The Meiji Restoration was a political event that took place in Japan in 1868. In it, the Tokugawa family, a warrior clan that had ruled Japan for more than 260 years, was overthrown by a group of political activists who proclaimed that their goal was to restore the imperial family to power.

After they successfully overthrew the Tokugawa shogunate, Emperor Mutsuhito (1852-1912) adopted the reign title Meiji, which means "enlightened rule." The Meiji Restoration is almost universally regarded as the dividing line between 'traditional' and 'modern' Japan. While it did bring to power a new government that introduced radical policies that fundamentally altered Japanese society, because it was not an especially violent event in itself, there was also a great deal of continuity between pre- and post-Restoration Japan.

The causes of the Meiji Restoration can be summarised as follows:

- the bakuhan system

- foreign threat

- rise of imperial loyalism

The Bakuhan System

The first of the long-term causes can be found in the political system the Tokugawa imposed on Japan after the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. At that time, the Tokugawa controlled about 30% of the land in Japan, and about 270 hereditary daimyo families controlled the rest. The warrior government the Tokugawa established was called a bakufu, and the lands the daimyo controlled were called han. Modern historians call this arrangement the bakuhan system. Although the Tokugawa put in place various policies to control the daimyo, within their own han, they could more or less govern as they pleased. Most han were fairly small, but some, like Satsuma and Choshu, were very large. They were like countries within a country.

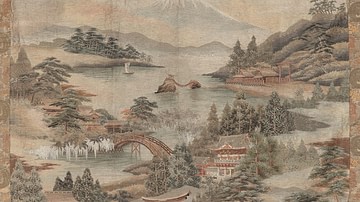

In the 17th century, the Tokugawa took vigorous action to keep the daimyo in line, but from the beginning of the 18th century, the system stayed in place mainly because of institutional inertia. The Tokugawa political system is often described as being feudal, but feudalism in medieval Japan was different from feudalism in Europe in the Middle Ages. At this time Japan experienced an exceptional period of peace in which the economy expanded, the population grew, cities developed, literacy and scholarship spread, and a new urban culture appeared. While the Tokugawa did impose a military dictatorship on Japan, it is better to think of the bakuhan system itself as a kind of federation in which the balance of power favoured the Tokugawa. At the beginning of the 19th century, however, that balance was upset by the threat from foreign countries.

The Foreign Threat

In the 1630s, one of the measures the Tokugawa had put in place to control the daimyo was to restrict contact with foreign countries through a policy of national isolation. The Tokugawa feared rebellious daimyo might get support from abroad, so they limited contact with Korea and China, and all Europeans except for the Dutch were excluded. Even the Dutch were confined to a trading post in Nagasaki. The Tokugawa had been able to adopt this policy partly because Japan was far from Europe and also because, in the 17th century, the level of technology in Japan and foreign countries was more or less the same. At the end of the 18th century CE, however, Europe began to experience the Industrial Revolution. At the beginning of the 19th century, European ships armed with industrial-age weapons began to approach Japan demanding that the country open to foreign trade. The Tokugawa rebuffed these demands. By 1839, however, Britain had already colonised India, and China's defeat in the Opium War (1839-42) was a signal to the Japanese government that their country was under real threat. In response, both the bakufu and some of the larger han made efforts to acquire European weapons.

In 1853, the American commander Mathew Perry (1794-1858) sailed a fleet of 'black ships' to Japan and demanded that the country open up ports for trade. The bakufu felt compelled to make some concessions, and in 1854, it agreed to the Japan-US Treaty of Peace and Amity, which opened the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to American ships. Similar agreements soon followed with Britain, Russia, and the Netherlands. Being compelled to sign these treaties exposed the weakness of the Tokugawa government, and opponents accused it of failing to defend the country. This was the second long-term cause of the restoration.

