Mercy Otis Warren (1728-1814) was an American poet, playwright, and activist during the era of the American Revolution (1765-1789). Through her works of political satire, she advocated for the Patriot cause and became acquainted with several revolutionary leaders. In 1805, she published a three-volume comprehensive history of the revolution, considered to be her magnum opus.

A self-educated woman, Warren became a staunch Patriot during the American Revolution, writing three plays and two works of dramatic prose in support of American rights and liberties. Although these works were published anonymously, she still won the attention of many Patriot leaders, whom she often hosted at her Plymouth home. After the United States won its independence, Warren criticized the US Constitution, fearful that it would lead to an oppressive federal government, and denounced the Federalist Party, whom she accused of having betrayed the principles of the Revolution in exchange for power. Her History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution was an important historical work that won her both acclaim and derision.

Early Life

Mercy Otis was born on 25 September 1728 in Barnstable, Massachusetts. She was the third of 13 children born to James Otis Sr. (1702-1778) and his wife Mary Allyne Otis (1702-1774). Her father was a prosperous attorney and politician who won election to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1745, and her mother was a member of an old Massachusetts family, descended from a Mayflower passenger. As a young girl, Mercy Otis dutifully learned the domestic skills that women were expected to know in 18th-century America, such as cooking, sewing, and needlework. But Mercy's ambition and her appetite for knowledge caused her to look beyond the limits of gender roles. When her two elder brothers, James Jr. and Joseph, were sent to the home of Reverend Jonathan Russell to be tutored, Mercy accompanied them, sitting in on their lessons. Mercy was thereby educated in the topics of classical literature and history and was given access to Reverend Russell's extensive library to study other fields. It was unusual for a girl to be given such a broad education in colonial America, but Mercy's academic endeavors seem to have been supported by her father and brothers.

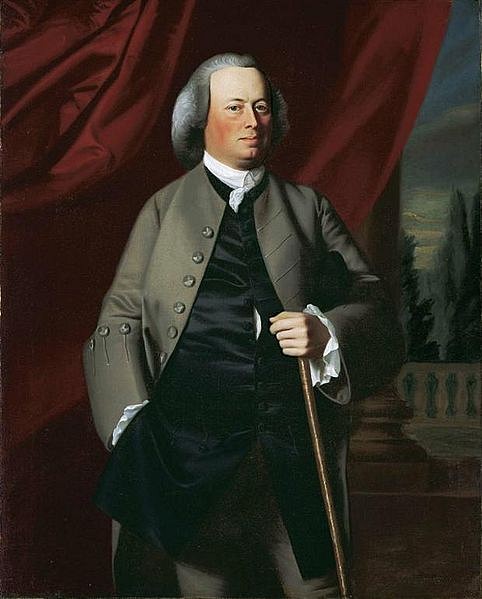

Despite her accumulated wealth of knowledge, Mercy Otis' gender precluded her from being admitted into Harvard, the college that both her elder brothers ultimately attended. Still, she celebrated when James Jr. graduated in 1743; his commencement ceremony at Cambridge may have marked the first time Mercy set foot off Cape Cod. It may also have been the occasion when she first met James Warren, a first-year student at Harvard and a friend of her brother's. Through his friendship with James Otis Jr. and his business dealings with their father, James Warren spent a lot of time with the Otis family over the next several years and became particularly close with Mercy. On 14 November 1754, Mercy married James Warren and moved with him to Plymouth, Massachusetts, where she would live for the rest of her life. By all accounts, theirs was a happy marriage; they rarely argued, and James encouraged Mercy's literary and writing interests, referring to her affectionately as the 'scribbler'. When James' father died, the couple moved onto the Warren family estate of Clifford Farm, where Mercy gave birth to five healthy sons between 1757 and 1766. It was during her second pregnancy in 1759 that Mercy wrote her first known poems.

Rivalry & Revolution

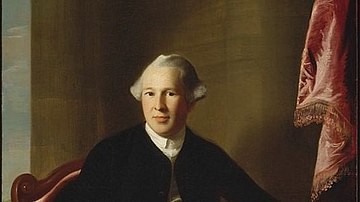

As Mercy Otis Warren was settling into life as a Plymouth wife, her father was rising in the arena of colonial politics. James Otis Sr. had become Speaker of the House of Representatives and had carved out a block of support from amongst the colony's farmers. He was soon regarded as a leader of the colony's populist faction, a position that often put him at odds with Massachusetts Lt. Governor Thomas Hutchinson. A scion of an old Massachusetts family (and a direct descendent of Anne Hutchinson), Thomas Hutchinson was a leader of the colony's Tory faction and represented the established order; indeed, he is often considered the most significant Loyalist in pre-revolutionary America. In 1761, Hutchinson was appointed Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Superior Court instead of Otis Sr., who claimed he had been promised the position by the previous governor. This sparked a bitter feud between the Otis and Hutchinson families, which quickly boiled over into a rift between the populist Whigs and the conservative Tories; the Whigs felt that Otis Sr. had been sidelined so that Hutchinson could increase his personal power and implement Tory policies.

