Memphis was one of the oldest and most important cities in ancient Egypt, located at the entrance to the Nile River Valley near the Giza plateau. It served as the capital of ancient Egypt and an important religious cult center.

The original name of the city was Hiku-Ptah (also Hut-Ka-Ptah) but it was later known as Inbu-Hedj which means 'White Walls' because it was built of mud brick and then painted white. By the time of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) it was known as Men-nefer ("the enduring and beautiful") which was translated by the Greeks into 'Memphis.' It was allegedly founded by the king Menes (c. 3150 BCE) who united the two lands of Egypt into a single country. The kings of the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150-2613 BCE) and Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) ruled from Memphis, and even when it was not the capital, it remained an important commercial and cultural center.

The city features prominently throughout Egypt's history from the earliest records of the Dynastic Era to the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE) but no doubt existed earlier in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (C. 6000-3150 BCE). The city's location at the entrance to the Nile River Valley would have made it a natural place for an early settlement. From the earliest times through the end of ancient Egyptian history in the Roman period, Memphis played a role in the lives of the people.

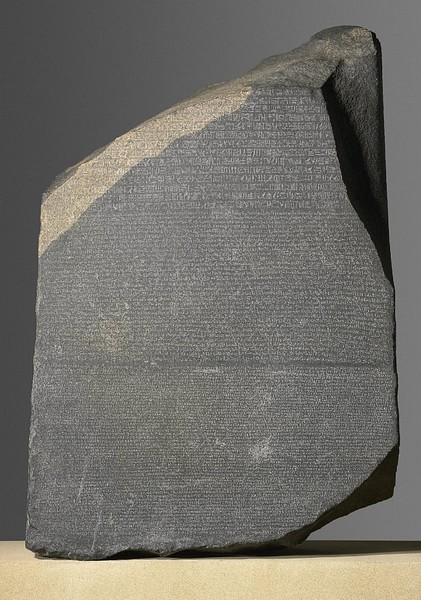

Kings ruled there, commerce took place in the markets, the great religious temples drew pilgrims and tourists, and some of the most famous kings of the country constructed their great monuments in or near the city. Alexander the Great had himself crowned pharaoh at Memphis, and the Rosetta Stone, the stele which unlocked the secret of Egyptian hieroglyphics, was originally issued from the city.

After the Romans annexed Egypt, Memphis began to decline. This was hastened by the rise of Christianity in the 4th century CE when people stopped visiting the old temples and shrines of the Egyptian gods. By the 7th century CE, following the Arab Invasion, Memphis was a ruin whose buildings were harvested for stone to lay the foundations for Cairo and for other projects.

Name & Significance

The 3rd-century BCE historian Manetho claims that the first king of Egypt, Menes, built the city after the unification of Egypt. At this time the city was known as Hiku-Ptah or Hut-Ka-Ptah meaning 'Mansion of the Soul of Ptah.' Ptah was probably an early fertility god during the Predynastic Period but was elevated to the position of 'Lord of Truth' and 'Creator of the World' by the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period. He was the protector god of the area around Memphis and became the patron deity of the city after it was built in his honor.

Other inscriptions credit the building of Memphis to Menes' successor Hor-Aha who is said to have visited the site, not the city, and so admired it that he changed the course of the Nile River to make a wide plain for construction. Hor-Aha has been equated with Menes owing to various inscriptions, but 'Menes' seems to have been a title meaning 'He Who Endures,' not a personal name, and may have been passed down from the first king. The original builder of the city was probably Narmer, the king who unified Egypt, who was known as Menes. The legend of Hor-Aha's visit and diversion of the river is most likely a version of an earlier tale told of Menes (Narmer) around whom many miraculous legends would grow.

The city's early name of Hut-Ka-Ptah gave Egypt its Greek name for the country. The Egyptians themselves called their country Kemet which means 'black land,' owing to the rich, dark soil. The name Hut-Ka-Ptah was translated by the Greeks as 'Aegyptos' which became 'Egypt.' It is a testament to the power and fame of early Memphis that the Greeks named the country after the city.