The Rise of Imperial Loyalism

The third long-term cause was the rise of imperial loyalism. The Emperor of Japan has reigned throughout Japanese history, but there have been few times when emperors actually exercised political power. In ancient times, power was mostly in the hands of the court aristocracy, and later in those of powerful warrior families like the Minamoto and Ashikaga. The same was true in the Edo period (1603-1868). Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616) had the emperor appoint him as shogun in 1603, and this gave him the right to establish the bakufu. This was just a political fiction, however, as the imperial family had no real power, and it was completely dependent on the bakufu for its survival. It was in the interests of the Tokugawa, however, to build up the prestige of the imperial family because this, in turn, gave them greater legitimacy.

In the 18th century, the imperial family began to acquire influence from a different source. From the middle of the 17th century, Chinese Neo-Confucian ideas began to spread to Japan. Not only were concepts such as loyalty and filial piety important in Confucianism but Confucian scholarship was also based on the critical study of ancient texts. The texts involved were, of course, Chinese ones, but some scholars began to apply the same analytical techniques to the study of ancient Japanese works such as the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki. These books contained accounts of the founding of the ancient Japanese state by emperors, who were described as being descended from the gods. The idea that Japan was a 'divine land' countered the Confucian presumption that only China was 'civilised and that surrounding countries like Korea and Japan were 'barbarian'. Some began to promote the idea that Japan was superior to foreign countries because of the divine origin of the imperial family. They also argued that government by warrior families like the Tokugawa was illegitimate and that the imperial family should directly rule the country. There was quite a diverse range of thinkers in this group, but it included people associated with kokugaku ("national learning" or "nativism") and the Mito School as well as more independent writers like Rai San'yo (1780-1832) whose book An Unofficial History of Japan (1827) became very influential.

Together, these three long-term causes led to the development of a movement that opposed both continued Tokugawa rule and the opening of the country. The goals of this movement were encapsulated in the slogan, "revere the emperor, expel the barbarians," which was coined by Aizawa Seishisai (1782-1863) in his book New Theses (1825).

Regional & Class Background of the Revolutionaries

During the Edo period, daimyo were divided into different categories depending on their family's connection with the Tokugawa. Those who had been Tokugawa retainers before the Battle of Sekigahara were called fudai daimyo, while those who had not were called tozama daimyo. The tozama daimyo were less trusted, and their territories tended to be large but far from the political centre of Japan. In the first half of the 19th century, the anti-Tokugawa movement largely developed in areas controlled by tozama daimyo:

Choshu (modern-day Yamaguchi Prefecture)

- Yoshida Shoin (1830-1859)

- Yamagata Aritomo (1838-1922)

- Ito Hirobumi (1841-1909)

Satsuma (Kagoshima Prefecture)

- Matsukata Masayoshi (1835-1924)

- Mori Arinori (1847-1889)

- Saigo Takamori (1828-1877)

- Okubo Toshimichi (1830-1878)

Hizen (Saga Prefecture)

- Okuma Shigenobu (1838-1922)

Tosa (Kochi Prefecture)

- Itagaki Taisuke (1837-1919)

- Sakamoto Ryoma (1836-1867)

Most of these activists came from low-ranking warrior families, although some members of the court nobility also played an important role including Iwakura Tomomi (1825-1888) and Saionji Kinmochi (1849-1940).

The Final Years of Tokugawa Rule

The last decades of the Edo period are referred to as the bakumatsu period. Baku comes from bakufu, and matsu means "end" in Japanese. In 1858, the bakufu signed the Japan-US Treaty of Amity and Commerce. This was an unequal treaty because it included a clause setting a low tariff on imported goods and another which meant foreigners were not subject to Japanese law. The import of cheap foreign goods had a negative impact on the Japanese economy and the opening of the ports increased hostility towards foreigners. Amongst those advocating the overthrow of the Tokugawa were a group of people referred to as shishi, or "righteous warriors." These were extremists who carried out violent attacks on both foreigners and Japanese whom they regarded as their enemies. Ii Naosuke (1815-1860), who was the most powerful bakufu official, tried to suppress this movement in a crackdown known as the Ansei Purge (1860). Many were arrested, and quite a few were executed. To strengthen the government, Ii advocated linking the imperial court and bakufu through the marriage of the emperor's sister to the shogun. In 1860, however, in a serious blow to the bakufu's prestige, he was assassinated near Edo Castle (Sakuradamon Incident).

