Medieval literature is defined broadly as any work written in Latin or the vernacular between c. 476-1500, including philosophy, religious treatises, legal texts, as well as works of the imagination. More narrowly, however, the term applies to literary works of poetry, drama, romance, epic prose, and histories written in the vernacular, though some histories were in Latin.

While it may seem odd to find histories included with forms of fiction, it should be remembered that many 'histories' of the Middle Ages contain elements of myth, fable, and legend and, in some cases, were largely the creations of imaginative writers.

Language & Audience

Literary works were originally composed in Latin, but poets began writing in vernacular (the common language of the people) as early at the 7th century. Vernacular literature was further popularized in Britain in the Kingdom of Wessex by Alfred the Great (r. 871-899) in an attempt to encourage widespread literacy, and other regions then followed suit.

The Norman Conquest of 1066 established French as the language of literature and transformed the English language from Old English (in use c. 500-1100) to Middle English (c. 1100-1500). The stories written during both these eras were originally medieval folklore, tales transmitted orally, and since most of the population was illiterate, books continued to be read out loud to an audience. The aural aspect of literature, therefore, affected the way it was composed. Writers wrote for a performance of their work, not a private reading in solitude.

Literacy rates rose during the 15th century, and with the development of the printing press, more books became available. The act of reading by one's self for personal pleasure became more common and this changed the way writers wrote. Thomas Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur (written 1469, published 1485) is the earliest novel in the west – a work written for an individual audience with layers of personal meaning and symbolism – and set the foundation for the development of the novel as recognized in the present day.

Early Development

Medieval vernacular literature evolved naturally from the folktale which was a story recited, probably with the storyteller acting out different parts, before an audience. Medieval English literature begins with Beowulf (7th-10th century) which was no doubt a story known much earlier and transmitted orally until written down. This same pattern of development holds for the literature of other countries as well. The storyteller would gather an audience and perform his or her tale, usually with variations based on the audience, and members of that audience would then retell the story to others.

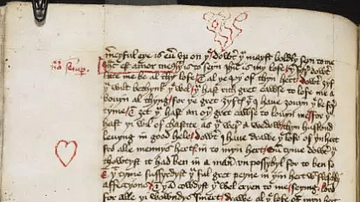

Early written medieval literature is mostly legend or folktale set down on a page rather than recited but the storyteller still needed to gather and hold an audience and so wrote in the vernacular to be understood and in poetic meter to be remembered. Poetry, with its regular cadence, sticks in the mind far better than prose. Poetry would remain the preferred medium for artistic expression throughout most of the Middle Ages.

Latin prose, except in some outstanding cases, was reserved for religious and scholarly audiences. For entertainment and escape from one's daily life, people listened to a storyteller read from a good book of verse. Lyric poetry, ballads, and hymns were poetry, of course, but the great chivalric romances of courtly love and the high medieval dream vision genres were also written in verse as were epics, and the French and Breton lais (short-story poems).

Initially, medieval writers were anonymous scribes setting down stories they had heard. Originality in writing in the Middle Ages (as in the ancient world) was not high on the list of cultural values and early writers did not bother to sign their works. The actual names of many of the most famous writers of the Middle Ages are still unknown. Marie de France is not the actual name of the woman who wrote the famous lais – it is a pen name – and Chretien de Troyes' name translates from the French as "a Christian of Troyes" which could refer to almost anyone. It was not until the 13th and 14th centuries that authors began writing under their own names. Whether known or anonymous, however, these writers created some of the greatest works of literature in history.

Other Forms of Literature

Other forms of literature besides poetry included:

- drama

- histories

- fables.

Drama in the Middle Ages was essentially a teaching tool of the Church. Morality plays, mystery plays, and liturgical plays all instructed an illiterate audience in acceptable thought and behavior. Passion plays, reenacting the suffering, crucifixion, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, were popular Easter entertainments but morality plays were presented year-round. The best-known of these is Everyman (c. 1495), which tells the story of a man facing death who cannot find anyone to accompany him to heaven except his good deeds. This allegory grew out of an earlier Latin type of literature known as the ars moriendi (art of dying) which instructed people on how to live a good life and be assured of heaven.