This political rift was only deepened in 1765, when the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act, placing a tax on all paper documents in the colonies. Hutchinson, despite having personal reservations about the act itself, believed in the supremacy of Parliament's authority and announced his intention to uphold the act. Many Whigs opposed the act, arguing that Parliament had no right to directly tax the colonists because the colonists were not represented in Parliament. This argument was loudly championed by James Otis Jr. and his protégé Samuel Adams, who quickly became recognized as two of the leaders of the Patriot movement in Massachusetts. This newfound notoriety led Otis Jr. to become the target of mockery in Tory newspapers. Once, in 1769, he was even beaten up by a royal tax official.

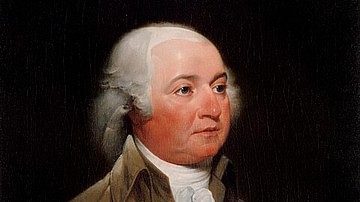

Mercy Otis Warren was enraged at the mistreatment that her brother and father had received at the hands of Hutchinson and the Massachusetts Tories. She was further appalled by the way Parliament was handling the crisis; instead of resolving the issues peacefully, Parliament had sent two regiments of soldiers to occupy Boston in 1768, which only increased tensions and ultimately resulted in the Boston Massacre (5 March 1770). The injustices that both her family and her colony had suffered led Mercy Warren to believe that reconciliation with Britain was impossible, putting her firmly on the Patriot side. She and her husband opened their Plymouth home to Whig politicians and hosted meetings of the Sons of Liberty; in her capacity as hostess, Warren became acquainted with John Adams, Abigail Adams, John Hancock, Patrick Henry, and eventually even George Washington. But it was not enough for Warren to merely act as a salonnière for revolutionary leaders – she wanted a more active role in politics. At the time, politics was considered to be the domain of men, but Warren was not averse to challenging gender roles for a second time. Although her gender prevented her from attaining office or taking up arms, she already had the weapon that she would need: her pen.

Revolutionary Writings

In 1772, a satirical play entitled The Adulator was anonymously published in two installments in the Massachusetts Spy, a Patriot-aligned newspaper. The play centers around an oppressive government led by Rapatio, a selfish and tyrannical despot. Many innocent people have suffered under Rapatio's regime, which is soon challenged by the play's protagonist, Brutus, a brave and noble hero. Brutus urges the people to rebel against Rapatio and his henchmen, telling them to "bring them to account – crush, crush these vipers" (mountvernon.org). In the end, Brutus and the rebels ultimately prevail. It was not difficult for readers to make the comparison to real-life Massachusetts politics; the villainous Rapatio – whose name is derived from the word 'rape' – represented Thomas Hutchinson and other royal officials, while the noble Brutus was based on James Otis Jr. The play proved immensely popular amongst the Patriots, who began to mock Hutchinson by calling him 'Rapatio'.

Despite the anonymity of the play's author, it was not much of a secret that it had been written by Mercy Warren. The popularity of the play led Warren to publish another satire the following year entitled The Defeat; this play again features a villainous character analogous to Hutchinson and ends in his downfall. The play's publication came at a time when Hutchinson was already extremely unpopular, as private letters had recently come to light in which Hutchinson had derided the Patriots' concerns. Warren's plays only served to deepen the resentment against Hutchinson, helping to lead to his removal from office in early 1774; in this way, Warren helped end the career of her father's most hated enemy. Her works also made her one of the preeminent writers of revolutionary ideals. In late 1773, John Adams praised her as "a poetical Genius" who "has no equal that I know of in this Country" (King, 516).

As tensions between Britain and the colonies exploded into the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), Warren continued to publish works in support of the Patriots. She published one more satirical play in 1775 entitled The Group, which was written with advice from John and Abigail Adams, and she wrote two prose dramas called The Blockheads (1776) and The Motley Assembly (1779); these two latter works criticized those Americans who remained loyal to Britain after the Declaration of Independence. In the meantime, Warren continued to host Patriot leaders and officers of the Continental Army in her home. Her husband James had been elected president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, the revolutionary government of Massachusetts, an office he would hold until the body's dissolution in 1780. James Warren also served as Paymaster-General of the Continental Army.

Post-Revolutionary Work

The signing of the Treaty of Paris of 1783 put an end to the war, securing the independence of the United States of America. With the fighting now over, the Americans were left to decide what kind of nation they were going to build. The Articles of Confederation, which had been ratified by the states in 1781, guaranteed a weak central government in order to protect the sovereignty of the states. The Articles, however, soon proved inadequate, and in 1787, a Constitutional Convention was held in Philadelphia to devise a new constitution for the United States.

Like many other revolutionaries, Mercy Warren was skeptical of this new constitution, as she did not like the idea of giving more power to a federal government. In 1787, she wrote several pamphlets opposing the constitution, publishing them under the pen name 'A Columbian Patriot'. In 1788, after the Constitution had been ratified, she attacked it again in a work titled Observations on the New Constitution. Her main argument was that the Constitution lacked explicit protection of the people's liberties; Warren outlined several such liberties that needed to be clearly stated, including freedom of the press, trial by jury, freedom from unwarranted searches and seizures, annual elections, and freedom from military oppression. Many of the liberties that Warren and other Anti-Federalists called for were eventually expressed in the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution that were ratified in 1791.

