Religious practice in medieval Europe (c. 476-1500) was dominated and informed by the Catholic Church. The majority of the population was Christian, and "Christian" at this time meant "Catholic" as there was initially no other form of that religion. The perceived corruption of the medieval Church, however, inspired the movement known today as the Protestant Reformation.

Early so-called proto-reformers such as John Wycliffe (l. 1330-1384) and Jan Hus (l. c. 1369-1415) inspired Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) and they were inspired by earlier religious sects, condemned as heresies by the Church, such as the Bogomils and Cathars, among many others, who called attention to the corruption and abuses of the Church. Even so, at the same time these criticisms may have had merit, the Church kept sight of its vision of working for the benefit of the people through its various institutions caring for the sick, poor, widows and orphans, and providing educational and vocational opportunities for women.

While it is true the Church focused on regulating and defining an individual's life in the Middle Ages, even if one rejected its teachings, and the clergy were often not the most qualified, it was still recognized as the manifestation of God's will and presence on earth. The dictates of the Church were not to be questioned, even when it seemed apparent that many of the clergy were working more in their own interests than those of God because, even if God's instruments were flawed, it was understood that the Creator of the universe was still in control.

A dramatic blow to the authority of the Church came in the form of the Black Death pandemic of 1347-1352 during which people began to doubt the power of God's instruments who could do nothing to stop people from dying or the plague from spreading. Although the Black Death was hardly the only cause of the fracture of the Church's power, it challenged the claim that it understood and represented the will of God. This challenge went unanswered and encouraged clerics such as Wycliffe and Hus to question further and, finally, Luther's objections which launched the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648) and broke the power of the medieval Church.

Church Structure & Beliefs

The Church claimed authority from God through Jesus Christ who, according to the Bible, designated his apostle Peter as "the rock upon which my church will be built" to whom he gave the keys of the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 16:18-19). Peter was therefore regarded as the first pope, the head of the church, and all others as his successors endowed with the same divine authority.

By the time of the Middle Ages, the Church had an established hierarchy:

- Pope – the head of the Church

- Cardinals – advisors to the Pope; administrators of the Church

- Bishops/Archbishops – ecclesiastical superiors over a cathedral or region

- Priests – ecclesiastical authorities over a parish, village, or town church

- Monastic Orders – religious adherents in monasteries supervised by an abbot/abbess

The Church maintained the belief that Jesus Christ was the only begotten son of the one true God as revealed in the Hebrew scriptures and that those works (which would become the Christian Old Testament) prophesied Christ's coming. The date of the earth and history of humanity were all revealed through the scriptures which made up the Christian Bible – considered the word of God and the oldest book in the world – which was understood as a handbook on how to live according to divine will and gain everlasting life in heaven upon one's death.

Interpretation of the Bible, however, was too great a responsibility for the average person, according to the Church's teachings, and so the clergy was a spiritual necessity. In order to talk to God or understand the Bible correctly, one relied on one's priest as that priest was ordained by his superior who was, in turn, ordained by another, all under the authority of the pope, God's representative on earth.

The Church hierarchy reflected the social hierarchy. One was born into a certain class, followed the profession of one's parents, and died as they had. Social mobility was a rarity since the Church taught that it was God's will one had been born into a certain set of circumstances and attempting to improve one's life was tantamount to claiming God had made a mistake. People, therefore, accepted their lot and made the best of it.

Church in Daily Life

The lives of the people of the Middle Ages revolved around the Church. People, especially women, were known to attend church three to five times daily for prayer and at least once a week for services, confession, and acts of contrition for repentance. The Church paid no taxes and was supported by the people of a town or city. Citizens were responsible for supporting the parish priest and Church overall through a tithe of ten percent of their income. Tithes paid for baptism ceremonies, confirmations, and funerals as well as saint's day festivals and holy day festivals such as Easter celebrations. Further, they supported social institutions including poor houses, orphanages, schools, and religious orders that could not support themselves.

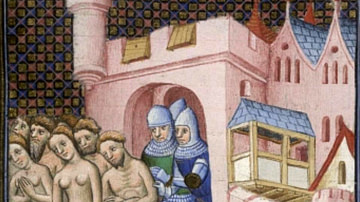

The center of a congregation's life in a small-town church or city cathedral was not the altar but the baptismal font. This was a free-standing stone receptacle/basin used for infant or adult baptism – often quite large and deep – which also served to determine a person's guilt or innocence when one was charged with a crime.

To clear one's name, a person would submit to an ordeal in which one was bound and dropped into the font. If the accused floated, it was a clear indication of guilt; if the accused sank, it meant innocence but the accused would often drown.