Early History

In the Early Dynastic Period, the city was referred to as Inbu-Hedj ('White Walls') because the mud brick walls were painted white and were said to gleam in the sun from miles away. There is no evidence the actual name of the city changed, however. This new epithet for the city probably came about at the beginning of the Third Dynasty of Egypt (c. 2670-c.2613 BCE) when Djoser came to power. Prior to this, the kings were buried at Abydos, but toward the end of the Second Dynasty of Egypt (c. 2890-c.2670 BCE) they were buried near Memphis, close to Giza.

Djoser is said to have elevated the status of the city by making it his capital, but it was already the seat of power in Egypt prior to his reign. It is more probable that he increased the city's prestige by choosing a nearby site, Saqqara, for his mortuary complex and pyramid tomb. The white walls of the city would have reflected the status of this king and called attention to his eternal home nearby.

Egyptologist Kathryn A. Bard writes, "The North Saqqara cemetery is on a prominent limestone ridge overlooking the valley and the presence of large, elaborately niched superstructures would have been very impressive symbols of status" (Shaw, 72). The city walls may have been painted white to further reflect this status. According to Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson, it was not the walls of the city but those of the central palace whose walls were painted white and gave the city its epithet. Wilkinson writes:

With its whitewashed exterior, this building known as White Wall must have been a dazzling sight, comparable in its symbolism to the White House of a modern superpower. Other royal buildings throughout the land were consciously modeled on White Wall. (31)

There is no doubt, however, that the city was already the capital of a unified Egypt prior to Djoser and held in high regard, so it is possible the walls of either the city or the palace were painted white before his reign. Bard notes that "tombs of high officials have been found at nearby North Saqqara and officials of all levels were buried at other sites in the Memphite region. Such funerary evidence suggests that Memphis was the administrative centre of the state" (Shaw, 64). Excavations have unearthed pottery and grave goods dating to the First Dynasty of Egypt, even though Manetho claims that Memphis did not become the capital until the Third Dynasty.

Capital of the Old Kingdom

During the Old Kingdom, the city continued as the capital. King Sneferu (c. 2613-2589 BCE) reigned in the city as he commissioned his great pyramids. Sneferu perfected the art of pyramid building and work in stone which had been initiated by Djoser's vizier and chief architect Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE) at Saqqara. Sneferu's successor, Khufu (c. 2589-2566 BCE), would build on his success to create the Great Pyramid at nearby Giza. His successors, Khafre (c. 2558-2532 BCE) and Menkaure (c. 2532-2503 BCE), built their own pyramids there after him. Memphis, as capital, was the seat and source of the intricate and far-reaching bureaucracy which enabled these kings to organize the kind of labor force and resources necessary to build their enormous complexes and pyramids.

By the time of the first king of the 5th Dynasty, Userkaf (c. 2498-2491 BCE), Giza was a flourishing necropolis administered by priests of the gods and featuring all the aspects of a small city including shops, factories, temples, streets, and private homes. Memphis continued to grow at this time as well and mirrored the developments at Giza. The Temple of Ptah became an important religious center, and monuments were raised throughout the city to honor this god.

At the same time, the cult of the sun god Ra was becoming more popular and the priests of Ra, who administered the complexes at Giza, were becoming more powerful. Userkaf, perhaps finding that there was no more room to build at Giza, chose nearby Abusir as the site for his mortuary complex and had a temple to Ra built in his honor, the first of many constructed in the 5th Dynasty when the cult of Ra was growing in popularity.

During the reign of the 6th Dynasty king Pepi I (c. 2332-2283 BCE) the city came to be known as Memphis. Historian Margaret Bunson explains:

Pepi I built his beautiful pyramid at Saqqara. That mortuary monument was called Men-nefer-Mare, the "Established and Beautiful Pyramid of Men-nefer-Mare". The name soon came to designate the surrounding area, including the city itself. It was called Men-nefer ["the enduring and beautiful"] and then Menfi. The Greeks, visiting the capital centuries later, translated the name to Memphis. (161)

The 6th Dynasty kings steadily lost power over the country as resources dwindled, the priests of Ra and local officials became more wealthy and powerful, and the authority of Memphis degenerated. During the reign of Pepi II (c. 2278-2184 BCE) the king's power declined steadily. A drought brought famine, which the government at Memphis could do nothing to alleviate, and the Old Kingdom's power structure collapsed.