Histories in the Early Middle Ages (476-1000) frequently rely on fable and myth to round out and develop their stories. The works of historians such as Gildas (500-570), Bede (673-735), and Nennius (9th century) in Britain all contain mythic elements and repeat fables as fact. The most famous example of this is Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain (1136) written in Latin. Geoffrey claimed to be translating an ancient historical work he recently discovered when in fact he was making most of his 'history' up out of his own imagination and pieces in older actual histories which lent themselves to the tale he wanted to tell. His grand vision of the early kings of Britain focuses largely on the story of the heroic Arthur and it is for this reason that Geoffrey of Monmouth is recognized as the Father of the Arthurian Legend.

Fables almost always featured anthropomorphized animals as characters in relaying some moral lesson, satirizing some aspect of humanity, or encouraging a standard of behavior. The most popular and influential cycle of fables were those featuring Reynard the Fox (12th century onwards) whose adventures frequently brought him into conflict with Isengrim the Wolf. Reynard is a trickster who relies on his wits to get him out of trouble or to gain some advantage.

In one tale, How Reynard Fought Isengrim the Wolf, Isengrim challenges Reynard to a fight to the death to win the favor of the king. Reynard knows he cannot win but also cannot refuse so he asks his aunt for help. She shaves off all his fur and coats him in slick fat and he winds up winning because the wolf cannot get hold of him. The fable ends with Reynard being commended by the king. As with most fables, the underdog comes out a winner against overwhelming odds, and this theme made the tales of Reynard the Fox, and other similar characters, immensely popular.

Poetic Forms & Famous Works

Even so, the most popular and influential works were the stories told in verse. The earliest poem in English, whose author is known, is Caedmon's Hymn (7th century) which is a simple hymn praising God composed by an illiterate shepherd who heard it sung to him in a vision. His song was written down in Old English by an unnamed scribe at Whitby Abbey, Northumbria and first recorded in the writings of Bede. The simple beauty of this early verse became the standard of Old English poetry as evident in works like The Dream of the Rood (a 7th-century dream vision) and later The Battle of Maldon (late 10th century).

Between these two works, the epic masterpiece Beowulf was written, which relies on the same cadence of the alliterative long line rhythm to move the story forward and impress the tale upon an audience. This verse form resonates in the present day as well as it must have in the past since recitations and performances of Beowulf remain popular. The story is the epic tale of the lone hero facing down and defeating the dark monster that threatens the people of the land; a theme perennially popular from ancient times to the present day.

A later French work, The Song of Roland (11th century), is another epic which explores the same theme. In the French work, however, the 'monster' is given the human form of the Saracens threatening Christian lives and culture. Roland, the great knight of Charlemagne, is finally called upon to hold the pass of Roncevaux against the advancing enemy and gives his life to protect his king, country, and comrades from the invaders. The poem was so popular it is said to have been sung by the Norman troops at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 to boost morale.

Romances, which became quite popular with the European aristocracy, began to flourish in the 12th century in southern France. Chretien de Troyes (l. c. 1130-c.1190), poet of the court of Marie de Champagne (l. 1145-1198) is the best known of the romantic poets and certainly among the most influential. Chretien's poems about the damsel in distress and the brave knight who must rescue her became quite popular and contributed to the development of the legend of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, which would finally be fully realized by Malory.

The romance genre, whether given in poetry or prose, relies on the audience's acceptance of the concept that true love can never last or is unattainable. At the end of the story, one or both of the lovers die or must part. The concept of a happily-ever-after ending, popular in medieval folklore, rarely concludes a written medieval romance. According to some scholars, this is because the romantic literature of courtly love was a cleverly coded 'scripture' of the Cathars, a heretic religious sect persecuted by the medieval Church. The Cathars ("pure ones" from the Greek Cathari) claimed they were the true faith and venerated a feminine divine principle named Sophia (wisdom) who bore a number of similarities to the Virgin Mary.

According to the scholarly theory regarding the Cathars and the medieval romance, the damsel in distress is Sophia and the brave knight is the Cathar adherent who must protect her from danger (the Church). Two of the most powerful women of the Middle Ages, Marie de Champagne and her mother Eleanor of Aquitaine (l. c. 1122-1204) were both associated with the Cathar heresy and both patronesses of writers of the romances such as Chretien de Troyes, Andreas Cappelanus, and most likely Marie de France, so there is some historical support for the theory.

Whether the romances were allegorical works, their elevation of women in the fictive worlds of the chivalric hero influenced the way women were perceived – at least in the upper classes – in everyday life. The genre was developed further in the 12th and 13th centuries by poets such as Robert de Boron, Beroul, and Thomas of Britain, and the great German artists Wolfram von Eschenbach (l. 1170-1220) and Gottried von Strassburg (l. c. 1210), who all contributed significant aspects to the Arthurian legend.

