his own selfish desires.

After graduating Louis-le-Grand, Robespierre studied law at Sorbonne University for three years. In 1781, he was accepted to the bar and returned to Arras to set up a practice. For the next eight years, he worked to establish himself in his profession, rooming with his sister Charlotte to save money. He rarely lost a case, partially because he never accepted a case unless the defendant was the victim of obvious injustice. In 1782, this success led to his appointment to the criminal court of Arras. In 1783, he won a famous and bizarre case involving the defendant's right to put a lightning rod on his own roof; Robespierre's arguments were viewed as a symbolic defense of science and enlightened reason against superstition.

Alongside his legal career, he wrote essays in favor of equality before the law, one of which earned him a prize from the Academy of Metz in 1784. By 1789, he had built a reputation as one of Artois' foremost defenders of justice. So, when it was announced that King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) had summoned an Estates-General to discuss France's failing finances, Robespierre was well-known enough to be elected as one of Arras's representatives to the Third Estate, the class of the commoners.

The Revolution Begins

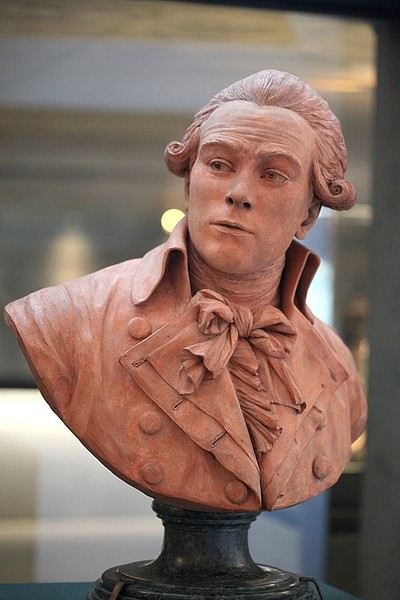

Robespierre arrived in Versailles an obscure, small-city lawyer, unaware of the mark he was to make on history. Barely 31 years old, the Robespierre of 1789 was an unimposing figure with frail, pale green eyes, a receding hairline, a soft voice, and a face that had almost feline features. His meticulously powdered wig and fine clothes hinted at a discomfort with disorder, while his simple manners caused some to think him timid and others to view him as suspicious. Although Robespierre did not dominate the revolutionary stage when the curtains first opened on 5 May 1789, he maintained a strong supporting presence, giving his first notable speech in early June; he would go on to deliver an estimated 900 speeches over the course of the next five years.

In Versailles, as in Arras, he quickly cultivated a reputation as an "upholder of the wretched, avenger of the innocents" (Furet, 299). He spoke often in defense of the marginalized, namely Protestants, Jews, and slaves. He supported the union of the three estates on 17 June into one National Constituent Assembly and applauded the expression of the people's will on 5 October, when the Women's March on Versailles dragged the king to Paris. Gradually, Robespierre's name began popping up in newspapers and he became known for his strong convictions; Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau once said of him: "that man will go far: he believes everything he says" (Furet, 304). It was this sentiment that led Robespierre to be known as "the Incorruptible" by 1790.

Jacobin Leader

His speeches were not always taken seriously by his colleagues in the Assembly; he was kept out of the committees and was never elected to the Assembly's presidency. This did not matter to Robespierre; his target audience was not his fellow deputies, but the galleries, where the people of Paris gathered to watch the proceedings. Gaining popularity with the people, Robespierre also made waves in the Jacobin Club, a political society where revolutionaries gathered to discuss goals and agendas. Here, he sparred with titanic orators like Mirabeau and Antoine Barnave, riling up the Jacobins with his radical speeches fighting for universal suffrage, unrestricted access to public offices, and the right to petition. He became popular enough to be elected president of the Jacobins on 31 March 1790, and his influence in the club only increased over time; novelist Jean-Baptiste Louvet would later describe Robespierre's effect on his radical Jacobin audience: "it was no longer applause, but convulsive stamping. It was a religious enthusiasm, a holy furor" (Furet, 304).

In June 1791, the king's failed escape attempt from France, known as the Flight to Varennes, caused a rift in the Jacobin Club, where the most radical members began demanding the deposition of Louis XVI, who they felt could no longer be trusted. At this point in the Revolution, moderates feared that punishing the king would undermine the constitutional monarchy they had worked so hard to build. Despite Robespierre's efforts to keep the club together, the moderates split off and formed the new Feuillant Club which championed a liberal, constitutional monarchy. This split only entrenched Robespierre's power in the Jacobins, as those who remained were the most radical revolutionaries.