In 1863, anti-foreign activists from Choshu seized control of the imperial court in Kyoto and Emperor Komei (1831-1867), who was also hostile to opening the country, issued an order to 'expel the barbarians.' The bakufu had no plans to implement this, but it inspired a number of attacks on foreigners. Shishi from Satsuma killed a foreign merchant, and in response the British bombarded Kagoshima. In Choshu, shore batteries fired on foreign vessels sailing through the Shimonoseki Strait. European warships retaliated by destroying the gun emplacements. The bakufu also launched a punitive expedition against Choshu, but a negotiated settlement was reached, and the attack was called off.

From these experiences, the activists in Satsuma and Choshu realized that 'expelling the barbarians' was impossible. To prevent Japan becoming a colony, it was necessary to overthrow the bakufu and create a new government. In 1866, the two han secretly formed an alliance, and Satsuma refused to participate in a second bukufu campaign against Choshu. Instead, it supported Choshu by supplying large quantities of weapons. In another blow to its prestige, the bakufu was defeated.

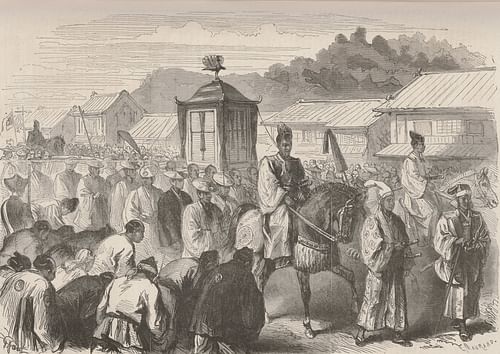

In November 1867, the last shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu (1837-1913) offered to peacefully relinquish power to Emperor Meiji, who had ascended to the throne after the death of Emperor Komei. However, elements in Satsuma and Choshu had already decided to overthrow the bakufu by force. In January 1868, they took control of the Imperial Palace in Kyoto and issued an edict restoring imperial rule. This set the stage for the Boshin War, a war between supporters of the court and the bakufu. The bakufu forces were defeated in the Battle of Toba-Fushimi south of Kyoto. A large imperial army then surrounded the city of Edo (modern-day Tokyo), but negotiations resulted in the peaceful surrender of Edo Castle. This avoided an attack on the city and guaranteed the personal safety of Yoshinobu. Resistance to the new government continued in northern Japan, but in June 1869, the last bakufu supporters surrendered at Hakodate in Hokkaido. This brought Tokugawa rule to an end after 268 years.

Although the Meiji Restoration had momentous consequences, it was not an especially violent event. It is thought that about 120,000 men were mobilised in the Boshin War of whom 8,200 died. In contrast, in the American Civil War, which took place at a similar time, three million people fought and about 620,000 died. The fact that the Meiji Restoration was not accompanied by a great deal of destruction was important because it meant the new Meiji government had a relatively stable foundation from which to launch its reforms.

The Significance of the Meiji Restoration

Probably the most common interpretation of the events is based on modernization theory. This theory developed in the 1950s and categorises societies as being either 'traditional' or 'modern'. Traditional societies are defined as having economies based on agriculture, being socially hierarchical and politically despotic, while modern ones are thought of as being industrial, egalitarian, and democratic. Modernization is regarded as the process by which a traditional society turns into a modern one. In the heyday of modernisation theory, Meiji-period Japan was often cited as a good example of this process, and the Meiji Restoration was viewed from this perspective.

Since the 1970s, however, modernization theory has largely been discredited. It was developed in the context of the Cold War as an alternate theory of development to the Marxist one offered by China and the Soviet Union. Amongst other things, it fails to take account of the great variation that exists amongst both so-called traditional societies and modern ones. Modernisation theory also has a racial aspect because it equates modern societies with those of Europe and North America. For this reason, Japan was seen as something of an anomaly, a non-western country that also became modern. To understand the Meiji Restoration, rather than approaching it from a theoretical perspective, it is best to think of it as an event that had both causes and consequences that were unique to Japan.