By the time of the 14th century, however, the medieval view of woman-as-property had been largely replaced by the novel concept of woman-as-individual famously exemplified by Geoffrey Chaucer in the character of the Wife of Bath in The Canterbury Tales. Women appear in Chretien's works as strong individuals in the 12th century – most famously the character of Guinevere in the poem Lancelot or the Knight of the Cart – but the Wife of Bath is much more rounded and complete individual who owes her composition as much to the French fabliaux (a short story told in verse) as to the romances or figures from folklore.

The elevation of womanhood reached its apex in the poetry of Petrarch (l. 1304-1374) whose sonnets to the persona of Laura continue to resonate in the modern day. Petrarch's work was so popular in his time that it influenced social perceptions not only of women but of humanity in general which is why he is often cited as the first humanist author.

While the romances entertained and edified, another genre sought to elevate and console: the high medieval dream vision. Dream visions are poems featuring a first-person narrator who relates a dream which corresponds to some difficulty they are experiencing. The most famous of these is The Pearl by an unknown author, Piers Plowman by William Langland, and Chaucer's Book of the Duchess, all from the 14th century. The genre usually relies on a framing device by which a reader is presented with the narrator's problem, is then taken into the dream, and is then brought back again to the narrator's waking life.

In The Pearl, the narrator is grieving the loss of his daughter, has a dream of her new life in heaven where she is safe and happy, and wakes reconciled to the loss of his "precious pearl without a price". The father's grief is relieved by God allowing him to see where his daughter has gone and how she has not ceased to exist but has simply found a new and brighter home. Piers Plowman also reveals the goodness and love of God to the dreamer, a man named Will, who is taken on a journey in his dreams in which he meets the good plowman, Piers, who represents Christ and who teaches him how to better live his life.

Chaucer's Book of the Duchess (his first major long poem, c. 1370) departs from the religious theme to focus on grief and loss and how one lives with it. In this work, the narrator's true love has left him and he has been unable to sleep for years. While reading a book about two lovers who have been parted by death, he falls asleep and dreams he meets a black knight in the woods who tells him of his own true love, their happy life together, and finally of his grief: his wife has died. The poem explores a central question of the courtly love romances: was it better to lose a lover to death or infidelity? The narrator never answers the question. When he wakes from the dream, he only tells the reader he was so amazed by it that he will write it down as a poem; he leaves it up to the reader to answer the question.

The medieval dream vision reaches its greatest height in Dante Alighieri' s Divine Comedy (14th century) in which the poet is taken on a journey through hell, purgatory, and paradise in order to correct the path he was on and assure him of the truth of the Christian vision. The Divine Comedy is not an actual dream vision – the narrator never claims he has fallen asleep or that the events are a dream – but Dante draws on the trappings of the genre to tell his story. So closely does The Divine Comedy mirror the progression, tone, and effect of the high medieval dream vision that contemporaries – and even Dante's own son – interpreted the piece as a dream.

Conclusion

Although poetry continued as a popular medium in the Late Middle Ages, more writers began working in prose and among these were a number of notable women. Female Christian mystics such as Julian of Norwich (l. 1342-1416) and Catherine of Sienna (l. 1347-1380) both related their visions in prose and Margery Kempe (l. 1373-1438) dictated her revelations to a scribe who recorded them in prose. One of the most famous writers of the Middle Ages, Christine de Pizan (l. 1364-c.1430) wrote her highly influential works in prose as did the great Italian artist Giovanni Boccaccio (l. 1313-1375) best known for his masterpiece, the Decameron.

The Arthurian Legend, developed from the 12th century onwards, was rendered in prose in the Vulgate Cycle between 1215-1235 and the edited version known as the Post-Vulgate Cycle (c. 1240-1250) which provided the basis for Malory's work. Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur codified the Arthurian Legend which was then enhanced and reworked by later writers and continues to exert influence in the present day.

Although scholars continue to debate precisely which work should be considered the first novel in English, Malory's work is always a strong contender. William Caxton, Malory's publisher, was one of the first to benefit from the new printing press invented by Johannes Gutenberg c. 1440. Gutenberg's press ensured that medieval literature, largely anonymous and free to whomever wanted to publish it, would survive to influence later generations of readers.