Under the reign of the English king Athelstan (r. 924-939), the procedure for the ordeal was codified as law:

If anyone pledges to undergo the ordeal, he is then to come three days before to the mass-priest whose duty it is to consecrate it [the ordeal], and live off bread and water and salt and vegetables until he shall go to it, and be present at mass on each of those three days, and make his offering and go to communion on the day on which he shall go to the ordeal, and swear then the oath that he is guiltless of that charge according to the common law, before he goes to the ordeal. (Brooke, 107)

There was also the ordeal of iron in which the accused was forced to hold or carry a hot poker. If the person could hold the red-hot iron without burning and blistering their hands, they were innocent; there are no records of anyone being found innocent. The ordeal of water was also carried out by streams, rivers, and lakes. Women accused of witchcraft, for example, were often tied in a sack with their cat (thought to be their demonic familiar) and thrown into a body of water. If they managed to escape and come to the surface, they were found guilty and then executed, but they most often drowned.

Ordeals, like executions, were a form of public entertainment and, as with festivals, marriages, and other events in community life, were paid for by the people's tithe to the Church. The lower class, as usual, bore the brunt of the Church's expenses but the nobility was also required to donate large sums to the Church to ensure a place for themselves in heaven or to lessen their time in purgatory.

The Church's teachings on purgatory – an afterlife realm between heaven and hell where souls remained until they had paid for their sins – generated enormous wealth for various clergy who sold writs known as indulgences, promising a shorter stay in purgatory for a price. Relics were another source of income, and it was common for unscrupulous clerics to sell fake splinters of Christ's cross, a saint's finger or toe, a vial of water from the Holy Land, or any number of objects, which would allegedly bring luck or ward off misfortune.

The teachings of the Church were a certainty to the people of the Middle Ages. There was no room for doubt, and questions were not tolerated. One was either in the Church or out of it, and if out, one's interactions with the rest of the community were limited. Jews, for example, lived in their own neighborhoods surrounded by Christians and were regularly treated quite poorly. The French king Charles Martel (r. 718-741), defeated the Muslim invasion of Europe at the Battle of Tours (also known as the Battle of Poitiers, 732), and Muslims in Europe were rare at this time outside of Spain and the traveling merchants conducting trade.

A citizen of Europe, therefore – who did not belong to either of these faiths – had to adhere to the orthodox vision of the Church in order to interact with family, community, and make a living. If one found one could not do so (or at least appear to do so), the only option was a so-called heretical sect.

Corruption & Heresy

The heretical sects of the Middle Ages were uniformly responses to perceived corruption of the Church. The immense wealth of the Church, accrued through tithes and lavish gifts, only inspired a desire for even greater wealth which translated as power. An archbishop could, and frequently did, threaten a noble, a town, or even a monastery with excommunication – by which one was exiled from the Church and so from the grace of God and commerce with fellow citizens – for any reason. Even well-known and devout religious figures – such as Hildegard of Bingen (l. 1098-1179) – were subject to 'discipline' along these lines for disagreeing with an ecclesiastical superior.

The priests were often corrupt and, in many cases, only held their position due to family influence and favor. Scholar G. G. Coulton cites a letter of 1281 in which the writer warns how "the ignorance of the priests precipitates the people into the ditch of error" (259) and later cites the correspondence of one Bishop Guillaume le Maire from Angers, who writes:

The Priesthood includes innumerable contemptible persons of abject life, utterly unworthy in learning and morals, from whose execrable lives and pernicious ignorance infinite scandals arise, the Church sacraments are despised by the laity, and in very many districts the lay folk hold the priests as [vile]. (259)

The medieval mystic Margery Kempe (l. C. 1342-1438) challenged the wealthy clerics to reform their corruption while, almost 200 years before, Hildegard of Bingen had done the same as had men like John Wycliffe and Jan Hus.

Some of those who objected to the policies of the Church joined alternate religious sects and attempted to live peacefully in their own communities. The best-known of these were the Cathars of Southern France who, while they interacted with the Catholic communities they lived near or in, had their own services, rituals, and belief system.

These kinds of communities were routinely condemned by the Church and destroyed, their members massacred, and whatever lands they had confiscated as Church property. Even an orthodox community which adhered to Catholic teachings – such as the Beguines – was condemned because it was begun spontaneously as a response to the needs of the people and was not initiated by the Church. The Beguines were laywomen who lived as nuns and served their community, holding all possessions in common and living a life of poverty and service to others, but they were not approved by the Church and were therefore condemned; they were disbanded along with their male counterparts, the Beghards, in the 14th century.