The Rise of Thebes

Memphis continued to serve as the capital during the early part of the era known as the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181-2040 BCE). The records from this time period are often confused or missing, but it seems Memphis remained the capital throughout the 7th and 8th Dynasties with the kings claiming for themselves the authority and legitimacy of the Old Kingdom rulers. Their seat of power in the traditional capital, however, was the only aspect of rule they had in common with the earlier monarchs of Egypt. While they entertained themselves with the belief in their own authority, the local officials (nomarchs) of the districts began to rule their communities independently. There does still seem to be some acknowledgment of Memphis as the capital, but it was so in name only.

At some point either in the late 8th Dynasty or early 9th, the kings of Memphis moved the capital to the city of Herakleopolis, perhaps in an effort to revitalize their authority somehow. Their reasons for the move are unclear, but they had no more relevance to the country at Herakleopolis than they had had at Memphis.

The First Intermediate Period has traditionally been characterized as a "dark age" of chaos but was actually just a time when the regional governors held more power than the central government and Egypt was no longer unified under a single strong ruler. The nomarchs of the different districts experienced varying levels of success according to their individual talents and resources, but one city began to grow more powerful than the others, owing to the leadership of their nomarchs.

Thebes was just another provincial city in Upper Egypt when an official named Intef I (c. 2125 BCE) came to power. Intef I energized the Thebans and challenged the authority of the kings at Herakleopolis. His successors continued his policies, warring against the weak central government, until the reign of Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE), who overthrew the Herakleopolitan kings and unified Egypt under Theban rule.

Thebes now became the capital of Egypt, and the great monuments which had previously been lavished on Memphis now rose in this city. The early governor Wahankh Intef II (c. 2112-2063 BCE) is thought to be the first to raise a monument at Karnak and Mentuhotep II added to the grandeur of Thebes with his own mortuary complex. The city continued as capital only to the reign of Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE), who moved the capital north to Iti-tawi near Lisht.

Memphis and Thebes continued as important religious and cultural centers throughout the Middle Kingdom, however. Construction of the great Temple of Karnak continued at Thebes while at Memphis shrines and temples to the god Ptah increased. Amenemhat I raised a shrine to Ptah at Memphis and his successors also patronized the city adding their own monuments.

Even during the decline of the Middle Kingdom in the 13th Dynasty, the kings continued to honor Memphis with temples and monuments. Although the cult of the god Amun had grown more popular, Ptah was still honored at Memphis as the city's patron deity. Memphis continued as an important cultural and commercial center trading with districts throughout Egypt while attracting visitors to the temples and shrines.

Memphis in the New Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom was followed by another era of instability and disunity known as the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-1570 BCE) and characterized chiefly by the rise in power of a people known as the Hyksos who ruled Lower Egypt from Avaris. They took control of Egyptian cities from their northern stronghold and raided Memphis, carrying monuments back to Avaris. Although the later Egyptian writers claimed that the Hyksos destroyed Egyptian culture and oppressed the people, they actually admired the culture greatly and emulated it in their art, architecture, fashion, and religious observances.

Memphis shows evidence of severe damage during this period as the Hyksos removed structures to Avaris and destroyed others. The Hyksos were driven out of Egypt by Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE) of Thebes, who reunited Egypt and initiated the period known as the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE). Thebes again became the capital of Egypt, while Memphis continued its traditional role as a religious and commercial center.

The great kings of the New Kingdom all built at Memphis, raising temples and monuments. Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE) built a temple to his god Aten at Memphis during the Amarna Period when he closed the temples and banished the worship of all other gods. Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) moved the capital of the country to his new city of Per-Ramesses (at the site of Avaris) but honored Memphis with a number of enormous monuments. His successors continued the respect for Memphis, which was regarded as the Second City of Egypt after the capital.