By the late 1780s, Warren's fierce Anti-Federalism had ruptured her friendship with John and Abigail Adams. John Adams was a leader of the Federalist Party, who believed that a strong central government was necessary for the nation's survival; Warren accused Adams and other Federalists of betraying the principles of the Revolution to enhance their own personal power. When Adams became Vice President in 1789, he declined to appoint Warren's husband or any of her other family to government positions. Warren took this as a personal slight, and the feud between the two former friends worsened.

In the meantime, Warren compiled 18 poems and two new plays in a book entitled Poems, Dramatic and Miscellaneous, which was her first work to be published under her own name. Like her earlier works, these were political and dealt with themes of liberty and virtue, which Warren deemed important for the infant United States to bear in mind. In 1790, she sent a copy to President George Washington, who replied that, although his presidential duties had prevented him from reading the whole book, he was nevertheless "persuaded of its gracious and distinguished reception by the friends of virtue and science" (mountvernon.org).

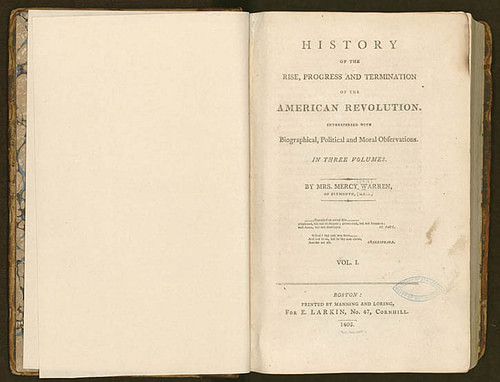

Warren's History of the American Revolution

After the publication of her book of poems and plays, Warren did not publish anything else for the rest of the decade; her writing was hindered both by her declining health and by her grief over the death of her son Winslow, who had been killed fighting Native Americans at the Battle of Wabash River (4 November 1791, also known as St. Clair's Defeat). Still, Warren continued to work on what would prove to be the biggest project of her career: a comprehensive history of the American Revolution. Warren had spent decades researching and writing her history, utilizing her personal connections to obtain relevant letters, reports, and other documents. Finally, in 1805, Warren published a three-volume, 1,300-page work entitled History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution. She was 77 years old at the time of its publication.

The book's historical narrative begins in 1763, at the start of the political troubles between Britain and the colonies. It goes on to cover the major events, battles, and biographies of the Revolutionary period, with the narrative centering around George Washington. Warren does not try to hide her own politics in the book, offering her own opinion on each of the Founding Fathers, most of whom she knew personally. She offers her belief, likely inspired by her Puritan upbringing, that the American Revolution was part of a divine plan to rid the world of tyranny. She also states her view that all history is a constant struggle between virtue and corruption (King, 520). Warren's book does not shy away from the moral issues of the time; she wholeheartedly condemns the institution of slavery, which she decries as incompatible with the Revolution's principles, stating that it could "banish a sense of general liberty" (mountvernon.org). She also criticizes the mistreatment of Native Americans during the Revolution. The narrative continues on past the war, covering the Constitutional Convention and the presidency of George Washington; here, Warren criticizes Washington for appointing John Jay as both the Chief Justice of the United States and US Secretary of State simultaneously, a dual role that she claims gave Jay too much power. Warren also denounces many policies of the Federalist Party.

The work, which is often considered Warren's magnum opus, was one of the first comprehensive histories of the revolution, and the first to be written by a woman. It was also unique for having been written from an Anti-Federalist perspective, at a time when most works about the American Revolution were being written from the Federalist point of view. Indeed, Warren was by now committed to the Democratic-Republican Party (also called the Jeffersonian Democrats); President Thomas Jefferson liked the book so much that he ordered each member of his cabinet to buy a copy. The book, predictably, fared less well amongst Federalists; while Warren was usually favorable towards George Washington, she sometimes criticized him, which Federalists felt to be unacceptable so soon after his death. John Adams, of course, was incensed by his treatment in the work; in 1807, he published a series of ten letters denouncing Warren's research ability and skills as a historian, going so far as to assert that "history is not the province of the ladies" (King, 529). Warren, appalled by Adams' behavior, stopped communicating with him until the pair reconciled in 1813.

Death & Legacy

On 19 October 1814, Mercy Otis Warren died at the age of 86. She was buried at Burial Hill in Plymouth beside her husband James, who had predeceased her by six years. Her legacy is an important one. She was well-educated and politically active at a time when both qualities were discouraged in women. She was one of the most influential propagandists and writers of the American Revolution, whose work helped shape the common perception of Patriot ideals, and whose later work helped lead to the Bill of Rights. Her comprehensive history was one of the first to be written about the Revolution and did not refrain from making controversial, yet important, observations, such as her criticisms of slavery, Federalists, and aspects of Washington's presidency. Warren's memory persists, therefore, as an important figure who helped shape the story of the United States in the era of the early republic.