On 17 July 1791, when demonstrators gathered to demand the deposition of the king, they were fired on by National Guards in the Champ de Mars Massacre. After the massacre, the dominant Feuillants ordered the arrests of leading Republican agitators, and although Robespierre was not yet a Republican, he still laid low for a time. He began lodging with a supporter, the cabinetmaker Maurice Duplay, with whom he would live for the rest of his life. He became close with the Duplays, particularly the eldest daughter, Éléonore, who shared his political convictions and was often seen walking with him on the Champs-Élysées. Contemporaries whispered that the pair were secretly engaged or, more scandalously, that Éléonore was Robespierre's mistress. Neither rumor can be confirmed beyond speculation; however, Éléonore refused to marry after Robespierre's death and only ever wore black, leading some to call her "the Widow Robespierre".

Opposition to War

The constitution was adopted in September 1791, and the Constituent Assembly was disbanded in favor of the next government, the Legislative Assembly. Robespierre had successfully motioned for a self-denying ordinance that prevented any member of the current Constituent Assembly to serve on the Legislative. So, after his term expired, he returned to Arras where he was welcomed as a hero. However, he was soon back in Paris to resume his leadership in the Jacobin Club, where he continued to exert political influence from the sidelines.

By December, the Legislative Assembly had become dominated by a new faction, the Girondins, who began pushing for war with Austria; led by Jacques-Pierre Brissot, the Girondins believed war to be the only means of protecting the Revolution from its enemies. Robespierre fiercely opposed this, believing war could only bring about the Revolution's implosion and would result in a military dictatorship. He pushed back on Brissot's claim that oppressed Europe would welcome French armies as liberators, stating "no one likes armed missionaries". His disagreement with Brissot quickly devolved into a deep personal hatred. The Jacobins who supported Robespierre in this would later be known as the Mountain and develop a rivalry with the Girondins. In this instance, however, the Girondins won out, and on 20 April 1792, France declared war on Austria, sparking the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802).

Robespierre was soon vindicated in his fears. The war began terribly for the French, as a Prussian-led army commenced a slow advance towards Paris. In August, the invaders issued the Brunswick Manifesto, threatening to destroy Paris should any harm come to the king and queen. This catapulted Paris into a hysterical panic, resulting in the Storming of the Tuileries Palace, which toppled the monarchy, and the subsequent September Massacres, in which over 1,100 'counter-revolutionaries' were brutally slaughtered in their prison cells. After a brief tenure serving on the Insurrectionary Commune, headed by fellow radical Georges Danton, Robespierre was elected to the new National Convention, which was assembled to write yet another constitution for a now kingless France. Robespierre's younger brother, Augustin, was also elected to the Convention and became an influential Jacobin in his own right. On 20 September, the French defeated the Prussians at the Battle of Valmy, and the next day, the French Republic was established.

The Mountain

Robespierre and his supporters believed there was no place for a king in a republic, even a deposed king, and advocated for Louis XVI to be immediately put to death without trial. For Robespierre, Louis' guilt had already been decided when the people overthrew him, and, because Louis was a rallying point for counter-revolution, anything less than execution would jeopardize the Republic; "Louis must die," Robespierre proclaimed, "because the nation must live" (Scurr, 245). In this, Robespierre was fervently supported by the 25-year-old deputy Louis Antoine Saint-Just, who would soon become his closest ally. Ultimately, a trial was held and Louis XVI was sentenced to death and guillotined on 21 January 1793. The trial and execution of Louis XVI created another rift between the Mountain and the Girondins, who had worked to spare the former king's life.

The spring and summer of 1793 saw tensions between the two groups rise. The Mountain, coalescing around the leadership of radicals like Robespierre, Danton, and Jean-Paul Marat, drew its power from the Paris sans-culottes and appealed to them against efforts by the Girondins to decentralize power from Paris. Pro-Mountain pamphleteers like Robespierre's childhood friend Desmoulins succeeded in painting the Girondins as foreign agents who meant to fracture the Republic through federalism; this propaganda helped cause the insurrection of 2 June 1793, which resulted in the fall of the Girondins and the arrests of their leaders.