Religious Importance & Later Significance

Memphis had always enjoyed a high level of prestige from its founding onwards and continued to be even after the decline of the New Kingdom into the Third Intermediate Period (1069-525 BCE). While a number of cities suffered from neglect during this period, Memphis' status remained unchanged. In 671 BCE, when the Assyrian king Esarhaddon (681-669 BCE) invaded Egypt, he made a point of sacking Memphis and carrying important members of the community back to his capital at Nineveh.

The religious importance of the city, however, ensured it would survive the Assyrian invasion and it was rebuilt. Memphis became a center of resistance against Assyrian occupation and was again destroyed by Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE), who invaded in 666 BCE. Ashurbanipal also sacked Thebes and other important cities and placed Assyrians in key positions throughout the country to maintain control.

Memphis again revived as a religious center, and under the Saite pharaohs of the 26th Dynasty (664-525 BCE), the city was rebuilt and fortified. The gods of Egypt, especially Ptah, continued to be worshiped there, and further shrines and monuments were built in their honor.

In 525 BCE, the Persian general Cambyses II invaded Egypt, defeating the army at Pelusium and marching on Memphis. He took the city and fortified it, making it the capital of the satrapy of Persian Egypt. When Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) took Egypt in 331 BCE, he had himself crowned pharaoh at Memphis, linking himself with the great monarchs of the past.

During the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE), which followed Alexander's death, the Greek pharaohs maintained the city at its traditional level of prestige. Ptolemy I (323-283 BCE) respected the city and had Alexander's body entombed there at the beginning of his reign. He further honored Memphis as he established his new cult of Serapis at nearby Saqqara. Ptolemy II (283-246 BCE) had Alexander's body removed to Alexandria and initiated a number of building projects there including the Serapeum, the great library, and the university. Alexandria became the jewel of Egypt and a center of learning and culture, but Memphis would begin to decline.

The city was still considered an important religious center, however, and the priests of the city were on par with secular authorities in power. The temples and shrines of the gods were rebuilt and renovated under the Ptolemies and new buildings were raised. Egyptologist Alan B. Lloyd writes:

The priests were based at numerous temples, which were frequently rebuilt or embellished in Ptolemaic times and still constitute some of the most spectacular and complete remains of pharaonic culture. (Shaw, 406)

These temples, at Memphis and elsewhere, were not just homes to the gods and centers of worship but factories of a kind, which produced clothing, artifacts, and artwork such as paintings. The temples of Memphis kept the city's reputation in good standing, but as the Ptolemaic Dynasty continued, it lost its status to Alexandria. The Memphis Decree (better known as the Rosetta Stone) was issued in 196 BCE by Ptolemy V, and after that, the city steadily lost its prestige.

Decline of Memphis

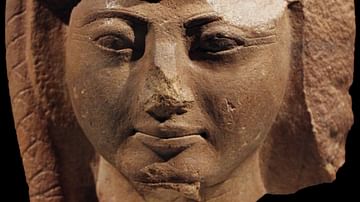

The Ptolemaic Dynasty ended with the death of the last queen, Cleopatra VII (69-30 BCE), and Egypt was annexed by Rome. Alexandria, with its great port and centers of learning, became the focal point of Roman government of Egypt, and Memphis was forgotten. With the rise of Christianity in the 4th century CE, Memphis declined further as fewer and fewer people visited the shrines and temples, and by the 5th century CE, when Christianity was the dominant religion of the Roman Empire, Memphis was in decay.

By the time of the 7th century CE Arab invasion, the city was in ruins. The temples, buildings, shrines, and walls were dismantled and used to build the city of Fustat, the first capital of Muslim Egypt, as well as the later city of Cairo. In the present day, nothing is left of the city of Memphis but stumps of pillars, foundations, the remains of walls, broken statues, and stray pieces of columns near the village of Mit Rahina.

The site was included by UNESCO on their World Heritage List in 1979 CE as a place of special cultural significance, and it continues to be a popular tourist attraction featuring a museum. The alabaster sphinx and the colossus of Ramesses II are especially impressive, and the site is admired by visitors in the present as much as the city of Memphis was by those of the ancient past.