These groups, and others like them, attempted to assert spiritual autonomy based on the scriptural authority of the Bible, without any of the Church's ritual. The Cathars believed that Christ never died on the cross and was therefore never resurrected but that, instead, the son of God had been spiritually offered for the sins of humanity on a higher plane. The gospel stories, they claimed, should be understood as allegories using symbolic language rather than static histories of a past event. They further advocated for the feminine principle in the divine, revering a feminine principle of the godhead (known as Sophia), to whom they devoted their lives.

Living simply and serving the surrounding community, the Cathars amassed no wealth, their priests owned nothing, and were highly respected as holy men even by Catholics, and Cathar communities offered worthwhile goods and services. The Beguines, while never claiming any beliefs outside of orthodoxy, were equally devout and selfless in their efforts to help the poor and, especially, poor single mothers and their children. Both of these movements, however, offered people an alternative to the Church which the Church's teachings condemned.

Reformation

John Wycliffe and his followers (known as Lollards) had been calling for reformation since the 14th century, and it might be difficult for a modern-day reader to fully understand why no serious attempts were made at reform, but this is simply because the modern era offers so many different legitimate avenues for religious expression. In medieval Europe, it was inconceivable that there could be any valid Christian belief system outside of the Catholic Church.

Heaven, hell, and purgatory were all very real places to the people of the Middle Ages, and one could not risk offending God by criticizing his Church and damning one's self to an eternity of torment in a lake of fire surrounded by demons. The wonder is not so much why more people did not call for reform as that anyone was brave enough to try.

The Protestant Reformation did not arise as an attempt to overthrow the power of the Church but began simply as yet another effort at reforming ecclesiastical abuse and corruption. Martin Luther was a highly-educated German priest and monk who moved from concern to outrage over what he saw as abuses of the Church. Martin Luther's 95 Theses (1517) famously criticized the sale of indulgences as a money-making scheme having no biblical authority and no spiritual worth and opposed the Church's teachings on a number of other matters.

Luther was condemned by Pope Leo X in 1520 who demanded he renounce his criticism or face excommunication. When Luther refused to recant, Pope Leo moved ahead with the excommunication in 1521, and Luther became an outlaw. Like Wycliffe, Hus, and others before him, Luther was only calling for a reform of Church policy and practice. Like Wycliffe, he translated the Bible from Latin into the vernacular (Wycliffe from Latin to Middle English and Luther from Latin to German), opposed the concept of sacerdotalism whereby a priest is necessary as an intermediary between a believer and God, and maintained that the Bible and prayer were all one needed to commune directly with God. In making these claims, of course, he not only undermined the authority of the pope but rendered that position – as well as those of the cardinals, bishops, archbishops, priests, and others – ineffectual and obsolete.

According to Luther, salvation was granted by the grace of God, not by the good deeds of human beings, and so all of the works the Church required of people were of no eternal use and only served to fill the Church's treasury and build their grand cathedrals. Owing to the political climate in Germany, and Luther's own charisma and clever use of the printing press, his effort at reform, unlike earlier initiatives, was successful. Other reformers, such as Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) and John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) continued the movement in their own regions and many others followed suit afterwards.

Conclusion

The monopoly the Church held on religious belief and practice was broken, and a new era of greater spiritual freedom was begun, but it was not without cost. In their zeal to throw off the authority of the medieval Church, the newly liberated protestors destroyed monasteries, libraries, and cathedrals, the ruins of which still dot the European landscape in the present day.

The Church, as its own representatives understood at the Council of Trent, had failed to be its best and its clergy was frequently characterized far more by a love of worldly goods and pleasures than spiritual pursuits but at the same time, as noted above, the Church had initiated hospitals, colleges and universities, social systems for the care of the poor and the sick, and maintained religious orders which allowed women an outlet for their spirituality, imagination, and ambitions. These institutions became especially important during the Black Death pandemic of 1347-1352 when the Church did its best to care for the sick and dying when no one else would.

The Protestant Reformation, unfortunately, destroyed much of the good the medieval Church had done in reacting to what reformers understood as corruption and its perceived failure to meet the challenge of providing a reason, and solution, for the plague outbreak. Eventually, the different movements would organize into the Christian Protestant sects recognizable today – Lutherans, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, and so on – and set up their own institutes of higher learning, hospitals, and social programs. When the Reformation began, there was only the Church, the monolithic powerhouse of the Middle Ages, which afterwards became only one option of Christian religious expression among many.