With the purge of the Girondins, the Mountain now controlled the Republic. Quickly, France began to unravel as provinces erupted into the federalist revolts and other rebellions against Jacobin rule. A Girondist sympathizer, Charlotte Corday, committed the assassination of Marat in July, an event that convinced Robespierre his own murder was imminent: "The honor of the dagger," he once said, "is also reserved for me…my downfall draws near with great strides" (Furet, 298). He predicted his demise with pride, believing that a premature death was the price a virtuous man must be willing to pay.

In April 1793, the Committee of Public Safety was created to deliver France from its enemies, both foreign and domestic. On 27 July, Robespierre was appointed to the Committee; through his fame and existing connections in the Jacobins he soon became its dominant member. In August, the Committee passed the levée en masse, a policy of mass conscription that helped turn the tide of the wars; it also implemented the Law of the General Maximum to alleviate starvation by putting price caps on bread. The Jacobins also abolished colonial slavery and drafted a constitution which was more democratic than any of its predecessors.

Reign of Terror

Despite these successes, the Republic was still in danger. Robespierre spoke frequently of evildoers disguised as patriots who meant to destroy the Republic from within. In September 1793, the Law of Suspects was enacted which allowed for the arrests of anyone who appeared counter-revolutionary in their words, actions, or writings; on 10 October, a motion passed by Saint-Just proclaimed the government to be "revolutionary until the peace", thereby shelving the new constitution indefinitely, and giving the Committee of Public Safety near dictatorial powers.

In the coming months, 300,000 to half a million people were arrested as suspects. 16,594 of them met their end beneath the guillotine's blade, while additional thousands died in prison or in summary massacres. Some victims were defeated revolutionary leaders, old regime aristocrats, or military officers accused of cowardice; most were ordinary people, caught up in the rising tide of patriotic bloodshed. Robespierre defended it by insisting that traitors were successfully being rooted out of society; total virtue, he argued, could only be achieved through Terror. He was content to build his perfect republic atop a mountain of corpses.

Robespierre maintained that the Terror was not born from his own ambitions, but rather as a way of protecting the Revolution from its enemies. Yet because Robespierre equated himself with the Revolution, the line between counter-revolutionaries and Robespierre's own political opponents became blurred; to oppose Robespierre and to oppose the Revolution became the same thing. The 'ultra-revolutionary' followers of journalist Jacques-René Hébert, for instance, were executed because they sought to intensify the Terror and impose atheistic policies. The moderate Indulgents, which included Robespierre's former friends Danton and Desmoulins, were executed only weeks later for the opposite reason, as they wished to see the Terror scaled back or even ended. Both groups had threatened Robespierre's power, and both had been eliminated.

In May 1794, an assassination attempt was made on Robespierre's life. He responded by intensifying the Terror; the Law of 22 Prairial eliminated the need for evidence to be presented before the Revolutionary Tribunal and ensured only one of two verdicts could be rendered: acquittal or death. In the period between the enactment of the law on 10 June and Robespierre's fall on 28 July 1794, 1,400 people were guillotined in Paris alone. Meanwhile, Robespierre continued his quest for moral excellence by creating the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being, centered around himself as a virtual high priest. This was too much for his enemies, who began plotting against him.

Downfall

The men who brought down Robespierre were less concerned with stopping the bloodshed than they were with saving their own skins. Many had been agents of the Terror who either engaged in corruption or were too excessive in their cruelties; fearing Robespierre's wrath, they decided to strike first. Between 18 June and 26 July 1794, Robespierre seldom appeared publicly for unknown reasons, leading to speculation that his health was failing or that the stresses of the Terror had caused a mental break. In any case, his absence allowed the conspirators time to gather and denounce him as a murderer. Robespierre returned on 26 July to defend himself, announcing he had a list of traitors within the National Convention and within the Committee of Public Safety itself. He refused to name any names, causing an uproar amongst the gathered deputies.

The next day, Robespierre and Saint-Just were again denounced as tyrants. The Convention declared them outlaws, forcing Robespierre and his followers to hide out in the Hôtel de Ville. At 2 am on 28 July, soldiers loyal to the Convention stormed the Hôtel, taking the Robespierrists into custody; in the confusion, Robespierre's jaw was shattered by a bullet, either self-inflicted or fired by a trigger-happy soldier. Condemned to death, Robespierre was executed alongside 21 of his closest allies, including Saint-Just and his brother Augustin; when it was Robespierre's turn to die, the executioner ripped off his bandages, causing him to utter an agonized scream that was only silenced when the blade fell. The fall of Maximilien Robespierre resulted in the end of the Terror and of Jacobin dominance, as the ensuing Thermidorian Reaction pursued more conservative policies.